Please note: this post refers indirectly to police brutality and institutional racism & classism.

Over the last eighteen months, many of us have gotten involved with community organising – some for the first time – to ensure that our friends and neighbours have access to food, healthcare, money, and other essential resources during a pandemic that has upended our lives. These efforts to care for each other have usually taken the form of mutual aid groups; organised via social media, local initiatives have popped up everywhere. Elsewhere, chaotic institutional handling of the pandemic – which has seen university students locked into their accommodation and private renters losing their income – has sparked global rent strikes and calls to freeze or abolish rent. Although grassroots organising and mutual aid have risen to the fore since March 2020, they didn’t arrive from nowhere: in Black communities and working-class neighbourhoods, they’ve long been cornerstones of larger struggles for basic rights and freedoms. In this final post in a blog series examining feminist housing activism in the 1970s and ’80s, we’ll explore some of the collectives who have led the fight for a place to call home.

Black women and mutual aid

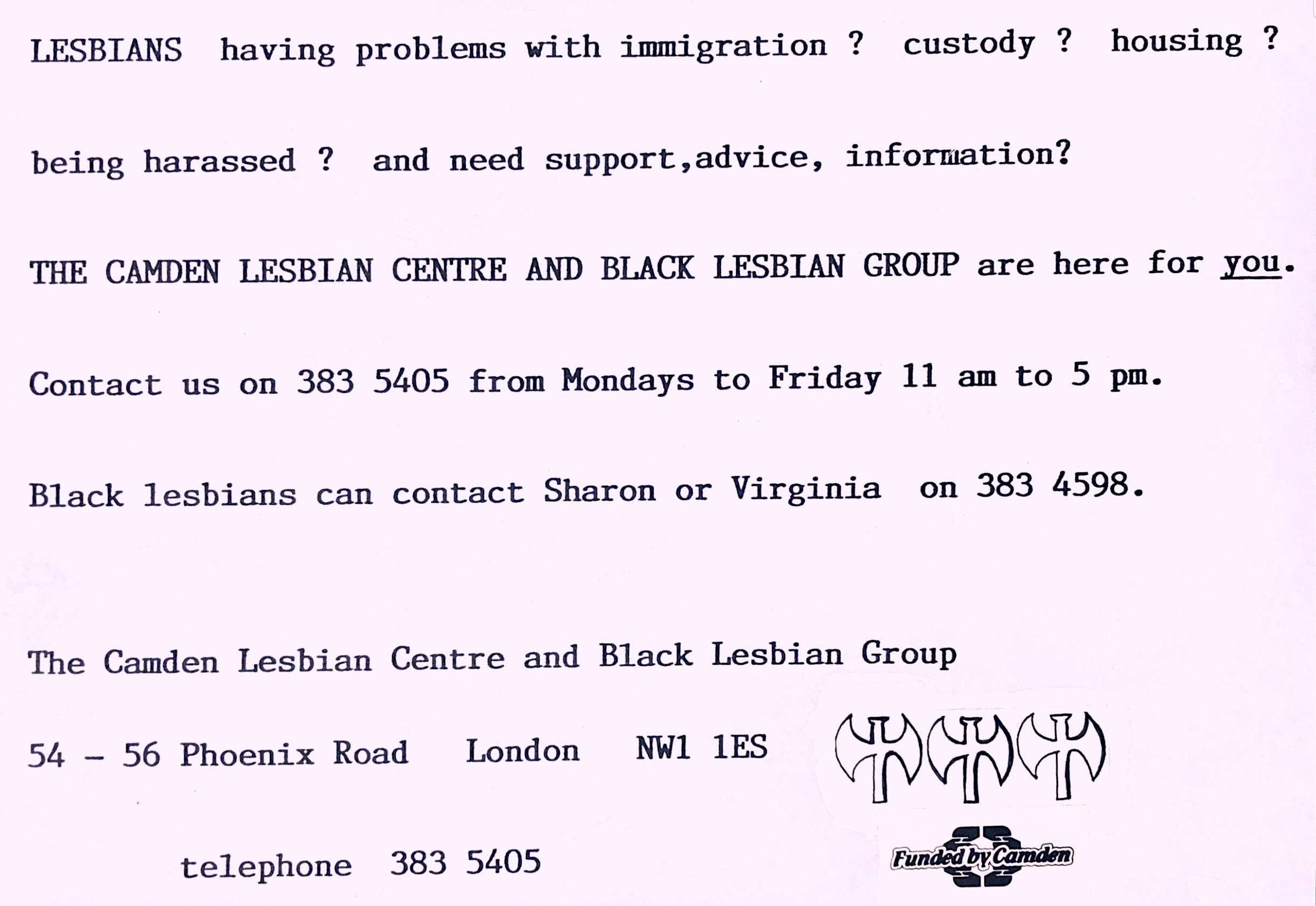

During the first UK lockdown, mutual aid groups popped up all over the place. But such initiatives have long existed in Black communities – as activist and community organiser Eshe Kiama Zuri explains:

Black and working-class communities [have] built mutual support and shared knowledge into their activism and ethos. They didn’t always use the buzzword “mutual aid” to name it, but with their centring of family and their inclusive diaspora community focus, they put forms of decolonial mutual aid into practice.

Zuri traces the roots of community aid back to groups engaged in antiracist work and Black liberation struggles, like the Black Panther Party and the Organisation for Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD), a UK-wide coalition of women of colour from different backgrounds and political perspectives. There’s another important distinction to make here – just as Zuri points out that Black and working-class communities haven’t always named their work as “mutual aid”, women-led organisations like OWAAD didn’t necessarily position themselves as feminist groups. In the 1970s, mainstream feminism was still overwhelmingly white and middle-class – in The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain, one community organiser articulates the key difference between white feminism and the priorities of many Black and brown women:

[Abortion access and wages for housework] were hardly burning issues for us – in fact they seemed like middle-class preoccupations. To begin with, abortion wasn’t something we had any problems getting as Black women – it was the very reverse for us! And as for wages for housework, we were more interested in getting properly paid for the work we were doing outside the home as nightcleaners and in campaigning for more childcare facilities for Black women workers.

One group that led efforts to organise Black communities against structural racism was the United Black Women’s Action Group. When founding member Martha Osamor came to the UK from Nigeria in 1963, she moved to a housing estate in Hornsey, North London, where conditions for Black residents were overcrowded and poorly maintained by the housing association. In the summer of 1977 Martha and other Black tenants called a mass meeting to discuss the living situation, after which they began to meet regularly at a local domino club; the women quickly found that their concerns were not listened to or taken seriously by many men amongst them, who used the club as a social space to relieve the stresses of working life. Unhappy with this, the women mobilised to form the UBWAG – a member recalls how they developed:

At our meetings, we started by trying to educate ourselves, by looking first at our Rights: rights on arrest, housing rights, women’s rights and our children’s education, particularly school suspension.

Knowing one’s rights was (and is) essential for those brutalised and discriminated against by the state. By exploiting a clause in the 1824 Vagrancy Act, police officers were able to stop, search and arrest anyone on the grounds of a suspicion; this was known as the sus law, and the police used it to disproportionately target Black and brown communities (boys and young men in particular). The UBWAG trailblazed the Scrap Sus campaign, a series of coordinated actions and public meetings to stop the police’s racist harassment and to protect Black residents in their own neighbourhoods. This activism unfolded in the face of open hostility and attacks on Black and brown communities from all sides – not least by the police, who defended white supremacist rallies whilst confronting antifascist and antiracist counter-demonstrators. Although the sus law was repealed, police stop and search powers continue to harm Black, working-class, and communities of colour today.

Scrap Sus broadened the Group’s horizons as they met with Black women from across London facing the same issues with no legal protections or recourse to justice. To extend their reach and mobilise more Black women, the BWAG became a subgroup of OWAAD in the early 1980s. These groups, along with a host of other female-led Black community organisations, would play a pivotal part in keeping minoritised people safe and sustaining one another through initiatives such as the Black Supplementary School Movement.

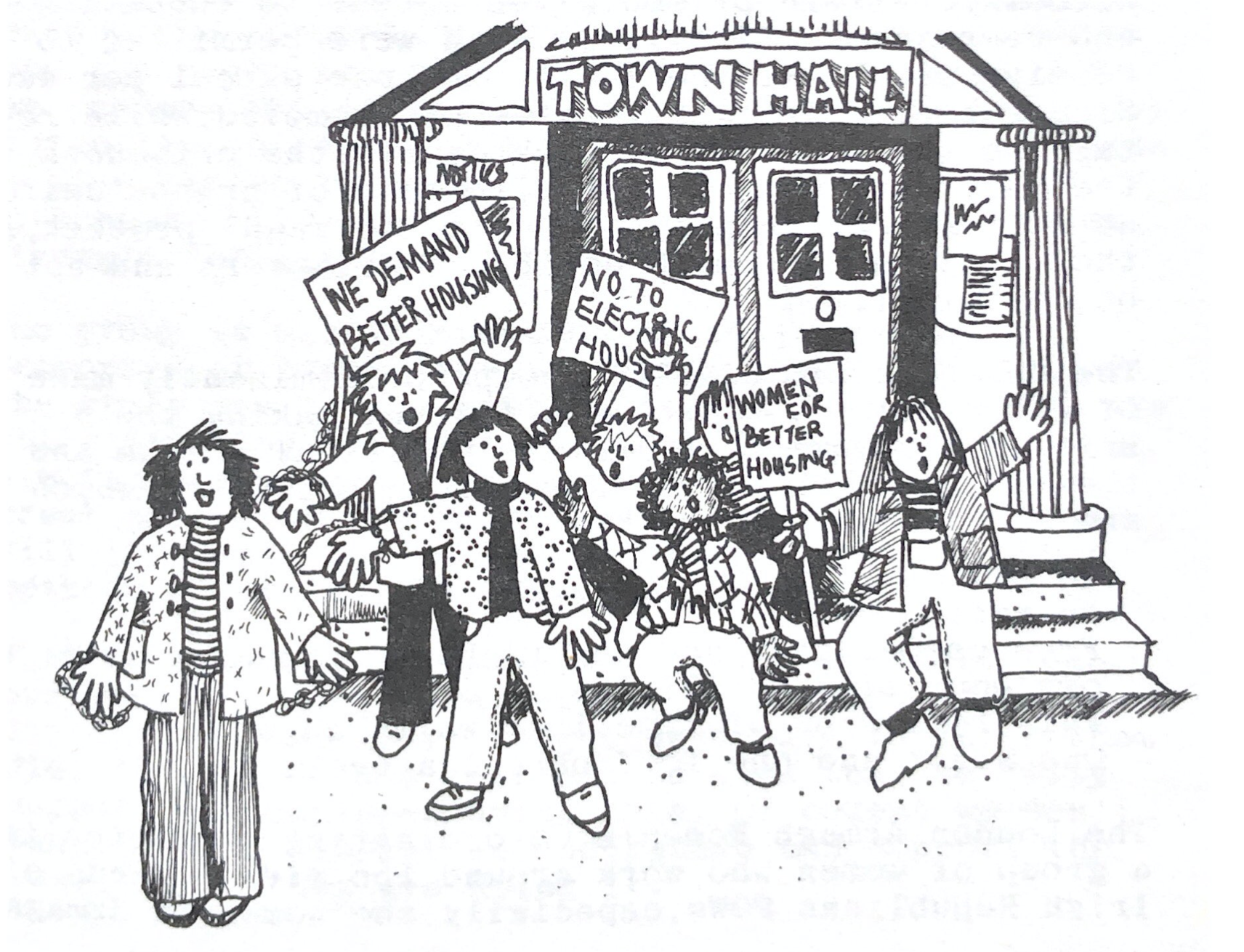

‘Coming alive hurts!’: Mobilising working-class women in South Wales

In May 1978, five women in the coal-mining town of Pontypridd, South Wales, chained themselves to a fence to protest the damp conditions and inadequate heating provision in their council houses on the Glantaff Farm Estate. These women had never been involved in political activism before – they didn’t think of themselves as political up until this point – but the attention of the local media brought considerable political pressure with it, and from this spontaneous act of civil disobedience came many, many more. After two long years of petitioning, meeting with local officials, and public demonstrations, the Glantaff women won their campaign for the installation of gas heating; rather than sitting on their laurels, they then they helped another group of women in Penarth, near Swansea, to organise for better conditions in their council houses. When they won that campaign, the extended group formed the South Wales Association of Tenants (SWAT) and took their energy, resources and skills to other council tenants who needed their help.

Up until then, most of the women involved had lived rigidly traditional lives, subservient to their husbands and always organising around domestic chores – one woman remembers attending a demo at the House of Lords in her slippers after sneaking out so her husband wouldn’t stop her. SWAT brought radical new ideas and experiences to the centre for these women, and it taught them how to work together to create better lives for themselves. In the Women in Collective Action anthology (1982), one member reflects:

If [politicians and academics] would show us how to improve our standard of living instead of just reading books and talking, we might get somewhere. I know now that it’s no use asking for help from political parties and trade unions. We have to help ourselves and we can do it by working together and helping each other.

Many SWAT members channelled their passion for political organising into coordinating rent strikes and helping other council tenants to force their housing authority to undertake repairs. For all of the women involved, their perceptions and expectations of themselves were irrevocably altered – in the words of one SWAT organiser, ‘I would say we’ve had our eyes and minds opened, but I’ve learnt to say that we had our consciousness raised.’

Picturing community activism

Franki Raffles (1955-1994) was a social feminist documentary photographer based in Edinburgh. Raffles travelled extensively, photographing women in China, Tibet, the USSR, Israel, Mexico, and closer to home, on the Isle of Lewis, where she renovated a farmhouse and built herself a darkroom. Amongst this rich visual history of ordinary women’s lives are photographs of women living and working across Scotland, captured as part of various freelance projects and commissions Raffles undertook for community groups, trade unions, local authorities, and the NHS. If you head up to the first floor gallery space at GWL, you’ll find a selection of these photographs on display as part of our current exhibition, Life Support: Forms of Care in Art and Activism. Many of these images are intimate depictions of women in their homes, with friends and dependents, or fighting for their community spaces.

Muirhouse Community Playground Action Group, Edinburgh (c.1980s). © Franki Raffles Estate, all rights reserved. Image courtesy of University of St Andrews Library and Edinburgh Napier University.

What’s striking about Raffles’s images of these women is her empathy and presence in the scenes she captures. Her subjects aren’t posed or distant; they’re dynamic, busy working in the home or the streets. There’s little distance between the photographer and the people being photographed, likely because Raffles developed close relationships and actively collaborated with the women she pictured. Community action groups like the one pictured above, taken on the Muirhouse Estate in north Edinburgh, were spearheaded by women, as were campaigns for the survival of women’s centres – vital support systems for women on the estates – like Bathgate Women’s Aid (below). Franki Raffles’s images offer an important visual record of women’s care and activism where other archives don’t or can’t do so; these photos are radical in their tenderness, their refusal of stereotypes of working-class women’s lives.

Save Bathgate Women’s Aid demo, Edinburgh (c.1980s). © Franki Raffles Estate, all rights reserved. Image courtesy of University of St Andrews Library and Edinburgh Napier University.

Rachel Boyd and Weitian Liu have curated a selection of images from the Franki Raffles Archive as part of Life Support, on display until 16 October. Women in Collective Action also features in the exhibition, on display in the foyer welcome wall at GWL.

About the author: Lucy Brownson (she/her) is an archivist and PhD candidate at the University of Sheffield. In her doctoral research, Lucy explores the history of archival practices at Chatsworth House through a feminist lens. She’s also an organiser of Sheffield Feminist Archive, a community archive documenting grassroots feminism in the Steel City. Lucy is undertaking a placement in the GWL archives from July-October 2021; you can keep up to date with her work on Twitter.

References

Harmit Athwal & Jenny Bourne, ‘Martha Osamor: unsung hero of Britain’s black struggle’, Institute of Race Relations (IRR) blog (17 Nov 2015)

Jenny Bourne, ‘Lewisham ’77: success or failure?’, IRR blog (19 Sept 2007)

BBC News, ‘Coronavirus: Students ‘scared and confused’ as halls lock down’ (26 Sept 2020)

Brixton Black Women’s Group, ‘Black Women Organizing’, Feminist Review (1984)

Beverley Bryan, Stella Dadzie & Susan Scafe, The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain (1985)

Ann Curno & Association of Community Workers, Women in Collective Action (1982)

Ryan Erfani-Ghettani, ‘Black history and black struggle: the past in the present’, IRR blog (23 Mar 2016)

Franki Raffles Archive images via Edinburgh Napier University & University of St Andrews

George Padmore Institute, ‘Black Education Movement’

Joseph Maggs, ‘Fighting Sus! then and now’, IRR blog (4 Apr 2019)

Richard Partington, ‘Call to freeze all UK private rents to help 1m workers at risk of losing jobs’, Guardian (4 May 2020)

Diane Pien, ‘Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program (1969-1980)’, Black Past blog (11 Feb 2020)

United Black Women’s Action Group memo (1978), via Black Cultural Archives

Eshe Kiama Zuri, ‘‘We’ve been organising like this since day’ – why we must remember the Black roots of mutual aid groups’, gal–dem (5 Jun 2020)