Anabel recommends:

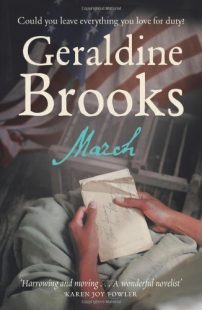

March by Geraldine Brooks

March was recently recommended at the Library’s monthly Book Picnic by Elaine, who kindly donated it to stock. I have also read it and loved it, so I thought I’d tell you why in case you might love it too.

March is the father in Louisa M Alcott’s Little Women, who is away as a chaplain with the Union Army in the Civil War. Geraldine Brooks’ novel imagines what was happening to him while his wife and daughters were left at home. He is based on Alcott’s own father and other real-life characters also have cameo roles, though only abolitionist John Brown is crucial to the plot. I had not heard of Brooks before, so had no idea what her writing would be like – I discovered later that she is a former foreign correspondent and that this, only her second novel, won the Pulitzer Prize. My expectations were ratcheted up, and I was not disappointed.

March tells the story of an idealist who goes off to war for what he believes is a just cause. As you might expect, his experiences reshape both his ideas about the world and his relationships with his family and he returns home a changed, almost broken, man. I really liked the structure Brooks used to portray this. In the opening chapter, March is writing to his wife, but finding it impossible to tell her about the realities of war. The army has just made a disastrous retreat across a river with many men drowning. March, hoping to comfort the survivors, goes off to look for the field hospital on an old plantation where one remaining enslaved woman is helping the surgeon. He realises when he approaches the house that he has been there before.

We then skip back twenty years to learn why March knows the place. When little more than a boy, trying to make a living as a Yankee pedlar, he arrives at the house to sell his trinkets, but the fact that he also has books attracts the Master, Mr Clement, and he is asked to stay for a while. March finds it hard to reconcile Clement’s general air of culture with his attitude to the people he is enslaving. One of them, Grace, can read, but another is very angry when March tries to teach her daughter, as it is now against the law for enslaved people to learn to read. The child is very bright so Grace brings her to him for secret lessons. An attraction develops between March and Grace and he can’t resist kissing her. However, the lessons are discovered and he is expelled, but not before witnessing the savage beating administered to Grace.

From here, alternate chapters relate March’s Civil War experiences, in which Grace appears and disappears – she is, of course, the enslaved woman in the field hospital – and the story of his previous life with his wife and growing family. When both stories are brought up to date they collide – March takes seriously ill and his wife, Marmee, travels south to visit him. At this point her voice takes over for a while, we see some of the events we have already read about from her point of view and she learns of the many things about her husband that he has kept from her – both the hardships of the war and events in his past. She feels bitter, but when trying to write to her daughters about their father’s condition she realises that she is self-censoring in the same way. As for March, he has to accept that he is not the same man and the ghosts of the past will continue to haunt him.

There are a lot of interesting themes here, not least that of the Civil War itself. Both March and Marmee are passionate abolitionists who help people escaping slavery through the “underground railroad” to Canada. It’s a mistake, though, to take the simplistic view that all in the Union camp were similarly enlightened.

How does the Little Women theme hold up? Occasionally, both characters refer to their daughters as their “little women”, but I think you could read March without even noticing that it is based on another book. It’s years since I read Little Women so I’m not sure how much, other than the names of the characters and the general idea, is carried over anyway. Certainly, my memory is of fine, upstanding, righteous people, whereas this March is more human and very flawed. We know from Marmee’s chapters that he totally misunderstands his wife in crucial areas and my feeling is that it is she who is going to get their relationship back on track at the end.

This is a gripping, powerful book. Reading it, I was impressed with the depth of Brooks’ research and how lightly it was carried – though complex, it was easy to follow and to remember the many and varied characters.

Comments are closed.