Rebecca Close is a doctoral researcher at Aalto University doing a dissertation in artistic research as ‘reproductive work’. Rebecca conducted research on the Sappho Archive held at GWL in 2022 and wrote this piece on Sappho, queer networks and assisted reproduction.

The recent overturning of Roe Vs. Wade shot reproductive politics into the mainstream media in an unprecedented way. As well as the legal effects of the Supreme Court decision, the communication leading up to the legislation change, including the supposed unintentional leak, was a shocking jolt to the public imagination. The speed at which one can be updated with regards to changes or proposed changes to one’s access to reproductive resources and rights makes the transmission of information a key tool for managing not only the reproductive practices addressed by a given law but our energy, focus and attention. In this post I consider the news as a key technique of reproductive control, and ask whether the notion of the queer network can be reassembled after the packet-switching networking of the internet.

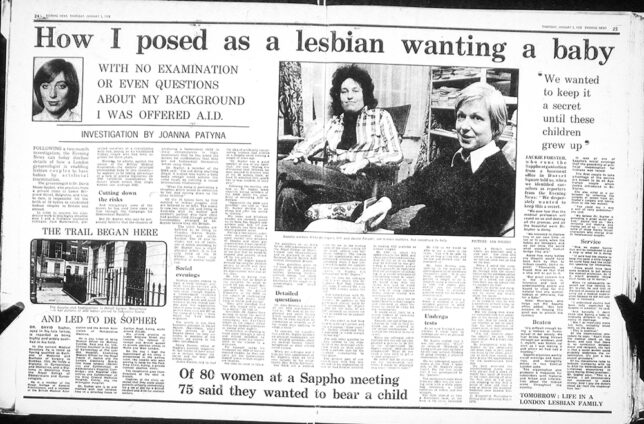

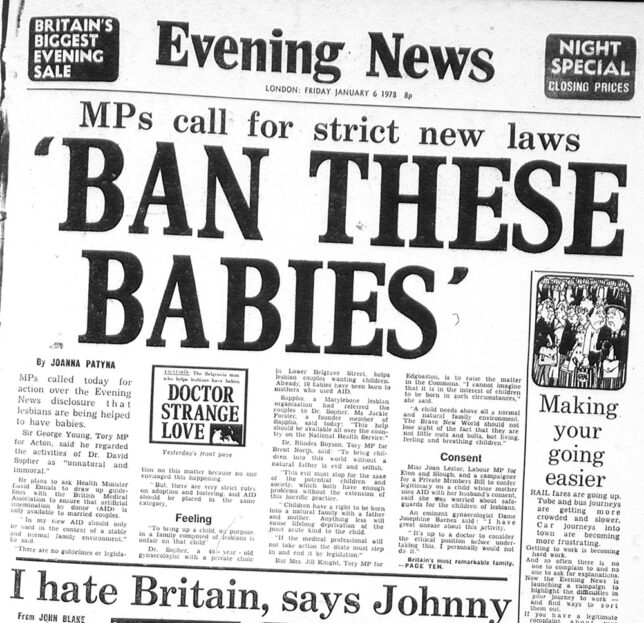

As part of my doctoral research on queer reproductive work I have been researching Sappho, a lesbian arts, poetry and politics magazine that ran between 1974-1981. Sappho had a circulation in the UK of around 900 readers but was shot abruptly into the mainstream media in 1978 when the London Evening News printed an exposé on how the editors were connecting their readers with doctors willing to perform artificial insemination by donor (a practice referred to at the time with the acronym A.I.D). The historian Rebecca Jennings (2017) offers a complete chronicle of the Evening News v. Sappho case, but I wanted to check out the whole run of the magazine, currently held in the collections at the Glasgow Women’s Library, to understand how an arts and poetry magazine came to run a proto-queer proto-fertility clinic.

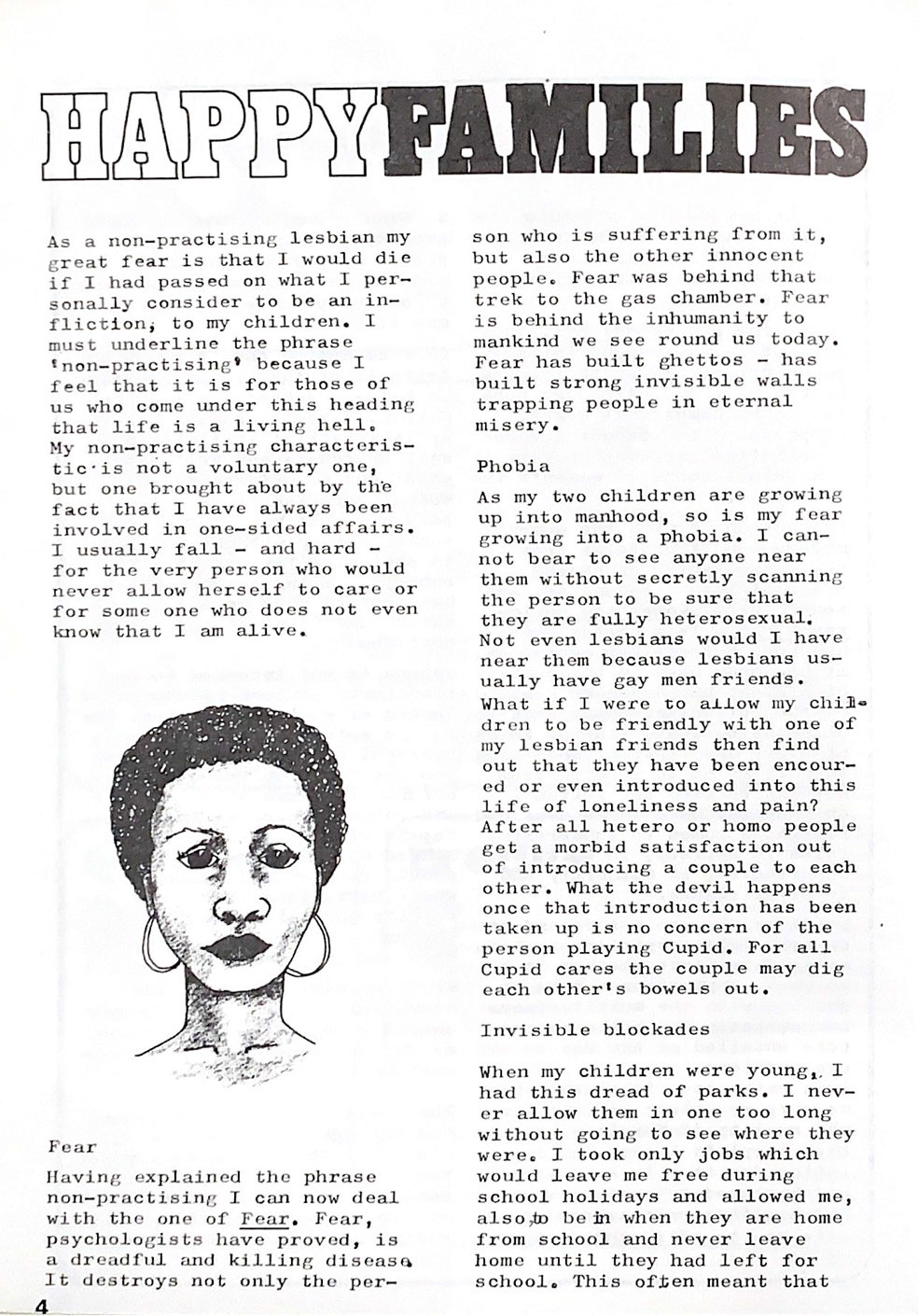

Image: Bella Ashbey, Happy Families column, Sappho, Volume 1 Issue 7 (1974) and Rosey, ‘A Day in the Life of A Farmer’, Sappho, Volume 5 Issue 5 (1977).

Sappho regularly covered the topics of fostering and artificial insemination, publishing medical research and updating readers with regards to changing laws and regulations. They also ran a column called Happy Families that shared experiences of and advice on parenting and queer domestic life. I was surprised how the topic of queer parenting was consistently situated among a lively ecology of wider reproductive politics issues. Sappho ran a ‘day in the life of’ column written by readers about their working days, offering a sparkling archive of experiences of labour activities in the 1970s. They published original manifestos and documented activism on the intersection of lesbian identities and sex worker and trans rights.[1] Sappho were involved in the 1978 Child Benefit Lobby – a meeting attended by a coalition of British women of color and migrant mothers at the House of Commons to protest the proposed withdrawal of child benefits from families who had experiences of migrating to Britain. Sappho later published the statements of the many lesbian mothers present at the meeting.[2] Over the decade Sappho established many activist groups, including, in 1975, supporting Sappho readers to set up a meeting space to discuss lesbianism and disability.[3]

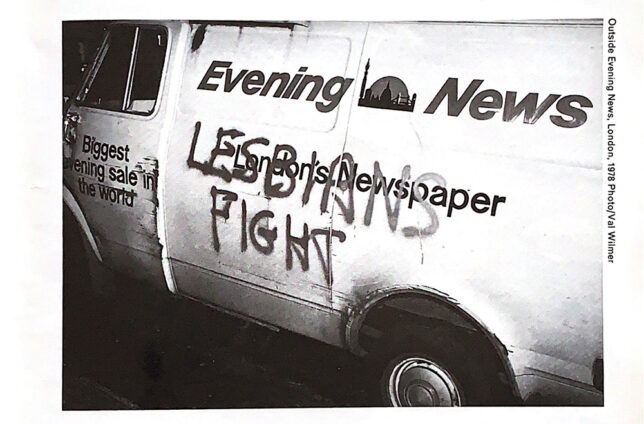

Sappho also connected readers to arts, theatre and poetry projects: in June 1975 they published a call from Gay Sweatshop Theatre looking for plays, and a year later Sappho readers and team contributed research to Care and Control (1976), a play focusing on custody battles and legal discrimination experienced by lesbian mothers. Sappho published reviews, poetry, short stories and drawings, a few of which were signed by ‘Member of Wages Due Lesbians’, another prominent international network of collectives active in struggles related to sexuality, disability and race. It was this network of art and activist collectives that showed up outside the London Evening News offices on the 9th January, 1978, to support Sappho’s protest against the homophobic exposé.

Across studies of reproduction it is common to foreground histories of IVF, citing the first test-tube baby case, Louise Brown, who was coincidentally born the same year as this expose in 1978, as the birth of the fertility clinic. What if these queer, crip and antiracist networks are the real origin story of the ‘new reproductive technologies’?

Post-internet is a contentious term used by art critics to refer to practices that reflect on the impact of the internet on society, first coined in 2006. I like the definition used by curator Karen Archey (2014), who defines the ‘post-internet’ as:

‘an internet state of mind – to think in the fashion of the network…an art object created with a consciousness of the networks within which it exists.’

Sappho magazine, although existing before the internet, might be considered ‘post-internet’ to the extent that it had at the centre of its politics and production the maintenance of networks: networks of activism, art production and family. The term ‘network’ suits the ‘Sappho families’ well if one is guided by early 20th century British social anthropologists, who began using the term to designate the more flexible kinship formations they were observing that were not necessarily organised around the structural institution of marriage.

In 1978, and over five days, the Evening News disassembled and simplified the networked dimension of Sappho into a few discrete headline topics: ‘Ban these babies’ and ‘Doctor Strangelove’. Such sensationalism fuelled MPs and the British Medical Association, quoted in the articles, in their conservative lobbying efforts to regulate queer access to artificial insemination. The pathologisation of lesbians as unsuitable parents in exposes such as this directly impacted the 1990 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, particularly the so-called ‘welfare clause’ that stipulated that clinicians consider ‘the need for a father of any potential child’ before offering women fertility treatment. This requirement was not removed until 2008 and constitutes a major chapter in the history of reproductive control in Britain.

This should not be understood, however, as an isolated instance of homophobic media or medicine. Rather, debates around family, parenting, the body and reproductive technologies are assembled in order to police access to material resources (housing, benefits and work) as well as survey and control the public’s imagination regarding what forms of social reproduction are possible. For theorists of racial capital, this policing of material resources and the imagination –particularly the control over who can be recognised legally and normatively as parent, national and worker– fundamentally defines the paranoid ‘racial sensibility of Western civilisation’ (Robinson, 1983, p.2). Such mediatised scandals are not just homophobic but inherently racist and ablest because they evidence the structural control over social and biological reproduction as a site of capital extraction.

The news’ binary logic of expose and censorship involved the reduction of queer reproductive work to a few consumable headlines: ‘Doctor Strangelove’ and ‘Ban these babies’. The loss of the memory of the coalitional dimension of queer reproduction struggles is intensified in today’s networked society, where simplification and abstraction occurs in less than a second. This can be best elaborated on in relation to the Internet itself: a networked technology defined fundamentally by the drive towards the simplification and abstraction of data.

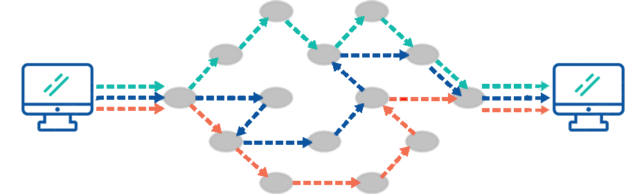

Unlike the uninterrupted data streams of both electronic communications and broadcast technology, the Internet uses packet-switched networking, which breaks a given message down into discrete parcels to be sent along different routes at different times. Only on arrival and with the storage, routing, and processing power of a computer is the data reassembled. Along the way, many technologies and protocols work on the information to break it up. Each successive, higher layer abstracts the raw data a little bit more, making it simpler to read for applications and users. While networking is often discussed in topological terms, emphasizing horizontal exchange between hosts, actually its implementation is layered vertically. The drive towards simplicity has consequences for the reassembled message: sometimes a parcel or entire layers of complexity get lost.

In other words, the meaning of the term ‘network’, which is still used across many academic fields of research to describe horizontal kinship formations, changes fundamentally with and after the internet. Far from horizontal, the networked technology of the internet stacks vertically in ways that simplify and abstract. This is the reproductive politics of the network and the body politics of packet-switching.

At some point during this research I looked into the biography of Sappho’s editor, Jackie Forster, whose papers are also held at the GWL. It didn’t occur to me to do this before as I find psychobiography one of the least helpful research tools. Yet reading that Forster lived with her partner and her partner’s kids made me consider how one’s family life has a major impact on one’s work and vice versa. Living with and spending time with my partner’s daughter over the last decade has fundamentally impacted the way I think about the organisation of housing, work, family, art and research. Recently, more attention is being paid to labour activities involved in maintaining LGBTQIA+ life (Raha, 2018; Wesling, 2015), from creating homes to art making, which Douglas Crimp called ‘cultural activism’ (1987). These theoretical frameworks help one to understand how all home life is organised structurally by the pressures of capitalist production, and how one is often aware of these pressures especially as alternatives are nurtured and pursued.

Perhaps I was surprised to find so much evidence of interconnected queer, crip and antiracist struggles across the pages of Sappho, because of the resonances that ‘the Sapphic’ has in the UK in the 2020s. There is a geopolitics of ‘Sappho’, as there is of the term ‘lesbian’, which contains the name of a Greek island in its etymology (Parmar, 1994). The uptake of these Greek words in the English language cannot be too far separated from the racialised reading of the Mediterranean region and the association of aspects of ancient Greek culture with Euroamerican whiteness (Robinson, 1984). These Eurocentric legacies have tended to block the occupation of the Sapphic as a site of antiracist and class struggle. This was Cherrie Moraga’s conclusion when the author commented to Amber Hollibaugh in 1981: ‘if you have enough money and privilege, you can separate yourself from heterosexist oppression, you can be Sapphic or something, but you don’t have to be queer’. Since then queer too has been subjected to the abstracting effects of the stacked technologies and protocols of neoliberal consumer culture.

Today print media’s binary logic of expose/censorship has given way to constant streams of data and hourly news updates: how to reassemble the coalitional dimension of the network after the packet-switching networking of the internet?

Networks of Care & Critique is a piece of drawing software that I developed while doing this research: an invitation to enact the pleasures of remembering, without idealising, the networks of care and critique that maintain your home and work life. It was first exhibited in the creative coding exhibition ‘The Love Ethic’ and can be accessed directly here.

*Thank you to everyone at GWL.

Footnotes

[1]See: Susan Lewis and Ben Foreman, ‘Transexual Liberation Manifesto’, Sappho, Vol.3.Iss.7. (1974); ‘Lesbianism and Prostitution’, Sappho, Vol.5.Iss.8 (1977).

[2] Child Benefit Lobby, Sappho, Vol.6.Iss.6. (1978).

[3] E.B, K.B and J.C, ‘Disabled Gay Women Group’, Sappho, Vol. 4, Iss. 11 (1975).

Works referenced

Archey, K. (2014) Art Post-Internet, exh.cat, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art: Beijing. http://www.karenarchey.com/artpostinternet

Crimp, D. (1987) ‘AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism.’ October, Vol. 43, (Winter, 1987), pp. 3-16.

Hollibaugh, A. and Moraga, C. (1981) ‘What we’re rolling around in Bed with: Sexual Silences in Feminism: A Conversation towards ending them’, https://www.freedomarchives.org/Documents/Finder/DOC46_scans/46.WhatwereRollinAroundinBedWith.pdf

Jennings, R. (2017) ‘Lesbian Motherhood and the Artificial Insemination by Donor Scandal of 1978’. 20 century British history, 28(4), 570–594, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwx013

Parmar, P. (Director) (1991) Khush [film]. Kali Films.

Posner, J. (1982) Spray It Loud. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Raha, N. (2018) Queer Capital: Marxism in Queer Theory and Post-1950 Poetics. PhD Dissertation. Sussex University.

Robinson, C. (1983, 2000) Black Marxism, The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. London: Zed Press.

Wesling, M. (2012) ‘Queer Value.’ GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies (Vol.18, No. 1), pp. 107-126.

Comments are closed.