The idea of knitting up patterns to add to our museum collection was something that had been floated back when I started volunteering for GWL in early 2019. No pattern had really jumped out at me, though. If I was translating a written pattern into a physical object – something to be shared with others – it felt important that it should say something about women and craft. Over the years I’ve knitted several vintage patterns for myself but for that it’s enough that they just be attractive. This pattern needed to be something more.

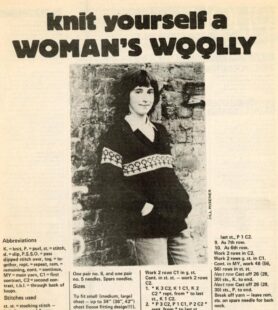

That pattern is the Woman’s Woolly, a 1982 pull-out from the feminist magazine Spare Rib.1 Our copy was donated to us by Shirley Henderson and she talks beautifully about the place of knitting and women’s magazines in her life in her own blog post, Spare Ribbing: Unpicking the Woman’s Woolly. This one, more than any other single pattern in our collection, doesn’t just say something about women and craft: it bellows it. Initially, I thought this would be a quick blog post about the choices I made in making this jumper, just my musings on knitting it up. Turns out, that’s Part 2. First though, there’s a whole lot more going on in the two pages of pattern than just the instructions.

As you’ve taken the time to read this far, you’re probably a little interested in knitting. But many others won’t. Maybe there’s a belief somewhere in the back of their minds that a focus on handcrafts weakens feminism, reinforces ideas around women and the home when really we should be smashing our way out of that box. It’s not a new tension, as textile researcher Dr Alison Mayne explores in her article Stitchy Fingers: Making By Hand In The First Decade Of ‘Spare Rib’, the anticapitalist desires of the 1970s for self-sufficiency butted uncomfortably up against a second-wave feminism that sought to liberate women from domesticity. Maybe sewing your own clothes is “a way to engage in the radical act of demonstrating alternative lifestyles”2 or maybe it’s just your mother’s dressmaking in modern prints – that was the dilemma the 1970s editors faced.

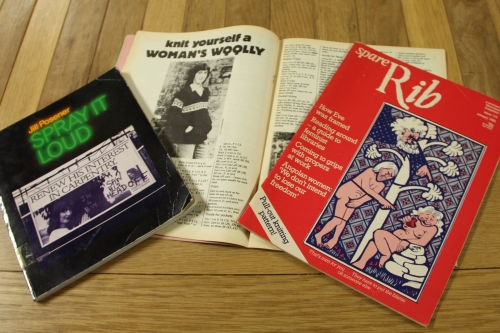

This is the last knitting pattern Spare Rib published and, although it was part of the first edition of 1982, there’s still a definite late 70s feel to the Woman’s Woolly. I’ve worked with quite a lot of vintage patterns that GWL holds and, one of the things I’ve learnt is that older patterns often lack clear dates. You quickly learn to date them by the photos and styling. With this pattern, those pictures tell a story all of their own.

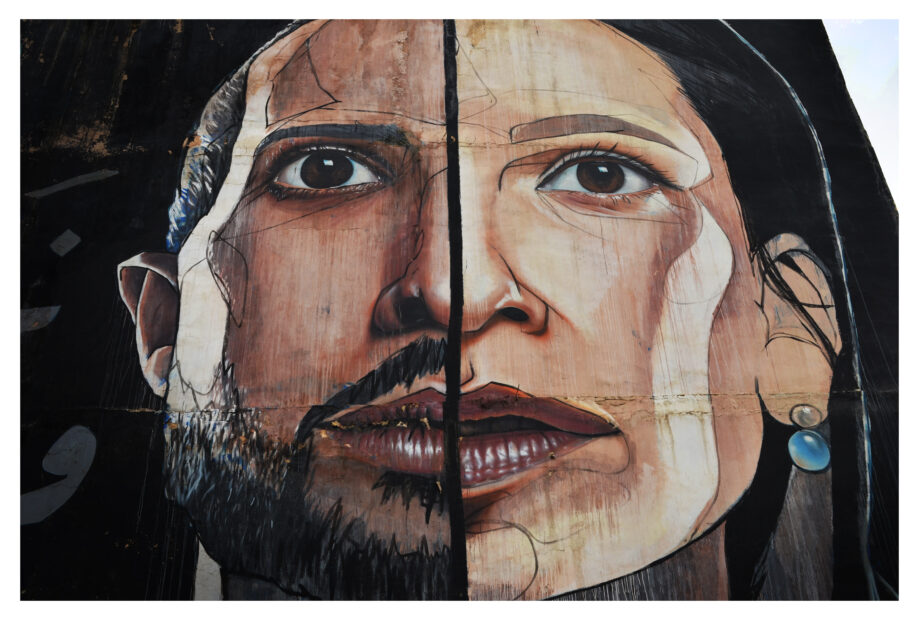

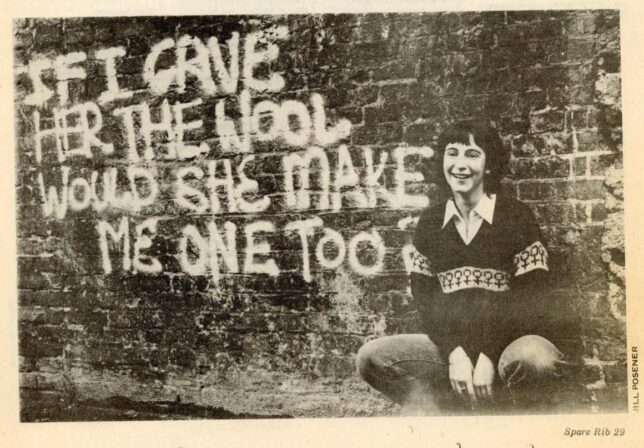

The images were taken by playwright and photographer Jill Posener (her work is currently part of the Tate exhibition on women’s activist art in the 70s and 80s). Later in her career, she would edit Nothing But The Girl with Susie Bright, a collection of lesbian errotic photographs and biographies, which today you can’t buy for under three figures (believe me, I’ve looked). But in 1981 she was working on Spray It Loud, a photographic collection of radical and political graffiti. She took the famous image of the Fiat billboard “If it were a lady, it would get its bottom pinched” with the words “If this lady was a car she’d run you down” spray painted underneath. It’s actually the first image of the chapter in Spray It Loud on women’s graffiti and she thanks Spare Rib in the book’s acknowledgements.3

This says to me that the choice to photograph the jumper in front of a piece of graffiti – in this case reading “If I gave her the wool would she make me one too?” – is obviously inspired by her work at the time. It’s also the punchline to a very old joke in queer circles, extinct by the time I came out, which begins “My mother made me a homosexual.”4 In this one image, it’s subverting the domesticity of knitting, joking with queer women in the know, referencing bigger trends in political street art and illustrating how your finished garment is supposed to look.

I suspect most of the women involved with this jumper and photoshoot would baulk at the idea that I’m about to talk about their clothing choices as ‘fashion’. In her post Lesbian Feminist Dress Codes, fashion historian Eleanor Medhurst (aka Dressing Dykes) makes a similar point when talking about what became the uniform of a particular group of feminists of the 70s and 80s. They attempted to opt out of fashion entirely, by embracing the opposite of everything they were supposed to wear as women and becoming so ‘ugly’ that they would free themselves from the male gaze.5 The problem with that approach is that there is no opting out: whatever you wear says something, whether you intend it to or not. Although there was never any explicitly stated dress code for second-wave feminism, one emerged nonetheless,6 a style of dress that communicated your politics to those around you and called to your tribe: “I’m one of you!” In rejecting fashion, they made a fashion all of their own.

So why am I taking time to talk about fashion? Because the model for the jumper is wearing it and, I’d argue, wearing the uniform of late 1970s lesbian feminists. Yes, this pattern was made and photographed in 1981 but fashion – and especially anti-fashion – doesn’t get revamped for the new decade at midnight on the 31st of December. Skipping over the jumper for now (I’ll come back to it in Part 2, I promise), let’s focus on the model and what she’s wearing. Even in a black and white picture, we can make a few assumptions. She’s wearing blue jeans and a wide collared white shirt with short, shaggy dark hair. And what she isn’t wearing matters too: little to no makeup and minimal jewellery. This simple androgyny was the feminist – and more specifically lesbian feminist – uniform of the late 1970s.7

One thing the photographs don’t show us are the bottom of her jeans or her footwear. Boots were often the preferred form of sensible footwear but trainers weren’t uncommon either – practical and explicitly unfeminine, like the rest of the uniform. Jeans in the 50s and 60s, including on women, had been rebellious and countercultural but, by the late 70s and early 80s, they’d become so widespread as to have lost their teeth.8 As something everyone wore, they were invisible, and therefore not ‘fashion’. Even within jeans though, there are trends and – without being able to see more of the model’s ones – it’s hard to know if these adhere to any of them. But I can make a few inferences from the pictures. She can crouch in them so they’re probably not cut tighter around the hips and bum specifically for women – lycra was only just starting to be incorporated into denim and even then it was mostly reserved for high fashion, not street-level feminists.9 They’re most likely a pair of Levi’s or Wranglers, unisex, bootcut or straight-leg. Even from the black and white photo, you can see that they’re a lot paler than the jumper, closer to the shirt. Dark indigo denim had slipped out of favour, replaced by lighter shades of blue – even when trying to avoid fashion, feminists were still at its whims, whether they realised it or not.

I’ll be honest with you, I spent significantly more time than it warranted reading up on the shirt. It’s a wide collar – much wider than anything you’d find in the 21st century – and one of the things that for me says Seventies about these photos, even though they’re from 1981. Everything I found told me that collar points got really long in the 60s and 70s but none of them could tell me why. Which means, I now get to give you my best guess from what I know, which is this: Menswear underwent the biggest experimentation with colour and shape since the 18th century – sometimes known as the Peacock Revolution – and began to redefine what masculinity was in clothing. At the same time, women were increasingly co-opting and wearing clothing designed for men for comfort, practicality and politics. Women’s collars got big because men’s got big and a wide collared shirt became a unisex fashion item. Like the jeans, our model is dressed in a shirt that, by this point, has lost many of its connotations of gender.

Even before I’ve cast on (i.e., started knitting), the images that accompany the pattern itself are telling a story of feminist resistance, feminist art, feminist fashion and feminist creativity. Unfortunately, the same can’t necessarily be said for the jumper itself. But that’s Part 2.

- Luknitics. ‘Knit Yourself a WOMAN’S WOOLLY’. Spare Rib, no. 114, 1982, pp. 28–29. ↩︎

- Mayne, Alison. ‘Stitchy Fingers: Making by Hand in the First Decade of “Spare Rib”’. MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture, no. 8, Dec. 2021, https://maifeminism.com/stitchy-fingers-making-by-hand-in-the-first-decade-of-spare-rib/. ↩︎

- Posener, Jill. Spray It Loud. London : Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982. ↩︎

- Brody, Jane E. ‘Homosexuality: Parents Aren’t Always to Blame’. The New York Times, 10 Feb. 1971. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/02/10/archives/homosexuality-parents-arent-always-to-blame.html. ↩︎

- Medhurst, Eleanor. ‘Lesbian Feminist Dress Codes’. Dressing Dykes, 30 July 2021, https://dressingdykes.com/2021/07/30/lesbian-feminist-dress-codes/. ↩︎

- Wilson, Elizabeth. ‘Feminism and Fashion’. Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity, University of California Press, 1987, pp. 228–47. ↩︎

- Betty Luther Hillman. ‘“The Clothes I Wear Help Me to Know My Own Power”: The Politics of Gender Presentation in the Era of Women’s Liberation’. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, 2013, pp. 155–85. ↩︎

- Steele, Valerie. ‘Anti-Fashion: The 1970s’. Fashion Theory, vol. 1, no. 3, Aug. 1997, pp. 279–95. ↩︎

- Finlayson, Iain. Denim: An American Legend. Simon & Schuster, 1990. ↩︎

ETA: Due to a cyberattack the British Library website is currently down. If you followed the first link in this post to a dead link, an archived version of the page can be found on the Internet Archive.