‘The main consideration should be to help those who will help themselves; to provide part of the means by which those who desire to improve may do so; to give those who desire to rise the aids by which they may rise, to assist, but rarely or never do at all’. 1

Historian Michelle Garfield has argued that the public library did just this for women at the turn of the 20th century. By facilitating the exploration of new ideas and modes of learning, libraries allowed women to expand their knowledge, and empowered them to engage in new discussions and modes of self-determination. However, how was this achieved when women were not at the heart of library design?

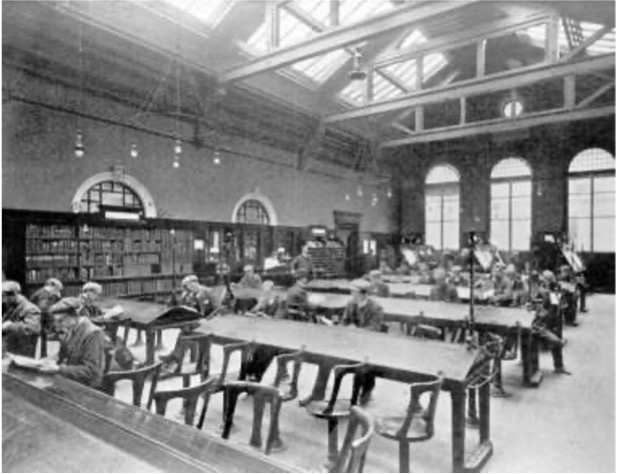

Some of the best evidence that we have for the original design of the Bridgeton Public Library is a photographic survey of the Carnegie libraries in Scotland, which was undertaken to commemorate Carnegie’s visit to Glasgow on September 17th, 1907. 2

When the Bridgeton Public Library opened in 1903, gender was spatialised, with the library designed in a way which utilised space to create a feeling of formality. Whilst the library was open to men, women and children, each group was permitted only within certain spaces. The general reading room (pictured above) was reserved for male visitors, whilst the women and children had separate reading rooms upstairs, accessed through a side entrance.

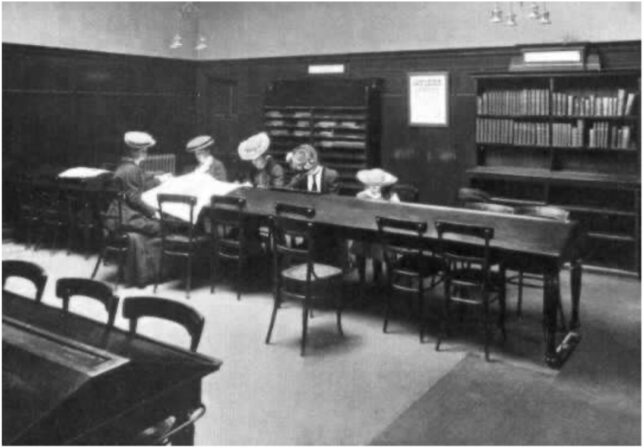

Whilst no images survive of the ladies’ reading room from the 1907 photographic study, this image from the Woodside Library in 1907, represents roughly what the Ladies’ room in the Bridgeton Public Library would have looked like. The layout and design of the library evidences the historical attitudes towards women during this period, and also allows us to analyse how the emergence of a new, literate woman was being negotiated within this space. 3

Whilst separation in this way my seem extreme to our modern sensibilities, the fact that women were even awarded their own space within the library was a massive step forward at the time. As mentioned previously, the increasing efficiency of industry in Glasgow meant that workers were now awarded leisure time out-with their working hours, which needed to be filled. Additionally, this period represented the ‘Information Revolution’, in which higher literacy rates, because of increased school leaving age, brought on the rise of a newly literate public. Thus, more people wanted access to resources within the public library not only for education, but also for enjoyment and leisure.

One of the main reasons why the middle classes backed the establishment of libraries, was to promote temperate behaviours and working-class education. These ideas were rooted in the Temperance movement, which began in the West of Scotland in the 19th century. Temperance emerged to combat the serious social problem of heavy drinking, to allow the homogenisation of working-class free time, along middle-class lines. 4 John Silk Buckingham was an important advocate for temperance, who argued that public libraries would act as counter attractions to the public house, thus lessening alcohol consumption within the working classes. 5

The Scottish Temperance Movement believed that women should lead the crusade against the masculine culture of drink, as their dominant role within the domestic and family sphere would aid in the promotion of teetotal recreation. 6 Historian Ellen Lagemann argues that Carnegie himself supported the education of women, if only because, in tune with his times, he believed that their education would promote a temperate influence, to improve the behaviour of working-class men. 7 It was believed that women held moral superiority and so, it was her place to morally uplift her family. Thus, by allowing women access to library resources, the promotion of education and temperate behaviours that this would act as catalyst to, would combat the ill-effects of urbanisation and industrialisation. 8 The working-class woman could adhere to notions of respectability by exercising her leisure time according to bourgeois feminine values.

This new influence out-with the boundaries of the home led to the emergence of the ‘New Woman’- a woman who was responsible for her own leisure, was literate and had received a more formalised education. Through access to periodicals, newspapers, and books on topics that they would not otherwise have had access to, women were offered a new perspective on life outside of the home and employment. Thus, I argue that the Public Library facilitated the creation of a new idea of what it meant to be a Scottish woman, because it awarded them with a creative, intellectual, and political space, as well as a place for assembly and association out-with the confines of work or the home. Thus, women could combat social exclusion whilst exerting their need for intellectual stimulation. 9

But, as women began to be awarded more autonomy and began to exert their own position within society, how did the library adapt to fit their needs? In the next blog post, we explore how the needs of the ‘Modern Woman’ was met, and how the women of post-industrial Glasgow utilised the library space. This can be found by following this link- https://womenslibrary.org.uk/2021/09/17/a-library-for-modern-bridgeton/

References

1- Andrew Carnegie, ‘The Gospel of Wealth’, Bedford, Applewood Books (1889), https://www.carnegie.org/about/our-history/gospelofwealth, page 2.

2- Glasgow Punter BlogSpot, ‘Glasgow Libraries, Then and Now’ (2016), http://glasgowpunter.blogspot.com/2016/03/glasgow-libraries-then-and-now.html.

3- Megan K. Smitley, ‘Woman’s Mission: The Temperance and Women’s Suffrage movements in Scotland, c. 1870-1914’, PhD Thesis, University of Glasgow (2002), http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1488/, page 110.

4- Megan K. Smitley, ‘Woman’s Mission: The Temperance and Women’s Suffrage movements in Scotland, c. 1870-1914’, PhD Thesis, University of Glasgow (2002), http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1488/, page 120.

5- David McMenemy, ‘Public Libraries in the UK- History and Values’ (2018), University of Strathclyde,https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cilip.org.uk/resource/resmgr/cilip_new_website/plss/l1_and_l2_ethics.pdf, page 5.

6- Megan K. Smitley, ‘Woman’s Mission: The Temperance and Women’s Suffrage movements in Scotland, c. 1870-1914’, PhD Thesis, University of Glasgow (2002), http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1488/, page 121.

7- Ellen Condliffe Lagemann, ‘The Politics of Knowledge: The Carnegie Corporation, Philanthropy, and Public Policy, Weslyan University Press (1989), https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article-abstract/96/3/983/55532, page 2.

8- Megan K. Smitley, ‘Woman’s Mission: The Temperance and Women’s Suffrage movements in Scotland, c. 1870-1914’, PhD Thesis, University of Glasgow (2002), http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1488/, page 122.

9- Neil MacDonald, ‘Carnegie Libraries of Scotland’, http://www.neil-macdonald.com/A2/intro.htm.

Comments are closed.