Content Warning: This blog post contains some imagery and / or written content depicting or describing experiences of gender violence and sexual assault.

When I’m not at my desk at Glasgow Women’s Library, I’m usually working away on my PhD, which I’m undertaking part-time at the University of Glasgow. It’s been a while since I posted a blog about my research, so I thought I would share some of the progress I have been making over the last year.

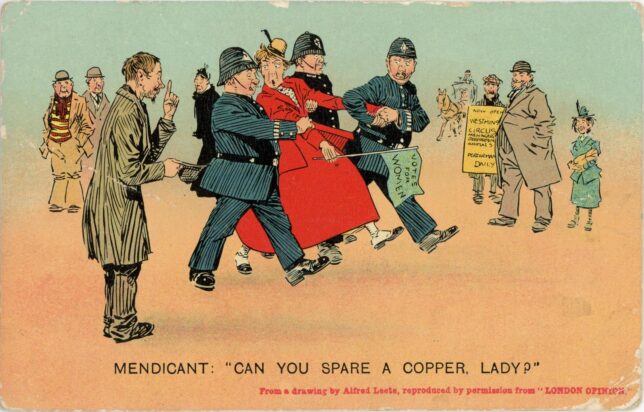

My Thesis, with a working title of Satire and Suffragettes: Women’s Rights in Everyday Material Culture in Britain 1900-1930, focuses specifically on ‘comic’ postcards produced by dozens of private companies during the suffrage era. What they have in common is the ridiculing of suffrage campaigners, and indeed women in general, in their imagery as they satirise real contemporary events. What gives an added dimension, and a fascinating insight into societal attitudes at the time, are the senders’ handwritten messages on the back of the postcards.

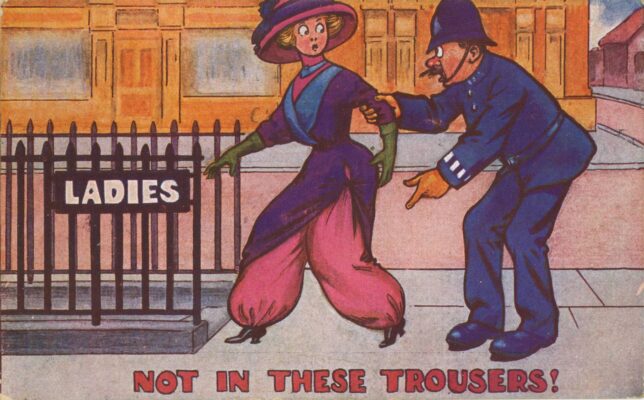

So far, I’ve written a chapter on the context for these postcards – the factors that created an appetite and demand for millions of people to buy and send them, and a chapter on the theme of dress and fashion in relation to lampooning women, especially those demanding the vote. One example of the latter is below, a satirical scene where a woman is stopped from entering the ‘Ladies’ toilet on account of her trouser-wearing (the implication is that the police officer mistakes her for a man). The phrase ‘Not in These [or sometimes Those] Trousers’ is used frequently on postcards with this theme, as I explore in detail in that chapter of my thesis.

In my latest chapter, I explore representations of gender violence as a theme for comedy and satire in the anti-suffrage postcard collection held at Glasgow Women’s Library. Within it, I dedicate a large section to looking at how postcard manufacturers (mis)represented the various forms of violence, abuse and hostility experienced by suffrage activists perpetrated at the hands of the police, in court and in prison. Alongside images of these ‘funny’ postcards I juxtapose powerful, shocking personal testimonies of the reality of the violence that suffrage campaigners endured.

From the early days of the formation of the Women’s Social and Political Union, militant suffrage campaigners consciously took actions that would provoke their arrest, a tactic to attract press and public attention. However, while suffragettes expected the law to take its course, what they unequivocally did not welcome or fully anticipate was the nature and extent of state violence and abuse they routinely endured. For nearly a decade, suffragettes and suffragists suffered intimidation, harassment, sexual and physical violence by the police, and by hostile men in crowds while the police looked on. In court and in prison they were humiliated, mistreated and violated.

There are many testimonies of police assaults against suffragettes, including on ‘Black Friday’, 18 November 1910, a date of note in suffrage history for the levels of state violence against women activists. As Parliament opened for a new session, the WSPU had organised one of their ‘Women’s Parliaments’ in Caxton Hall before processing to the Houses of Parliament in a peaceful deputation. Over 100 women were arrested, although most charges were dropped the following day. The police response was so violently extreme that a call for a Public Inquiry was made, but refused by the government. Evidence and testimonies were, however, gathered by H. N. Brailsford and Dr. Jessie Murray, which told of multiple physical and sexual attacks by the Police on women. Victims and witnesses,

‘… testified to deliberate acts of cruelty, such a twisting and wrenching of arms, wrists and thumbs; gripping the throat and forcing back the head; pinching the arms; striking the face with fists, sticks, helmets; throwing women down and kicking them; rubbing a woman’s face against the railings, pinching the breasts; squeezing the ribs.’ 1

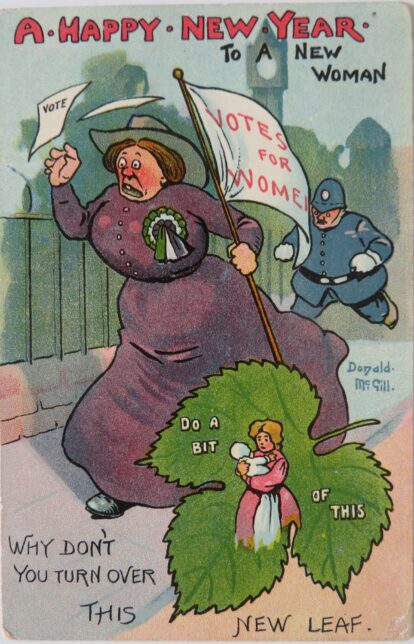

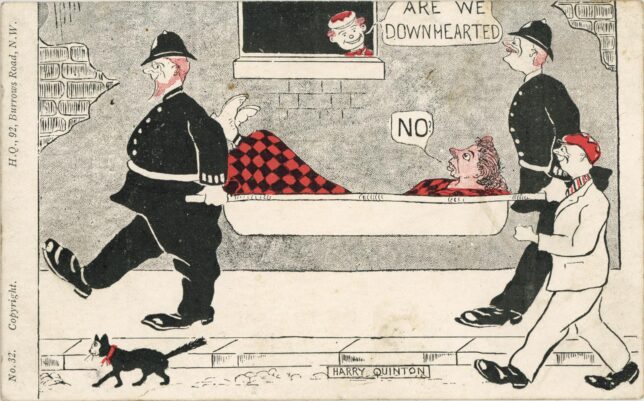

Against this backdrop, anti-suffrage postcards became part of a propaganda war, with their representations minimising such violence and ridiculing women. Postcard manufacturers frequently depicted suffragettes being arrested as conventionally unattractive caricatured older women, and police officers as benign and jovial.

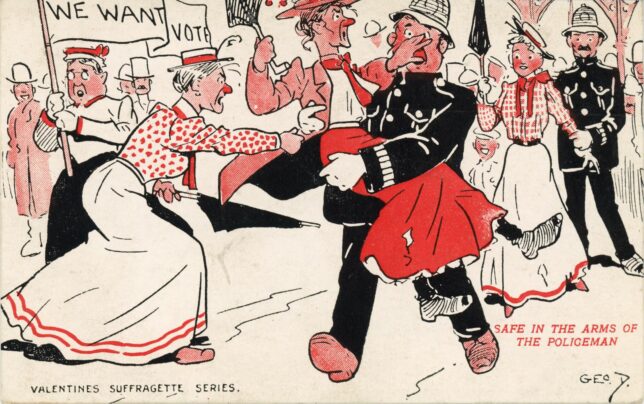

They also produced sardonic representations of women militants as the instigators of violence, ‘fighting back’ against the state, typically against police officers during arrest.

There are some elements within the images of suffragettes ‘fighting back’ that do have a factual basis. Extreme violence towards suffragettes by the police, and by men in gathering crowds, started early in the militants’ campaign. Sylvia Pankhurst recalls a public meeting in Parliament Square held on 30 June 1908, with 5,000 foot police and 50 mounted present, and the sight witnessed by Lloyd George, Winston Churchill and Herbert Gladstone. She recounts the women speakers being,

‘…torn by the harrying constables from their foothold and flung into the masses of people … Then roughs appeared, organized gangs, who treated the women with every type of indignity… The roughs were constantly attempting to drag women down side streets away from the main body of the crowd’ 2

In this context, women built in strategies for their self-defence. Some were simple and practical: Leonora Cohen describes inserting corrugated cardboard into their sleeves to stop people pinching their arms.3 Other approaches carried more intent – hatpins and umbrellas employed as defence weapons, as represented in some of these postcards, while other items, such a stones and hammers, were carried to use for damage to property. On 5th December 1908, suffragette Helen Ogston’s self-defence weapon of choice was a dog whip, which she used against stewards trying to remove suffragettes from an event where Lloyd George was addressing the Women’s Liberal Federation. Helen Ogston told Pankhurst, that she had used the whip as,

‘A man put the lighted end of his cigar on my wrist; another struck me in the chest. The stewards rushed in to the box and knocked me down. I said I would walk out quietly, but I would not submit to their handling. They all struck at me. I could not endure it, I do not think we should submit to such violence. It is not a question of being thrown out; we are set upon and beaten.’ 4

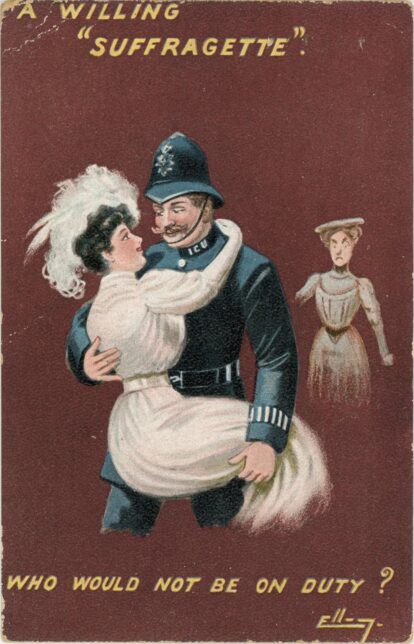

Some postcards show suffragettes not just literally, but ‘willingly’, in the arms of policemen. Below, an older women looks scornfully upon a young, more conventionally beautiful feminine suffragette being romantically carried away by an obliging police officer. The look of the younger woman is a look of love, in contrast to the older woman’s disapproval.

Posted on 14th May 1909 the sender, a policeman himself, writes,

‘Manchester is a strong hold of suffragettes. It’s allright being a Bobby. Rem me to Willie. Hope all are well. Lovely weather here’

The postcard image, and the sender’s message, are suggestive in a number of ways: that there exists a mutual attraction, an agreeable and beneficial arrangement between the men of the police force and the women of the suffrage movement; that the policemen are gentle and romantic figures; the potential for finding romance in the course of militancy is not just possible, but perhaps the very reason that young women engage in that activism; that attractive suffragettes are easy to pick up if you are a policeman – they are there for the taking; and that older women hold contempt for younger women, that some are sour, jealous, ugly spinsters.

Sylvia Pankhurst suggests that there was an active policy of stoicism in the militant suffragette movement about their treatment, while Leonora Cohen, herself a victim of violence and imprisonment, sums up the pragmatism of the movement,

‘I’d gone out knowing that it was breaking the law and we’d done it for a purpose, and the object of course was for publicity’5

The representations in these postcard images disguise the realities of militant life and the normality of experiencing violence for the cause of women’s suffrage. There are, of course, parallels with today – police brutality against women, and abuse in the criminal justice system have sadly not been consigned to history.

Publisher Unknown, No. 2142. From the collection of Glasgow Women’s Library

If you are interested in my research topic, hold any collections of suffrage memorabilia, or have any comments, please email me at sue.john@womenslibrary.org.uk or contact me on Twitter @Sue_John_

Footnotes

- Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffrage Movement: An Intimate Account of Persons and Ideals (London: Virago, 1977), 343. ↩︎

- Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffrage Movement: An Intimate Account of Persons and Ideals (London: Virago, 1977), 285-7. Pankhurst adds, ‘So enraged were Mary Leigh and Edith New that they went to Downing Street and flung stones through the Prime Ministers window – the first act of damage ever committed by suffragettes’. ↩︎

- Leonora Cohen, discussing her memories of being imprisoned for her suffrage activism. Interview 18b), 00:26 minutes in. The Women’s Library, The London School of Economics, “The Suffrage Interviews”. The London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.lse.ac.uk/library/collection-highlights/the-suffrage-interviews. ↩︎

- Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffrage Movement: An Intimate Account of Persons and Ideals (London: Virago, 1977), 297. ↩︎

- Leonora Cohen, discussing her suffrage activism. Interview 18b), 03:09 minutes in. The Women’s Library, The London School of Economics, “The Suffrage Interviews”. The London School of Economics and Political Science. ↩︎