Gender Studies placement student Grace’s second blog look at intersectionality in the GWL collections.

Since beginning my Masters in Gender Studies I have repeatedly learnt not to be surprised when ideas I considered to be part of modern feminism show up throughout documentation of the past. One of the first things we discussed in class was the importance of intersectional feminism. As such a vital concept in feminist activism it makes sense that there has always been an awareness of its importance among feminist groups including Lespop. While reading through the files it became clear that they considered an intersectional approach essential, often offering classes focu sing on the specific needs of black women and women with disabilities.

sing on the specific needs of black women and women with disabilities.

First coined in 1989 by civil rights lawyer Kimberlee Crenshaw, intersectionality describes an awareness of the different ways in which oppressions can overlap. In her writings she focusses on the idea that the specific needs of black women were often ignored by anti-racist and feminist groups as the dominant identities of black men, and white women took prominence. She introduced a framework through which this can understood and provided a language for something that many black feminists, and other minority groups had long been aware of.

It struck me that Lespop existed 5 years before this term was coined and yet still placed the idea as central to their organising. This taught me an important lesson in considering early action. While there is no denying that Crenshaw is an inspirational and trailblazing activist, there have been people living under ideas for years before they were first named in academia. It is surely no accident that these theories were lived by lesbian and black feminists even before they were named and a deeper look into the GWL Lesbian Archives shows that Lespop was not the only group this applied to.

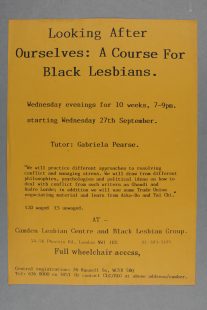

The Camden Lesbian Centre and Black Lesbian Group existed at a similar time to Lespop and emphasises the necessity of intersectionality perfectly. Black lesbians existed within intersecting oppressions relating to race, gender, sexuality and often class, as shown by a poster with the words:

‘Black Lesbian Struggle is Black

Black Lesbian Struggle is Lesbian

Black Lesbian Struggle is Working Class

Black Lesbian Struggle is Women

Black Lesbian Struggle is International

The experiences that join us are thicker than the water that divides us.’

In the 80s Black was largely used as a cover-all term for those of Afro-Caribbean and South Asian descent. Immigration from commonwealth countries in these areas meant that Britain was becoming a more racially diverse country across the second half of the 20th century and the prevalence of race as an issue in British society placed black lesbians in a particularly precarious place. Both the Black Lesbian Group and Lespop focussed on the difficulties of existing in a racist and homophobic society, Lespop briefing papers show the dedicated effort to ensure their volunteers were diverse, as well as offering specific advice to those who would be targeted by the police for both their sexuality and skin colour.

The existence of these groups shows that there was an awareness that mainstream gay activism was predominately white, male and able bodied which meant that the issues that affected lesbians, black lesbians, or lesbians with disabilities were side-lined. An intersectional approach shows that these differing oppressions cannot be separated out and therefor activism that seeks to help LGBTQ+ people must consider them. The Black Lesbian Group and Lespop’s focus on racial issues, as well as Lespop’s awareness of accessibility issues for lesbians with disabilities shows that while intersectionality would not be named for half a decade the theory behind it was a lived reality for many. This taught me the important lesson that I should be aware of whose activism is lost by using modern language to interpret actions of the past. Intersectionality might not have been named, but it was certainly present in the lives of these activists.

Comments are closed.