In our discourse on what it meant to be a woman during the period of industrialisation, we often find it hard to move beyond the idea of the woman in her domestic role as a wife and as a mother. Whilst this Victorian ideology of femininity undoubtedly restricted the experience of many Scottish women, it was also challenged, fought over and often contradicted by the reality of life in industrial Glasgow. 1 To understand the role that the public library would have played in these women’s lives, I think it is important to articulate the complexity and variety of Scottish women’s lives and experiences of industry. One way in which we can do this, is by examining Census data.

In the 1901 census, under the address 32 Muslin Street (which is just round the corner from the library), five young women are listed as boarding within this property. 2 These include:

- Ms. Catherine Cook, 29, a Loerge machinist

- Ms. Sarah Tomlinson, 22, a carpet weaver

- Ms. Caroline Adams, 16, a rove piercer

- Ms. Margaret E. Miller, 11, a colour weaver

- Ms. Elsie Dunlop, 17, a carpet weaver

Each of these women, regardless of their ages, are employed within local industry. These are the silent stories of the women who made Glasgow an industrial powerhouse. The lack of visibility of these women’s stories lies not in their absence from the historical record, but in our blindness to their significance. The experience for all women in Glasgow was not represented by the binary of the mother or of the daughter, engaged fully in domesticity- the reality of industrial life meant that being a woman was complex. With the emergence of the ‘New Woman’ because of increasing employment and literacy rates, how did the library serve these new and different types of women, and in which ways?

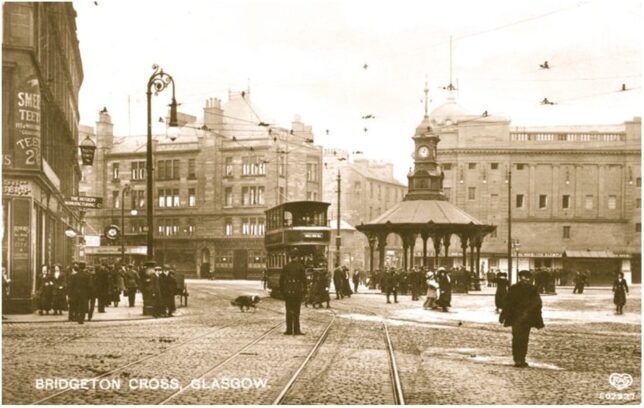

Despite the grandeur of areas such as Bridgeton Cross, for most people, life in Bridgeton at the turn of the 20th century was a fight for survival. For most, home was a one or two roomed tenement flat with a shared toilet, where there could be two, three, or even four families per landing, and up to nine to twelve families per close. 3 Growing up within these conditions, women lived with expectations of their roles both as workers and within the family- they were relied upon to care for the home and for family members, including younger siblings. 4 A continuation in the investment into the Victorian way of thinking, meant that as a girl grew, her work within the home increased. The harsh circumstances of daily life meant that many women were prematurely aged and thus relied on their children’s help- this created a cycle of dependence and entrance into domestic roles from a young age.

Whilst there was an expansion in access to education because of the 1872 Public Education (Scotland) Act, girls would often have to juggle their studies with their domestic responsibilities. In addition, many parents could not afford for girls to stay in school beyond the minimum leaving age, for need of extra hands to complete household tasks, and to contribute to the family wage slip.

A defining feature of industrialisation was the rise of factories, particularly in textiles. Bridgeton itself was a manufacturing centre for cotton-weaving and dyeing trades. Subsequently, there is a clear pattern in women’s employment, with many being employed in local factories and places of industry. Both young boys and girls in poorer families upon leaving school, had their career options limited by pressure to start earning as soon as possible. 5 This can be seen in the census data, with Ms. Margaret E. Miller, who was only 11, being listed as a colour weaver. Houses were also located near places of employment- this is known as cheek-by-jowl-living. Thus, for many during this period, their lives revolved around work and domestics.

I argue however that innovation within industrialisation at the turn of the 20th century and its impact on women’s employment freed Scottish women from the confines of Victorian femininity. Employment gave women a small measure of independence, and a taste of life outside of the home. 6 This freedom, and the increase in the amount of compulsory schooling that girls were receiving, created newly literate girls who had the desire to expand their prospects beyond marriage, motherhood and work. Innovation in the latter part of the 19th century, which led to increasing mechanisation, also freed workers from long hours within the factory and awarded them leisure time. Women now needed a way to fill this time outside of their working hour- the new ‘literate woman’ needed access to leisure opportunities out-with the public house and her home.

In his essay, ‘The Gospel of Wealth’, Carnegie states that he believed that almost 90% of donations made by philanthropists did more harm than good. 7 This is because he believed that instead of charity providing a handout, that it should provide a hand-up. I argue that the establishment of the Bridgeton Public Library did just this, by facilitating women to have a place to study and to improve their prospects, whilst meeting family obligations.

In the next blog post, we explore how the library space empowered Bridgeton’s women to negotiate popular values of femininity and temperance in the face of the emergence of the ‘New Woman’. The blog can be found here- https://womenslibrary.org.uk/2021/09/16/the-library-as-an-arena-for-self-expression/

References

1- Esther Breitenbach and Eleanor Gordon, ‘Out of Bounds: Women in Scottish Society 1800-1945’, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press (1992), https://www.worldcat.org/title/out-of-bounds-women-in-scottish-society-1800-1945/oclc/27348173, page 2.

2- Original data: Scotland. 1901 Scotland Census. Reels 1-446. General Register Office for Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland. Parish: Glasgow Bridgeton; ED: 6; Page: 25; Line: 7; Roll: CSSCT1901_263

3- W.F. Lever, ‘De-industrialisation and The Reality of the Post-Industrial City’, Urban Studies vol 6 (1991), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00420989120081161, page 13.

4- Elizabeth Carnegie and Helen Clark, ‘She was Aye Workin’: Memories of Tenement Women in Edinburgh and Glasgow’, Glasgow, White Cockade Publishing (2003), page 13.

5- W.F. Lever, ‘De-industrialisation and The Reality of the Post-Industrial City’, Urban Studies vol 6 (1991), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00420989120081161, page 23.

6- W.F. Lever, ‘De-industrialisation and The Reality of the Post-Industrial City’, Urban Studies vol 6 (1991), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00420989120081161, page 48.

7- Chris Cardiff, ‘The Paradox of Carnegie Libraries: Must Libraries be Publicly Owned?’ (2001), https://fee.org/articles/the-paradox-of-carnegie-libraries/.