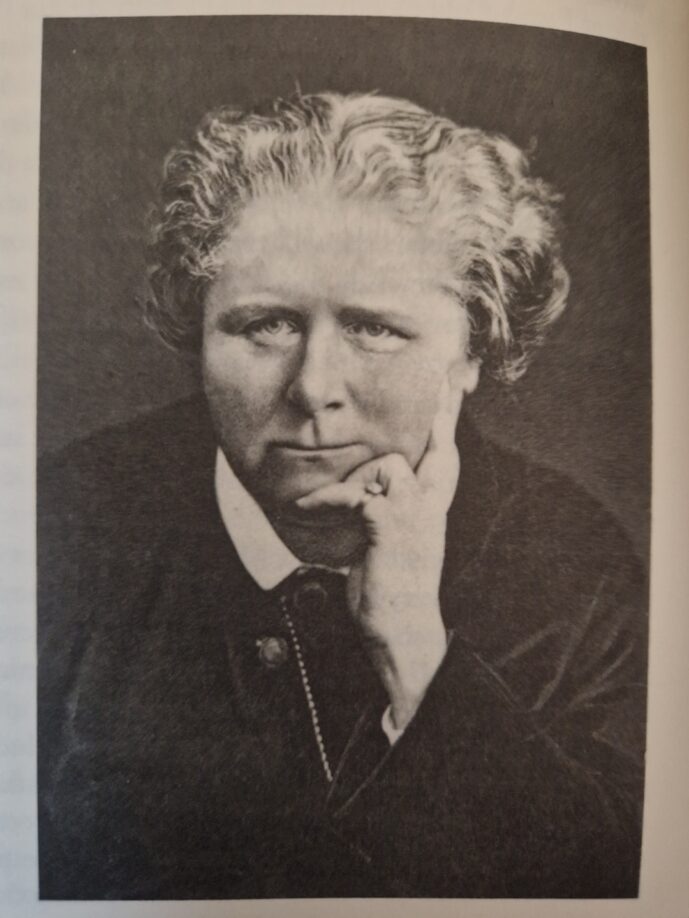

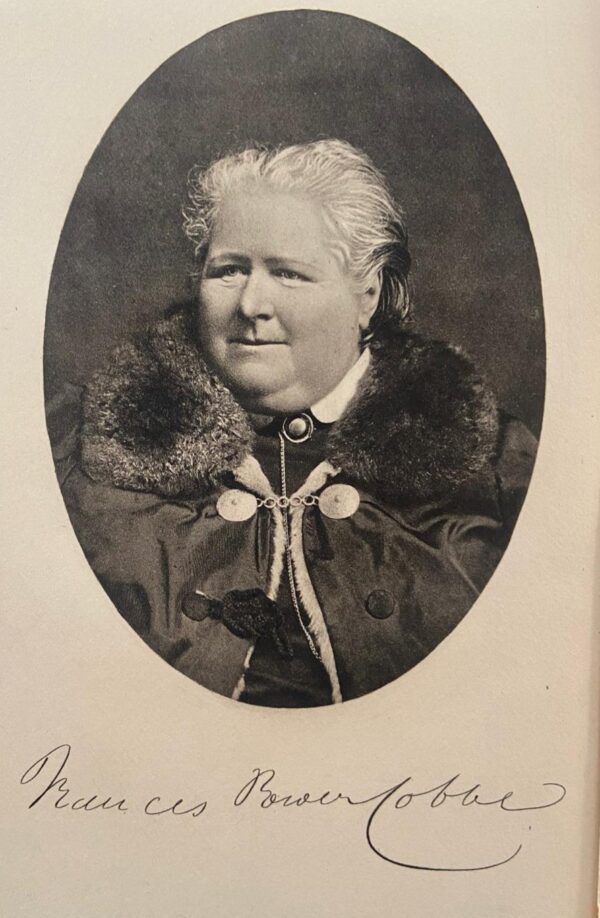

If you visit Parliament Square in London, you will find a statue of leading suffragist Millicent Fawcett. Take a closer look at the base of this statue and you will find the names and small images of other notable feminists. One of these is the Victorian-era feminist, Frances Power Cobbe, who is also my great-great-great-great aunt.

Frances has long been a figure of family folklore. Despite her appearance on the Parliament Square statue, she remains largely unknown today. Even within my family, knowledge of her is at best hazy. And so, I decided to find out who she really was. I began expecting to find an interesting woman who wrote occasionally. Instead, I was astonished to find a hugely prominent feminist and social reformer who used her position as a journalist to become what I can only describe as one of the most influential female political figures of her time. Her work was of such magnitude that, in some instances, it directly influenced policy and changes in law to protect women’s rights. I discovered a vibrant character, a force of nature, who did not shy away from addressing some of the most embedded social norms of the Victorian era, unflinchingly challenging the inequalities, dangers, and deprivation faced by women at the time.

I had to dig deep to find substantial information about her work and life. Luckily, I was able to find her autobiography from 1894, and some niche academic books published around 20 years ago, helping me to form a fuller picture of who she really was. Apart from this she seems to have been mostly forgotten in the history of feminism.

Born in Dublin in 1822 and dying in Wales in 1904, her life and career spanned the height of the Victorian Era. Coming from Anglo-Irish gentry, she was from a privileged and well-educated background.[1] She lived most of her life with her partner, Mary Lloyd, in England and Wales.

Writing prolifically for a variety of newspapers and periodicals, she became one of the only women at the time who actually made a living as a journalist writing for the mainstream commercial press, which was highly influential in Victorian society.[2]

She was insistent on the political nature of her writing and successfully managed to forge a career in a typically male dominated public arena.[3] Within a society that largely confined women to domestic life, denied them the vote and restricted their access to opportunities for education and occupations available to men, Frances used her journalism to argue for, and help enact social change, promoting women’s rights into the forefront of Victorian culture. Although, in her autobiography, she says that she wishes she was a man so that she could enter Parliament and create real change,[4] she didn’t let her exclusion from the systems of representative democracy stop her. Describing herself as a ‘women’s rights woman’,[5] she acted on what she saw as fundamental issues facing women such as the campaign for women’s suffrage and acting against domestic violence.

How was Frances such a prominent figure in Victorian life and yet barely heard of today?

Although she has been named alongside, and regularly corresponded with, famous contemporaries such as Charles Darwin, William Gladstone, Louisa Alcott, Mary Carpenter, and Millicent Fawcett (to name a few), she seems to have been largely neglected by history.

There are numerous reasons that may explain why she has been forgotten. First, as Susan Hamilton explains in her biography, Frances’ kind of writing, being in the mainstream periodical press, has not been the subject of much research.[6] Another explanation is that she did not write fiction,[7] which was regarded as a more acceptable, or “feminine” occupation. And so, unlike novelists such as Louisa Alcott and Ellen Wood, her work has not survived.

The central reason may be the overshadowing of her work by the ‘dramatic’ campaign of the suffragists and suffragettes of the early 1900s.[8] If you say the word feminism today, many people may first think of women such as Emmeline Pankhurst and the militant campaign for the vote. This movement is often seen as the pinnacle of the 1st wave of feminism in Britain. This overshadowing, says Sally Mitchell, is what led to Frances’ work becoming ‘obsolete.’[9]

However, I think it’s mistaken to say that Frances’ work became outdated. Her work was actually very far ahead of its time in several areas. Apart from her feminist work, in the 1870s she became the leading figure in the British anti-vivisection movement, instrumental in passing the first Cruelty to Animals bill. She was at the forefront of the early Victorian women’s suffrage campaign, becoming one of the first members of the executive council of the Central Committee of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage in 1871.[10] This Committee was a body that represented other regional groups such as those in Manchester and Edinburgh, bringing the suffrage campaign to the centre of UK political life, focussing its efforts on lobbying the UK Parliament. They seem to have been somewhat successful as, from the early 1870 – 1880s, debates on women’s suffrage were held every year in the House of Commons,[11] although, of course, legal change wasn’t achieved for another 50 years. At the very ‘heart’ of this movement,[12] Frances therefore directly contributed to ensuring that it was prominent in Victorian politics.

Aside from this work to include women in the public or political sphere, what I find most outstanding is her championing of women’s rights in domestic life, particularly regarding domestic violence. The movement to improve the private life of women suffering domestic abuse is typically recorded in the 2nd and 3rd waves of feminism in the 1960s to 1990s.[13] However, around 100 years before this, Frances was a trailblazer with her paper ‘Wife Torture in England’ which directly influenced the passing of the Marital Causes Act 1878. This Act allowed for women to divorce their husbands on the grounds of domestic violence and provided for protection orders for women from their abusive husbands. A 2016 parliamentary debate on the provision of women’s refuges highlights this huge time gap. Labour MP Julie Cooper said that Frances’ writing on domestic abuse moved the then Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli to tears.[14] She goes on to say that ‘nothing of substance’ happened again until the 1970s, emphasising just how pioneering Frances’ work was.

Frances Power Cobbe, this prominent, prolific, and trailblazing feminist, should be remembered today, using her own words, as a truly great “women’s rights woman.”

[1] Frances Power Cobbe, Life of Frances Power Cobbe, 1894, p.17

[2] Sally Mitchell, Frances Power Cobbe, Victorian Feminist, Journalist, Reformer, 2004, p.2

[3] Susan Hamilton, Frances Power Cobbe and Victorian Feminism, 2006, p.22

[4] Frances Power Cobbe, p.2

[5] Frances Power Cobbe, p.26

[6] Hamilton, p.2

[7] Mitchell, p.3

[8] Mitchell, p.3-4

[9] Mitchell, p.3-4

[10] https://spartacus-educational.com/Wcentral.htm

[11] UK Parliament, ‘Early Suffragist Campaigning’ GET LINK

[12] Mitchell, p.326

[13] For example see Harriet Dyer, The Little Book of Feminism, 2016

[14] UK Parliament debate, Domestic Violence Refuges, Volume 609: debated on Wednesday 11 May 2016, Hansard https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2016-05-11/debates/16051141000001/DomesticViolenceRefuges?highlight=transgender