Where are you reading this blog? Are you on the move, commuting to work or school? Perhaps you’re in a public space like a park or a café. Me, I’m writing this from the rickety kitchen table of my rented tenement flat in Glasgow. I’m only here for three months, so there isn’t much point in trying to shape the space around me, but I’ve picked up a few bits and pieces for my room – a £1 clock from a charity shop, a GWL postcard, the occasional bunch of flowers – to make it feel more mine, you know? My legs are bruised from scrapping with my bike each day as I lug it up and down the three flights of stairs between my front door and the street below. This isn’t my space, so things aren’t exactly as I’d want them to be; there are flaws and bumps (literally, as a pedal hits my shin).

Now consider your own surroundings – do they work for you? If not, why not? If you could build this space yourself, what would you do differently? These questions have been at the heart of feminist efforts to create functional, accessible homes and social spaces for decades. In this three-part blog, we’ll explore how feminist housing activists have taken matters into their own hands where the state has failed to provide for them them, from squatting houses to taking to the streets.

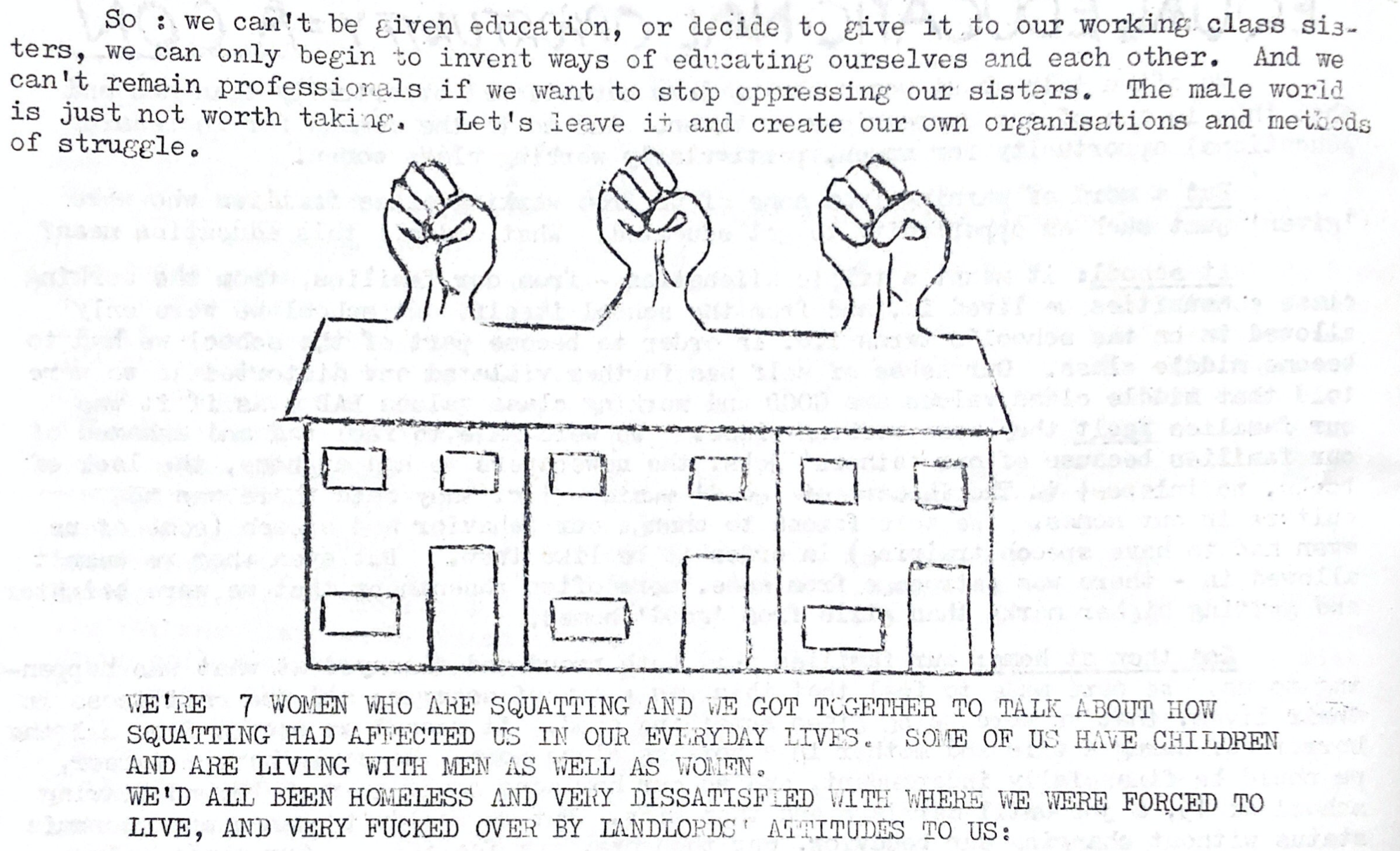

Women-only squats

The UK’s feminist squatting movement came into its own in the early 1970s. Amidst a housing crisis and soaring youth unemployment rates, many of the urban neighbourhoods surrounding major cities like London, Glasgow and Manchester became thriving pockets of counterculture as communities of squatters moved into stretches of derelict Victorian housing scheduled for demolition. The family squatting movement of the late ’60s saw coordinated campaigns like the London Families Squatting Association, which began occupying and restoring vacant council-owned buildings for families awaiting council housing; many families had been on waiting lists for literally years, and the only alternative to squatting was constant displacement from hostel to bedsit to refuge. From this point onward squatting began to take root as an alternative and highly collectivised mode of living that directly challenged private property ownership and landlordism – a necessity for some, a political choice for others, and a combination of these two factors for many.

Women-only squats proliferated across Islington, Camden, Southwark, Westminster and Kensington in the mid-1970s, many of which were formed as a community response to the lack of state provision for women’s centres and refuges for women and children escaping domestic violence. Near to Kings Cross station, just around the corner from what would later become the UK’s only dedicated lesbian centre, a cluster of around six women-only squats became an informal women’s centre by virtue of a hand-painted sign and its residents supplying free pregnancy tests – one of countless examples of women caring for each other in the absence of any institutional support. In place of the street food vendors and sourdough bakeries that now line Hackney’s Broadway Market, rows of lesbian communes made this street a metropolis of lesbian feminist activism. Given that lesbians were marginalised within the Women’s Liberation Movement and the Gay Liberation Front, both of which typically overlooked their specific needs and experiences, these communes – and the circuit of pubs, cafés and social spaces that quickly sprang up around them – became a much-needed space to build their own community. Because the women who moved into these otherwise derelict houses would often repair them and keep pest infestations at bay, local residents would alert them to vacant properties in their areas before local authorities vandalised and then demolished them; by the late 1970s, there were reportedly more than fifty women-only squats in London Fields.

Squats functioned as places for women to live and care for each other first and foremost, but they became much more than that – in the words of Prof Christine Wall:

Squatting provided the physical and spatial infrastructure for the feminist activism in 1970s London seen in women’s centres, refuges, nurseries, bookshops, art-centres and workshops.

In feminist squatting, we can trace the root of many strands of women’s political and civic lives that would gain traction and burst into the mainstream in the 1980s. Communal living also meant communal parenting arrangements for women with children – one woman living in a women’s squat in Oxford, writing in the Libertarian Women’s Network Newssheet c.1972, explains:

When I wasn’t squatting I was stuck in all the time because I couldn’t find anyone to look after the kids, but now I can ask someone and if they can’t help, they usually know someone who can. Squatting forms a network you can go to.

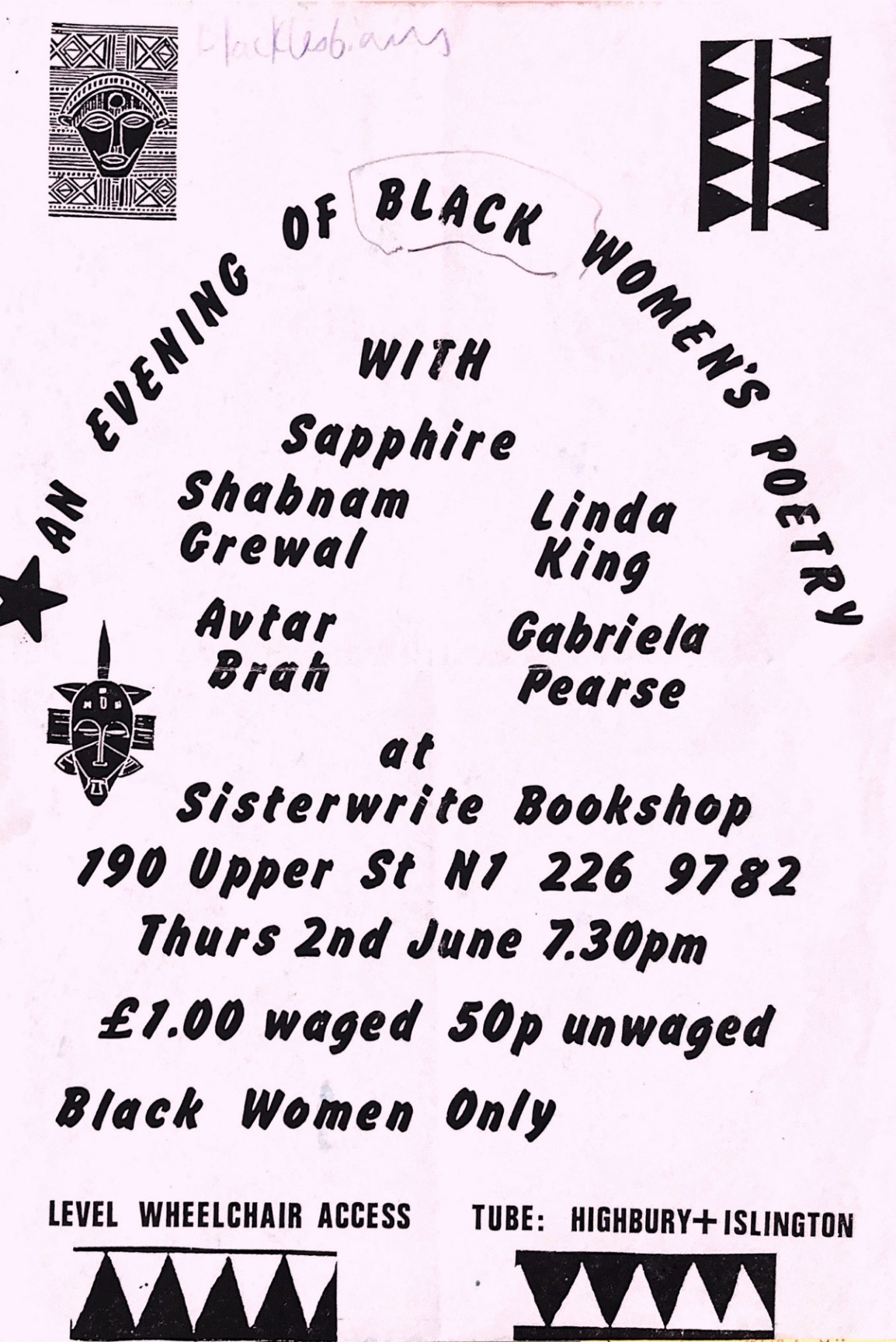

For those in the squatting movement, the provision of crèches and childcare at women’s centres and events was a foundational element rather than a hard-won privilege. Relatedly, the co-operative working structures at countless feminist businesses established in the 1980s – including Islington’s Sisterwrite and Edinburgh’s Womanzone bookshops – took what women had learned from living communally, sharing resources and distributing work evenly, and built it into a business model. Bookshops in particular played a key role in bringing feminism out of close-knit countercultural circles, making it accessible to any woman and offering a kind of affirmation through information for those coming to terms with their feminism and/or their queerness.

As councils began to license and regulate squatting in the 1980s, many squats turned into short-life housing co-operatives. Some squatters were granted permission to remain in derelict properties for the years before redevelopment started, on the condition that they repair and clean up the property. Many women took courses to learn how to wire, plumb and plaster their houses – others, meanwhile, took things a step further and began learning how to rebuild their houses or build entirely new ones in vacant lots. In the next post in this series, we’ll explore feminist efforts to build homes and spaces themselves, together, from the ground up.

About the author: Lucy Brownson (she/her) is an archivist and PhD candidate at the University of Sheffield. In her doctoral research, Lucy explores the history of archival practices at Chatsworth House through a feminist lens. She’s also an organiser of Sheffield Feminist Archive, a community archive documenting grassroots feminism in the Steel City. Lucy is undertaking a placement in the GWL archives from July-October 2021; you can keep up to date with her work on Twitter.

References:

Lucy Delap, ‘Bookselling and the feminist past’, OUPblog (2 May 2016)

Feminist Library blog, ‘In conversation with members of Sisterwrite Collective’ (3 July 2020)

Layers of London, ‘Sisterwrite Bookshop’ (2020)

Squatting London blog, ‘Family Squatting Campaign, 1968’ (8 Jan 2018)

Sarah Taylor, ‘Queer Neighbourhoods: Lesbian Squats in London Fields’, East End Women’s Museum blog (22 Feb 2021)

Lucy Uprichard, ‘How Feminist Bookstores Changed History’, Vice (25 Sept 2018)

Christine Wall, ‘Sisterhood and Squatting in the 1970s: Feminism, Housing and Urban Change in Hackney’, History Workshop Journal 83.1 (2017)

Waltham Forest Echo, ‘The East End women who fought for gay rights’ (15 Mar 2020)