The Glasgow Women’s Library champions the voices of women who, for various reasons, haven’t been, or aren’t being, heard. Whether that’s refugees coming to Glasgow in the hope for a more stable life, or Suffragettes who played crucial roles in campaigns but faded into obscurity, or the thousands of other voices that the library carefully showcases. The branding of the GWL couldn’t be clearer: women’s voices will be heard here.

But what about those women who don’t have any concrete traces left? The women that we know existed, but we can’t evidence their lives. Exhibits, books, and presentations (all of which the GWL puts on regularly) rely on the existence of primary materials. As a historian, I shudder at the idea of trying to write or present a paper based on little to no evidence. My reputation as an academic relies on my ability to find primary evidence and extrapolate from there, backing up everything I say. It becomes immensely frustrating when I have a hunch about something but there’s nothing in the sources to say I’m right (this happens more often than I’d like to admit).

My research looks at masculinities present at Scottish universities between 1560 and 1610. As my focus is on universities, which were exclusively male (with women pretty much banned from university grounds), most of my research and writing deals with men. But men don’t magically appear out of nowhere, and they don’t exist in a vacuum. The majority of men in the early modern period got married and had children: these things required (for the norms of the time) a woman. Also, because of patriarchy and sexism, it was a woman (the ‘lavender’) who did the washing of the masters and students. So, there were definitely women around, whether they were present in the sources of not!

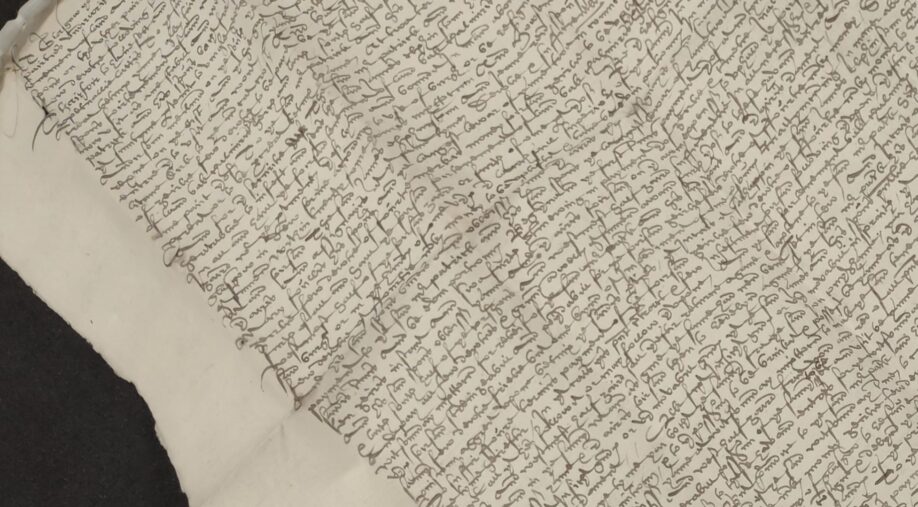

![A part of a manuscript from the Balcarres Papers held by the NLS, 'the common lavendar [washerwoman]' is highlighted.](https://womenslibrary.org.uk/gwl_wp/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/fo.185r-Adv.MS-29.2.7-918x521.jpg)

I know some of their names and parts of their stories. Mary Foulis was the wife of Patrick Scharp, who was the principal of the University of Glasgow (shoutout to Glasgow). She was a witness to receipts of land transactions whilst her husband was working at the university. William Welwood was a master at the University of St Andrews who fled to his mother’s house when he was being attacked (during a very intense feud with the family of another master) – other sources about Welwood show that he was close with his mother and that she lived in a property rented from the university. Similarly, Homer Blair (another St Andrews master) noted in a letter to the king that his mother had supported him throughout his career and now he needed to support her as she was unwell. Although Andrew Melville (famed theologian who taught at Glasgow and St Andrews) never married, he had plenty of opinions about his nephew, James, marrying again, arguing that he shouldn’t marry a young rich heiress as he had grown children and needed to conduct himself with dignity.

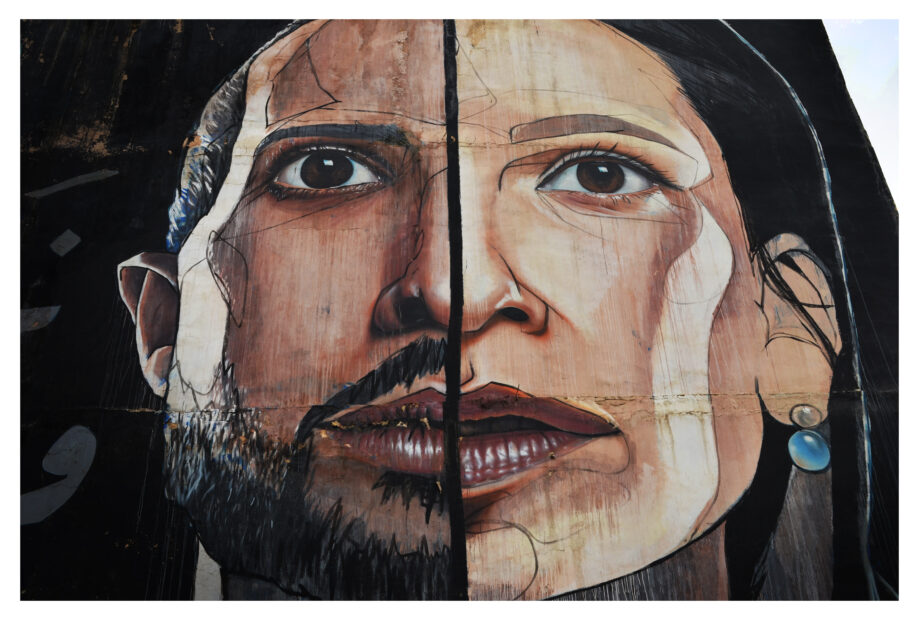

Most of these stories are hints or brief mentions. Often the same is true for the men of this period – so many sources don’t survive or are fragmentary. But the women in this period obviously come off much worse. Not the main movers and shakers in a politically fraught and religiously tense period, they are relegated to the background, with little overlap with the universities or the big-picture politics of the kirk. As a woman myself, I find this incredibly disheartening and frustrating. I can’t help but wonder what it would be like if my existence was obscured, faded, and forgotten about. All of my day-to-day experiences, my hopes and ambitions, my achievements not recognised, whilst (likely) those of my husband would be praised and remembered, and I would just be known as ‘the wife of’ (I am shuddering as I’m writing this).

Luckily, I think I can avoid such a fate. But there are millions of women who did not. How do we celebrate these voices and reconstruct their lives with so little (or even nothing)? I think this is where creative practices can come in. As a historian I pride myself on detail and creating historically accurate narratives, but this doesn’t have to preclude the use of imagination in creating stories. We can use the facts that we have to build a realistic world, which we can then shape to include those forgotten or unrecorded voices. Plays, novels, poetry, TV, film, song…the mediums are endless for creating these narratives. And indeed, this subject is one that is becoming more mainstream. More and more media focusses on imaginary women in true events, or on women we know very little about. Granted, I do wish sometimes that TV and films in particular weren’t so reliant on tropes and bad writing, but the movement is happening.

Maybe this could be the theme of some GWL workshops in the future. GWL already is ahead of the game in housing lots of items from ‘ordinary’ women’s lives, from sewing patterns to magazines to diaries. These, perhaps, could be the focus of some imaginative practices. We could have some creative sessions where different people pick an obscure historical woman – or an object of such a woman – to focus on and create a story about in whatever medium they choose. No queens or ‘exceptional women’ here. No Elizabeth Is or Cleopatras or Florence Nightingales. Instead, we’ll imagine so-called ‘ordinary women’ living their lives and, for the first time in a long time, being thought as more than just ‘the wife of’.