by Ioulia Kolovou

They fear the forest but that is where I feel most free. With my bow and arrow I hunt and the furtive animals know me. There are no judging eyes, no scrutiny, no frown of disapproval at my male attire. The force of my arm is indisputable. The string of the bow bends at my command. I can dispense death as well as any man.

In the forest, in the great cathedral of tall barks and green canopies, amid the whispering of branch and twig and leaf, I am bathed in light, I am told all the secrets. The fawn and the fox know me well. Even with the bow in my hand, the stiff arrows in the quiver, the seamless synch of hand and eye, and the bowstring singing its ancient song, I am not the enemy. Here in the forest we are all part of the round dance of life and death.

I am happy here. Neither boy nor girl, just I, the forest keeper’s child. I know my father sees in me another child, a phantom one, the son he had desired. Still he loves me and teaches me everything he has been taught himself. I learn to conquer even the darkest powers of the forest; the perfidy of the snake, the hunger of the wolf. He teaches me how to set up snares and make arrows and hit marks. My father and I in our secret kingdom, we love one another; not only as father and daughter, not even as father and son, but as instructor and instructed. The keeper of the secrets needs to pass them on before death seals his lips forever. I will continue his legacy. He will not have lived in vain.

On the day my father dies, I consider running away and hiding in the forest, vanishing once and for all from the face of the inhabited world. But I cannot. I am not the heir to his kingdom, after all. I have now become a mere girl, banished back to the world of women. The thing is, women owe me no loyalty, as I have not shown any loyalty to them so far. Unless I become one of them, unless I share the symbols of their slavery – the dress, the distaff – and give up the guardians of my own freedom, the male clothes, the bow and arrows. They will embrace me enslaved, not free.

I become a girl and I pay the full price. Instead of the paths and secret ways of the forest, I earn the confinement of a small house where you can touch the walls end to end if you spread your arms wide. Instead of the great cathedral of green and golden light, the low roof where mice pattered at night. Instead of the hooting of the owl and the keening of the fox, the grunts and groans of her new husband as he takes his pleasure of her, and her weak whimpering, and the mewling of their babies, which fall to my lot to look after.

It is so easy to become enslaved. My soul screams for freedom but my body forgets. It gets used to sitting demurely, knees drawn together, hands folded over the apron. My head quickly learns to bow over the needlework, my neck exposed, as it is fitting to an animal of yoke. Restrained movements imposed by dress and apron. The apron strings my bondage. Small steps, fear to tread outside the threshold of the house. I, who was the hunter in the forest, now a prisoner in a house.

In my dreams I don the old clothes, the boy’s clothes, and I stride through the forest, I climb trees, I jump into pools and streams. I am the master of my movements and my inclinations. When I wake up a slave again, it seems to me that I was alive in the night, a spirit liberated from the underworld for a short time, but now I have to return to the dark abode, bound by invisible, unbreakable chains.

I have forgotten my father’s face. Death has wiped out his features, and I can only remember his tall outline framed against the doorway, as he was the last time he had returned home, never to walk out alive again. Then I dream of the two of us walking in the woods; it is the old times, when I was still small and we were still happy. He is far ahead of me, and at some point he turns towards me and I hear his voice in the distance: “You are better than any boy a father might wish for”. And then he dissolves, and I am left alone, carrying his bow and quiver, my face bathed in tears. The tears follow me from the world of dreams to the world of waking. But they are dried by the fire of anger that has begun to simmer inside me.

Twice I was transformed. They say – I don’t know, I can’t remember – that once upon a time I was a man. Then a piece of flesh was cut off from me. They say this is where all my strength was ensconced, and when it was nipped off it left an open wound at its place. See, they said, it’s an open wound still, it bleeds every month; a vivid red river that quickly turns into rust. It scares me, and they fear it too. This is your weakness, this is the remembrance of your mutilation, they say with voices spiked with loathing and envy, for they too remember my power. Your curse will never go away except, when you are very old and then it won’t matter anymore, for an old woman and an old man are equally useless, unwanted flesh.

You were born transformed, they tell me, fallen from the grace of being a man. Your wound is there to prove it. Yet, touching it gently with my fingers, this wound spreads sweet warmth and then explodes into a joy so deep that I want to laugh, so intense that I want to cry. What kind of wound is this that gives pleasure instead of pain? Wicked, they shriek, it is wicked to touch it. As for the pain, it will come, oh, rest assured, there will be much pain in store for you. Just so you remember what you are, and what you cannot be.

My mother dies. Have you seen an old weather-beaten ox or horse lie down with foam at the end of its mouth, dry lips drawn to reveal a few remaining yellow teeth? Have you thought, the dumb animal is smiling, sensing that this is the end of its troubles, that there will be no more plodding, no more lashing on the bony back, no more kicks or iron spurs? This is my mother dying, serene and smiling in death as she never was in life. He buries her, and her young children weep because everyone else is weeping. But I am not. I stand over her grave and glare at everyone.

Perhaps I should have wept more bitterly than everyone else. Not for the past but for the future. Only a few hours later, when she is lying still warm in her grave, her first night of freedom, that man, my stepfather, pushes me into the bed and says, I need a woman and now you are the woman in the house.

I am subjected to the cruellest torture. The pain is all that they promised me, and worse. I bite my lips until they bleed. But no cry escapes me. I won’t give him that pleasure, too, the mark of my humiliation.

Death can only save me from this, as it saved my mother. But not in the same way.

It takes me a long time to collect all the dry twigs and pine needles I need, and to prepare all those bits of char-cloth. I bide my time. Then on a night of howling winds I get out of his bed – he is snoring like a big fat pig – and I do what I have to do. Dry fuel on every surface in the cottage and the pigsty. The barn will take care of itself. The fire will be burning for days. I make sure of that.

I run down the hill, invisible, naked, the way I came out of my mother’s womb. The little barge is well hidden among the reeds, with the leather boots and my late father’s jerkin and britches and bow and arrows. I dress myself anew. The barge glides on the muddy waters, the current so strong that I barely need to steer. The river takes me away. The girl Jehanne will never be seen walking the earth again. The girl Jehanne is dead.

The force of my arm is indisputable. I can dispense death as well as any man.

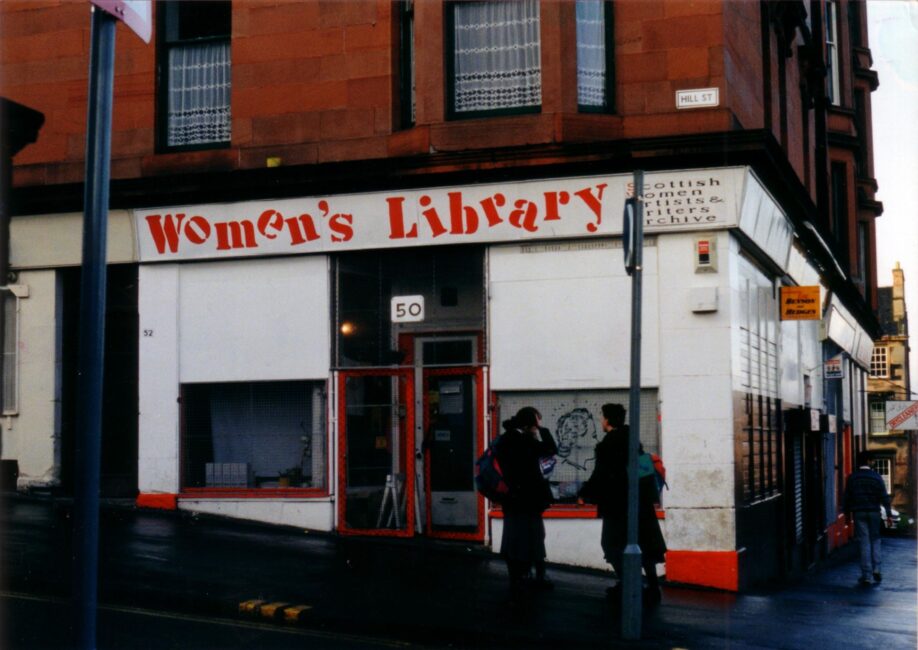

This short story is an extract from my historical novel set in the period of the ‘First Crusade’ (1096-1099). I had conceived the character of Jehan(ne), a female cross-dressing medieval crusader, before visiting the Glasgow Women’s Library, but a number of items in the GWL inspired and helped me to visualize Jehan(ne) more clearly: her story was the story of many women who decided to cross the boundaries of biological ‘predestination’ and to re-create their gender according to their own precepts. ‘Amazons and Military Maids: Women Who Dresses as Men in the Pursuit of Life, Liberty, and Happiness’, by Julie Wheelwright, (London: Rivers Oram Press/Pandora List, 1989) is a well-researched account of cross-dressing women warriors in history. I also drew inspiration from a great number of articles, poems, stories, and letters, published and unpublished, in the fascinating GWL archive of ‘Spare Rib’ magazine, exploring the subtleties of sexual identity and the formation of self.

Ioulia Kolovou studied History, Classics and Linguistics in Greece and Argentina and holds an MSc in Creative Writing with Distinction from the University of Edinburgh. Historical fiction and fantasy, historical gender and sexuality are a part of her research.