Hello! My name is Myriam, and I am doing a summer student placement at Glasgow Women’s Library. I am currently attending Lyon’s Institute of Political Studies and in September I will start a master programme in Korean Studies. I am excited to be part of GWL and learn more in my time here!

If you have been to the library recently you may have noticed the banner next to Front of House on which is written “Safeguarding the history of your grandmothers, Hearing the memories of your mothers, Providing inspiration for your daughters”. It is in the spirit of this trans-generational effort to uplift and support women, past and present, that I decided to write this article on great Korean women in history.

I have been interested by Korean society and history for many years now. I speak Korean and have visited South Korea before. The more I learnt the more I realised how shallow our understanding of Korea is in Europe. Often, all we know is that Korea was separated in two after the Korean War [1950-1953] and that the North has a communist regime. However, Korean history is much older and much more complex than that, and it has a lot to offer to anyone willing to learn.

I am not here however to give you a summary of Korean history, it would be reductive and simplifying. Instead, I would like to mention some of the remarkable women who have made history. First, I would like to preface by highlighting the fact that Korean history has suffered the same fate as European history, where women and their contributions have been ignored, suppressed, or forgotten and the women represented in this article are some of many more brilliant Korean women.

For some spatial perspective, here is a map showing all the birthplaces of the women featured in this article. A great way to discover Korean geography from a new angle!

Korean Women in Pre-modern History

Queen Seondeok of Silla [선덕여왕] (595~610-647), first reigning queen of Silla

Before what we know as Korean territory was united, there was an era called “The Three Kingdoms”. One of them was Silla, situated on the East coast of what is now South Korea. The legend says that after hearing that her father -the king- was thinking of passing down the throne to his son-in-law, future queen Seondeok asked her father for a chance to prove herself worthy of reigning. In 632, she officially became Queen Seondeok of Silla, becoming the first known reigning queen in Korean history. Though some men disagreed with the idea of a woman inheriting the throne and organised a coup, Queen Seondeok stayed in power until her death in 647, after which the throne was given to a female cousin. Her legacy is one of a caring and kind leader to her people who promoted the spread of Buddhism in Silla.

Shin Saimdang [신 사임당] (1504-1551), painter

During Joseon dynasty [1392-1919] Shin Saimdang was mainly remembered as the ideal Confucian mother, having raised the Confucian scholar Yi I (이이). However, her talent as a painter is undeniable and she is one of the famous famous female painter in Korea. Her most popular paintings are ones of flowers and nature, with delicate and precise brush strokes and bright colours. She also was a calligrapher and writer. Shin Saimdang is the only woman to appear on Korean money as her face is on the 50 000 won bill. However, portraits of women were rare during the Joseon dynasty and therefore the face shown on the bill is only a guess at what she would have looked like.

Hwang Jini [황진이] (1506-1560), gisaeng (artist and entertainer)

Hwang Jini, nicknamed Myeongwol [명월] or Bright Moon, is probably the most famous gisaeng in Korean history. A gisaeng is a female entertainer trained in dancing, singing, playing instruments as well as literature and the art of conversation and hosting. It existed different categories of gisaeng depending on one’s skills, reputation, and clients. Hwan Jini was known for her extreme beauty and wit. She famously created a riddle and whoever could solve it would be allowed to spend the night with her as she wanted someone whose wit was equal to hers. Only one man succeeded. Though her beauty has made history, her face is unknown to us as no official painting of her has ever been discovered. Her talent has also only been partially transmitted as many of her poems were not recorded.

Lady Hyegyeong [혜경궁 홍씨] (1735-1816), Korean crown princess and author

Lady Hyegyeong was born outside of the palace from a scholarly family. At 9 years old she was selected to be married to prince Sado [사도세자], heir of the throne, and became a crown princess. She did not, however, ever become a queen as her husband was killed at 25 by his own father, the king Younjo, after years of violent and disturbing behaviour. Lady Hyegyeong had a long and difficult life of which we know the details of only because she chose to put it in writing. Her memoirs, titled “Records written in silence” in Korean [한중록] detail her life from childhood to old age with the tragic fate of her family, from the death sentence of her uncle and brother to the suffering cause by her husband. Lady Hyegyeong, due to her position as a women in the royal family, allows us into the intimacy of Korean noble women in a time where even their first names were not recorded (including Lady Hyegyeong’s).

Modern and Postmodern History

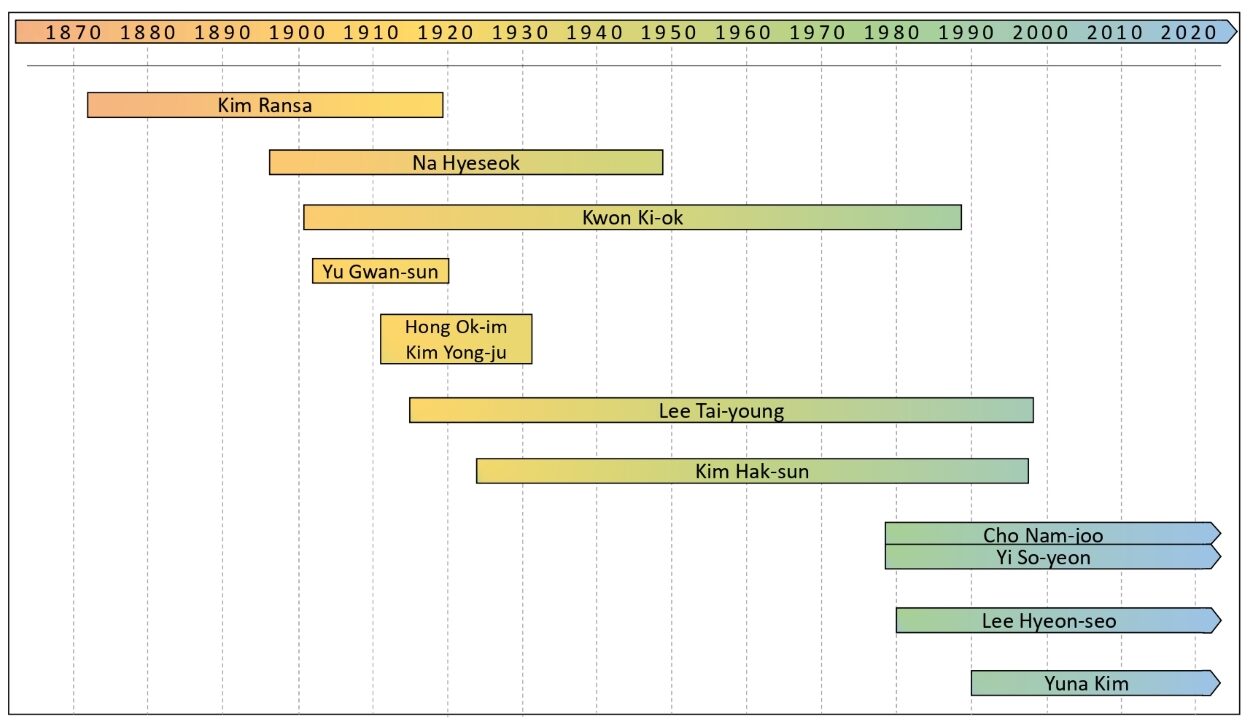

The women discussed in this part are much closer historically to each other and, for some, their lives even intertwined. Here is a timeline superimposing the lives of all these brilliant women.

Kim Ransa [김란사] (1872-1919), Korean independence activist

Kim Ransa is a well-known Korean teacher and activist. Though schools did not accept married women, she convinced Ehwa Hakdang to accept her in 1896 and then went on to study in Ohio Wesleyan University to earn a bachelor’s degree. After Japanese colonial annexation of Korea in 1910, Kim Ransa fought for her country’s independence, to the point of helping to organise a secret Korean delegation to send to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Sadly, while on her way to Paris, Kim Ransa passed away due to unknown causes, though some believe she was poisoned.

Na Hyeseok [나혜석] (1896-1948), painter, writer and activist for women’s rights

Na Hyeseok was part of the first generation of Korean women to go to university, creating a socio-political movement called “New Women”. Renown painter, she had achieved much success both in Japan and Korea. She was also a radical feminist writer, always fighting for women’s rights in Korea. She was especially opposed to the societal requirement of chastity for women. In 1935 she wrote in an article “Chastity involves neither morals nor laws. It’s merely taste.” Sadly, she died alone and poor, abandoned by her family and friends after a divorce, and was subsequently used as a cautionary tale against promiscuity and rebellion. However she is now a symbol of courage for feminists around the world.

Kwon Ki-ok [권기옥] (1901-1988), first Korean female aviator

Kwon Ki-ok is the first Korean female aviator, and one of the first female pilots in China. After her involvement in the Korean independence movement, Known Ki-ok went into exile in China. As a teenage girl she dreamed of flying and once in China, though she had to learn a new language and was going against all gender conventions, she managed to enter of the Republic of China Air Force. After Korea was liberated in 1945, Kwon Ki-ok went back to her country and helped the creation of the Republic of Korea Air Force.

Yu Gwan-sun [유관순] (1902-1920), Korean independence activist

Yu Gwan-sun was a Korean independence activist. Taught by Kim Ransa and coming from a family themselves fighting for Korean independence, Yu Gwan-sun showed an infallible faith in her country’s future liberation. At only seventeen-year-old, Yu Gwan-sun was arrested at a pro-Korean independence protest at which her two parents were killed. Though tortured by policemen, Yu Gwan-sun stayed true to her ideals and showed true bravery until her premature death at their hands.

Kim Yong-ju [김용주] (1910s-1931) and Hong Ok-im [홍옥임] (1910s-1931)

Kim Yong-ju and Hong Ok-im met in high school and fell in love with each other. Kim Yong-ju was said to be well educated and gentle. Hong Ok-im had a tumultuous personality and did not do well in school. Going against all societal expectations, the two lovers continued their relationship even as Kim Yong-ju entered a marriage arranged by her family. In April 1931, Kim Yong-ju and Hong O-gim, seeing no future for themselves, chose to jump in front of a train together. While this is a tragic story, Kim Yong-ju and Hong Ok-im’s love stays in history as a reminder that queer Korean women have always existed in society.

If you are interested by the life experience of Korean women under Japanese colonial and queerness in East Asia, the novel “Pachinko” by Min Jin Lee is available at GWL.

Lee Tai-young [이태영] (1914-1998), first Korean female lawyer

Lee Tai-young studied in the hope of one day becoming a lawyer but her dreams were initially put to a stop after her husband was arrested for “anti-Japanese activities” during the colonial era. However, she later became the first woman to join Seoul National University in 1946, and she earned her law degree there. Even under the dictatorship of Park Chung Lee, Lee Tai-young did not stay quiet on the issue of civil liberties and consequently was disbarred. However, it did not stop her as she transformed her cabinet into a legal aid center. She later became one of the first female judges in South Korea. Women issues were at the centre of her career and she published many books about, and for, women.

Kim Hak-sun [김학순] (1924-1997), first victim of sexual slavery under the Japanese Empire to publicly speak up about her experience

Kim Hak-sun was part of the ten of thousands of Korean girls and women who were forced into sexual slavery by Japan during the colonial era [1910-1945]. Referred to by the euphemism “comfort women”, those women were raped daily and lived in terrible conditions. However, their despair did not end with the war. When most came back to Korea after its liberation, they were ostracised and shamed for what had happened to them, so they kept quiet about their abuse. In 1991, almost fifty years after the end of the war, Kim Hak-sun was the first one to publicly testify against Japan and tell her story which prompted many more women to come forward and feel the relief of knowing they are not alone.

If you want to know more about the experience of Korean women drafted to sexual slavery by Japan “True stories of the Korean comfort women” by Keith Howard and “Let the good times roll : prostitution and the U.S. military in Asia” by Saundra Pollock Sturdevant are available at GWL.

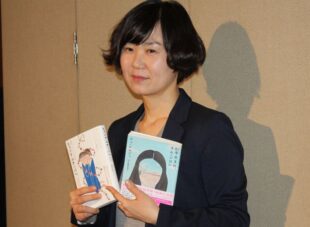

Cho Nam-joo [조남주] (1978-), feminist author

Cho Nam-joo created a new wave of discussion and awareness around the struggles faced by women in Korean society through her book “Kim Ji-young, Born 1982” [82년생 김지영]. The story is about the experience of sexism by a young mom throughout her life and the trans-generational issues it creates. From the title itself Cho Nam-joo shows that she is trying to write about the shared experience of women, choosing the name most common for a baby girl in 1982: “Kim Ji-young”.

If you are interested in the contemporary life experience of women in Korean society, the novel “The vegetarian” by Han Kang is available at GWL.

Dr. Soyeon Yi [이소연 박사] (1978-), first Korean citizen in space

Dr. Soyeon Yi loved science from a young age and achieved great academic success in that field. She was completing her Ph. D when the Korean government announce they would start their own astronaut program and one Korean astronaut could go to the International Space Station. Even though opinions around her were divided, Dr. Soyeon Yi did not hesitate to apply and, once selected, left from Russia to train. In April 2008, Dr. Soyeon Yi traveled into space, becoming the first Korean citizen to do so. Dr. Soyeon Yi is an example of determination and tenacity, and someone to look up to for every woman entering a male dominated field.

Dr. Soyeon Yi’s twitter account.

Hyeonseo Lee [이현서] (1980-), North Korean defector and activist

Hyeonseo Lee was born in North Korea, close to the border with China, almost thirty years after the separation of Korea in two countries. While her family was not poor by North Korean standards, they still struggled and witnessed the suffering around them. In 1997, Hyeonseo Lee left for China and had to live there as an illegal immigrant for ten years before defecting to South Korea. When she learnt her family was in danger in North Korea, she did not hesitate to fly back to China to help them escape and, after many hardships, finally managed to be safely reunited with them in South Korea. Hyeonseo Lee is now a human rights activist who has publicly spoken about her experience as a North Korean defector and has written a book on the subject called “The Girl with Seven Names”.

Hyeonseo Lee’s instagram account.

If you are interested by the journey of a North Korean female defector, the autobiography “In order to live : a North Korean girl’s journey to freedom” by Yeonmi Park in available at GWL.

Yuna Kim [김연아] (1990-), well-known competitive figure skater

Yuna Kim is one of the most beloved Korean athletes and one of the best female single figure skaters in history. Her nickname across various media is “Queen Yuna” due to her impressive record. Yuna Kim obtained two Olympic medals, one gold in 2010 and one silver in 2014. She has broken records and pushed the limits of her sport, leaving a legacy hard to be equaled after her retirement in 2014. Yuna Kim is also well-known in Korea for her numerous donations to charity.

South Korea and North Korea: I chose to include both “South Korean” and “North Korean” women as the separation is still a recent event and most of the women included were born before its enactment.

Name translation, order and pronunciation: The translation of names follow the most common Western usage, with most names following the Korean order of family name first (one syllable) followed by first name (two syllables). Exceptions are made due to common usage (e.g. Yuna Kim) or because some women are known by their titles only (e.g. Queen Seondeok). The Korean pronunciation of names is slowed down and accentuated to allow better comprehension for non-Korean speakers.