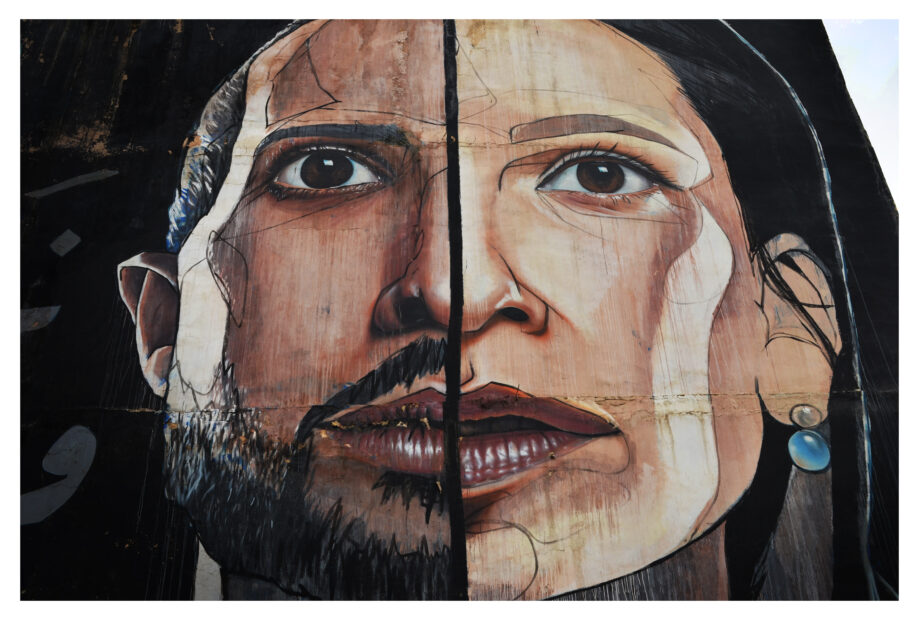

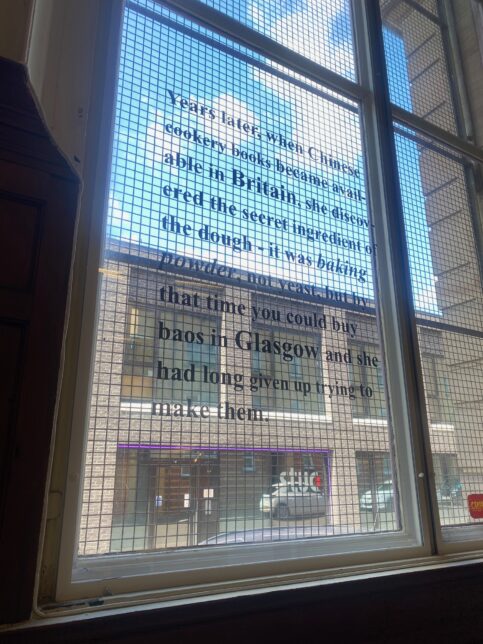

As part of our ‘GWL Origins: Pre-internet Community Building’ exhibition GWL recreated a vinyl window text site from Pam So’s ‘Mother House’ (1998) exhibited in the prior Trongate space of the Glasgow Women’s Library. Here, placement student Viki Matejova delves into the practice, works and connections the pioneering artist made while she was working with GWL.

I came across Pamela So’s work during my placement in the archives for the 30th anniversary of the Glasgow Women’s Library, and I was struck by how ahead of her time she was. Her art practice dealt with themes of Scottish Chinese and migrant identity, cultural heritage and postcolonialism. On top of this, she was active in supporting wider communities and artists. For example, in 2004 she helped to found the Ricefield Chinese Arts and Cultural Centre in Garnethill.

Remembering women artists can often be a winding road, and this was also the case here; and while I was piecing together information across sources, I couldn’t help but ask the fundamental question of why some are remembered more than others?

Her first collaboration with GWL was part of her final year project at Glasgow School of Art: it was an art installation in February 1998, and the application and response to this project is archived. The installation was named Mother House and consisted of vinyls on the windows of the Trongate premises dealing with the topic of producing art in a hostile social environment. The vinyls became part of the space, staying on until the move.

Despite what I could get from archival materials, it quickly became clear that there was a limit to what could be uncovered through records. So, myself and GWL project archivist Mae Moss sat down to talk with Adele Patrick about her memories of Pam So. They were friends as well as co-conspirators in art endeavours, So having hosted many workshops for the library while Adele was the Lifelong Learning Co-ordinator. They initially met in the mid-90s when Adele was her tutor in Glasgow School of Art.

Pam So was up against many barriers due to being a mature student, creating cutting edge work and dealing with the racism of the art world, higher education and wider society. However, she persevered: after completing her degree in 1998, she created workshops for the Women’s Library, had residencies at Syracuse University (New York) and Mount Stuart (Bute) and exhibited in Scottish galleries and art spaces. By speaking to Adele, I was able to get a glimpse into So character, “a beautiful person in every respect” and “an incredibly loyal and lovely pal” as well as a pioneering artist. The tangible records available in the archive, on the other hand, helped to bring some memories back and make her involvement with GWL concrete. I would like to expand upon three projects, which show how her work interacted with other aspects of GWL through the archival material.

Documenting 109 Trongate by Rachel Thibbotumunwe

When leaving the Trongate premises, GWL commissioned a series of photographs of women holding their favourite book in their favourite location of the library by photographer Rachel Thibbotumunwe. Pam So is pictured with Flowers by Jo Self. She is standing in front of a folder which designates the poetry shelf; it also features a red photo of her aunt, which she added to some folders as part of an art installation. Adele Patrick recalled that the aim of the photos was to make an anti-racist intervention into the collection, which simultaneously points out its gaps and includes her heritage and family in the library space.

Pam So is also featured in interview videos from the project, which have become an invaluable source of moving image from a pre-internet age: they capture the library members’ thoughts and smiles as well as the physical space of the library. These themes will be explored further in the 27th of May talk GWL Origins: Pre-internet Community Building.

Flower Power: Between the Leaves

Pam So often worked with flowers, as per her chosen book for Documenting 109. She organised a course in GWL called Between the Leaves which transformed participant’s personal collections into a memoir book. The personal collection could be anything “from chocolate ribbons to holiday beach stones”. The flyer in the archive also advertised that “she will help you create your own book using the photocopier, origami techniques and a range of unusual papers”. In 2006, she did a workshop on flowers in the library’s garden too.

She was consistently interested in flowers, and rice in her art, natural materials that had been used through generations, tracing back to her family’s migration story to Glasgow.

Ten Thousand Li

The archive houses a copy of the book Ten Thousand Li: Chinese Infusion in contemporary British Culture with a chapter on So, focusing on her 2003 exhibitions Dress Code, Chinese Chest and Role Play: “It is now easy to assume a superficial Western appearance, but Role Play invites the non-Chinese viewer to do the opposite”. Role Play was an interactive piece with postcards inviting the audience to reflect on their identity. In her own words from the book, this piece of art was a “deliberate attempt at playfulness after [her] own reckoning with the past”. Dress Code was a photographic exhibition of cross-generational Chinese women’s clothing and Chinese Chest was a moving image depiction of a grandmother handling traditional silks.

I think this set of art works shows how So worked across many mediums, from installations to videos, and how she kept interrogating the realms of the domestic, of belonging, and of normalcy. She did this through exploring her personal history as a Scottish Chinese woman, through building community and through questioning “why tradition is being put away and what it is to be replaced by”

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.