The Glasgow Women’s Library seems to be abuzz in the month of September with the cry of ‘Votes for Women!’. With the premiere of March on Tuesday 22nd September, and excitement for the nationwide release of Suffragette featuring Meryl Streep, the historical and cultural importance of the suffrage campaign in the early 20th century is a very relevant topic. And yet, as the Explorathon! WW1 and Women’s Lives talks at GWL on Friday 25th September will highlight, the campaign for female enfranchisement was not the only life-defining episode for women in the first few decades of the previous century.

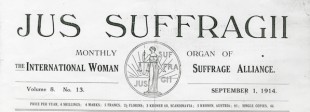

With WW1 came a social and cultural transformation that saw women’s experiences both in the family and in society altered forever. Famously, at the outbreak of WW1 the suffrage campaigns in Britain and on the Continent called a truce with their governments, but that is not to say that the goal of emancipation simply vanished. Although campaigning may have been put on hold, dreams of suffrage and the work of the different organisations still bubbled away, albeit somewhat under the surface. For example, the GWL Archive’s collection of Jus Suffragii, the monthly mouthpiece of the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) reveals attitudes within the non-militant Suffragists towards WW1 and women’s experiences, whilst still proving that there remained a collective consciousness engaged with the issue of Votes for Women.

At the outbreak of war in the summer of 1914, the Suffragists of the IWSA – including its British branch headed by Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) – were vindicated in their belief that hypermasculinity in Government and society, the historical tendency to ‘organise human society in every respect as an immense attacking body’[Rosika Schwimmer, ‘The Bankruptcy of the Man-Made World War’, Jus Suffragii 8(12) (1 August 1914)], had catapulted Europe into a inevitably bloody conflict. As the editions of Jus Suffragii following the outbreak reveal, the Suffragists  saw the war as ‘a gigantic object-lesson in the absolute failure of man’s creation, the State’ [Schwimmer, August 1914] and therefore their campaigns for women’s involvement in the public sphere were proven to remain a just cause. For if women, as the ‘custodians of human life’, and the wielders of ‘constructive forces’ had been previously granted political citizenship and access to decision making, then

saw the war as ‘a gigantic object-lesson in the absolute failure of man’s creation, the State’ [Schwimmer, August 1914] and therefore their campaigns for women’s involvement in the public sphere were proven to remain a just cause. For if women, as the ‘custodians of human life’, and the wielders of ‘constructive forces’ had been previously granted political citizenship and access to decision making, then

this power would have been used to ensure such a political reorganisation of Europe as would have rendered it certain that international disputes and grievances should be referred to law and reason, and not to the clumsy and blundering tribunal of brute force [Millicent Garrett Fawcett, ‘Message to the IWSA’, Jus Suffragii 8(13) (1 September 1914)]

This idea of women’s natural inclination for Pacifism is a driving force behind the 1914 editions of Jus Suffragii, with the achievement of Women’s Suffrage, and thereby women’s opportunity to have a voice in political discussion, presented as the means by which pacifism and peace would be realised.

Despite the global scale of the war, Jus Suffragii urged the different branches of the IWSA and its Suffragist readers to remain unaffected by violent patriotism and remain focused on the international cause of women. Universal sisterhood must be upheld, and as Fawcett remarked:

We women who have worked together for a great cause have hopes and ideals in common; these are indestructible links binding us together. We have to show that what unites us is stronger than what separates us. [Fawcett, September 1914]

The Suffragists saw Internationalism and spreading the idea that ‘women were not on the earth to hate but to love’ [‘Protest Against War’, Jus Suffragii 8(13) (1 September 1914)] as not only the means of showing the civilisation of the female sex and their campaign for political inclusion, but would act as a shining example to other women in questioning the existing male-system:

If courts are better than duels, if votes are better than pitched battles to settle national difficulties, so are international courts and international parliaments better than war. It is votes women must demand if they would abolish the horrors, the waste, the barbarism of war, and usher in the blessings of peace.[Carrie Chapman Catt, ‘Woman and War’, Jus Suffragii 8(13) (1 September 1914)]

In her ‘New Years Message to all Countries in the IWSA’, Millicent Garrett Fawcett looks forward into 1915 full of hope that the war would end and the resulting Peace Congress of Nations would place women’s rights as one of its main agendas. Poignantly overly optimistic as this message appears to us, it demonstrates the importance of the outcome of the War to the future of women’s rights and how the Suffragists saw the achievement of peace and women’s emancipation as mutually supportive:

Do the nations owe women nothing in return (for their services and sacrifices)? Are they to remain helots outside the pale of citizenship? Let us never be content with this position. Here is something which the women in all nations may begin to prepare for. Let us all set on foot steady, zealous, well-organised work to bring before the next great congress of powers the claim of women to citizenship [Millicent Garrett Fawcett, ‘A New Years Message to all the Countries in the IWSA’, Jus Suffragii 9(4) (1 January 1915)]

Join us on 25th September at 6pm for Explorathon! WW1 and Women’s Lives for a series of short talks by university researchers followed up by a Q&A session.