As I embark on my PhD at the University of Glasgow – looking at masculinities within early modern universities – I have been ruminating on processes of learning and thinking about what (outside of school) is available to us to help increase our education levels and knowledge. I think this is partly prompted by the fact that my PhD is about education: what students (who could be as young as 12 back then) learned, how they were taught, and what kind of men they became as a result. It’s also prompted by my volunteering at the GWL; which is a multi-level learning environment for all kinds of people of all ages.

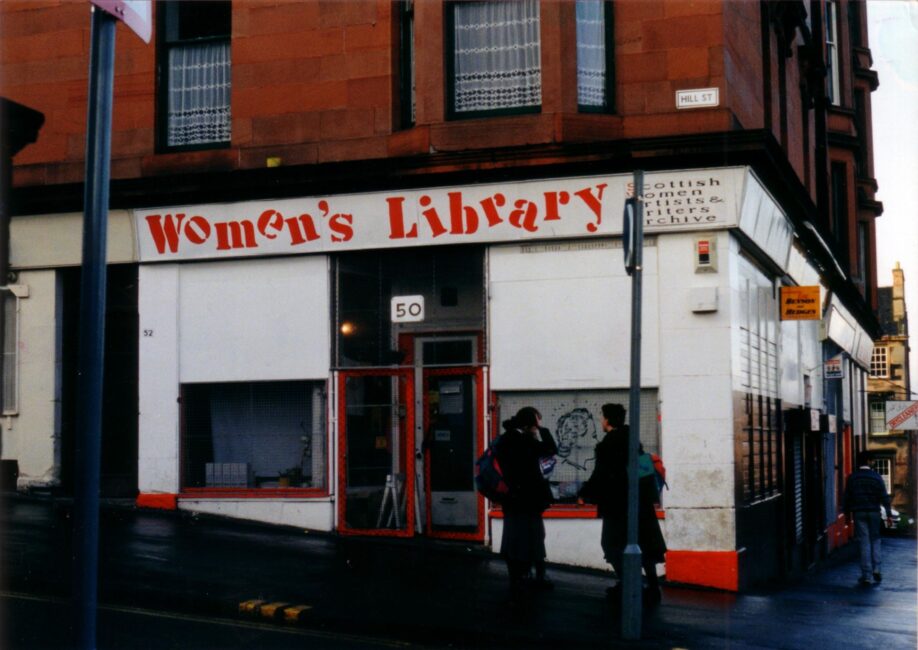

I volunteered for the Open Doors festival at GWL recently and a couple of wee kids came in with parents in tow looking for books – they were so excited and happy to see the different kinds of children’s books we have, and the mum informed me that they are regulars. I was struck by how the kids were so keen to read and have new experiences; children are like little sponges ready to soak up all kinds of information (my wee sister recently asked me how digestive systems work and was super excited for all the gruesome details). I stood there thinking about how the GWL is the perfect place to encourage that love of learning. In fact, learning and education are at the heart of what GWL does. Its very foundations are steeped in a desire to not only give women in Scotland more opportunities to access different types of knowledge, but also in its proactiveness for educating people about Scottish women and women’s history in general.

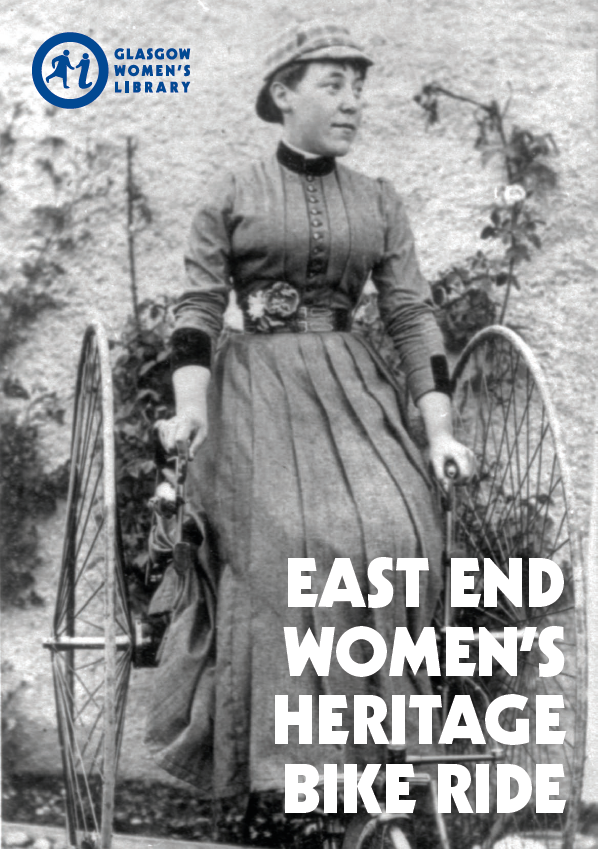

Book clubs, heritage walks, tutoring women, encouraging university-level research, having a huge range of books for anyone to enjoy, running a wide variety of events, working with schools, allowing external companies to come in and use the space, having a popular blog (wahey!)…these are all hallmarks of the GWL approach. Every single one of them is intrinsically linked to learning and inspiring people to increase their knowledge about different subjects. Even the physical space that the GWL is housed in is intrinsically linked to a learning environment, as the building was originally built to be a library in the early 20th century – if you’re visiting, make sure to check out the ‘Boys and Girls’ sign on the side of the building where the children’s entrance was!

So, what does this have to do with Mary, Queen of Scots? Well, although there is plenty I could say about her political choices (poor), her choice of husbands (terrible), and her obsession with being queen of France, England and Scotland (let’s not get into that), her relationship with learning and education is fascinating. And as I have written about other famous Scottish royal women, I thought it time that I dedicate some space to the most famous of all.

Mary, Queen of Scots was born into a difficult situation. Her father died almost immediately after she was born (apparently upon hearing that she was a girl instead of the wee boy prince he wanted, he shuffled off this mortal coil in disappointment) and her French mother had to rule the cantankerous Scots as regent in the infant queen’s name. Add an unpopular French betrothal to the Dauphin, high taxes to pay the French troops defending Scotland, Mary’s claim to the English throne, a Reformation, and wars with England into the mix, and you have a powder keg ready to go off at any given moment. Now, some of this was expected and some of it absolutely wasn’t. So how do you prep someone for this life-defining, and potentially life-threatening, role?

The answer is…you guessed it, a good education! Mary was sent to France at four years old (you might remember she was sent with several other girls called Mary which everyone thought was very amusing) in order to be brought up with her future husband (the French Dauphin) and his family, which was one of the most powerful royal families of the time. Now, when Mary was sent to France, everyone assumed that Mary would marry Frances (the Dauphin) and, with her husband, succeed her father-in-law when he died as King and Queen of France and Scotland. Scotland was to become part of the French ‘empire’, shown through the King of France getting Mary to sign secret clauses before getting married (potentially forcing her to do so), saying that if she died with no children then Scotland would automatically be under the French king’s jurisdiction. So, for all intents and purposes, Mary was brought up and educated to be Queen of France, not necessarily Queen of Scots. Everything the King of France had negotiated had been to absorb Scotland into his Franco-empire. Of course, life doesn’t always go to plan. One jousting accident later, the King of France was dead. Just over a year later, his son (Mary’s husband) was also dead. And Mary arrived back in Scotland at the tender age of nineteen, to a country that had changed significantly from the one she had left; one that she didn’t really remember anyway. Most importantly, it was, arguably, a country that she hadn’t been educated to rule.

A lot of effort had been put into making sure that Mary received top-notch tutoring (in languages, music, writing, embroidery – everything a young queen needs) and that she was kept informed of what was happening back in Scotland (if everything had gone to plan, its assumed that she would have mostly resided in France but would have still needed to know what was happening in Scotland). She was a keen reader and loved music – the preacher John Knox criticised her later in life for loving music and dancing too much (he was a bit of a killjoy). When she came back to Scotland, she made sure that the Scottish universities had funding and fostered a culture of learning (shoutout to Scottish women encouraging a love of books!). Mary had her own household from an early age – almost bankrupting her poor mum back in Scotland – and was treated as the future Queen of France by everyone. This all meant that when the time came, Mary would know exactly what was expected of her in her role, such as interceding on behalf of criminals, managing different estates, setting the tone at court, and supporting her husband, all while performing the important job of bearing royal babies.

I’m not a Mary-sympathiser. I think she made a lot of poor decisions as Queen of Scots and when she was a captive of Elizabeth I (pro-tip: don’t plot to overthrow the person who has imprisoned you and can execute you at any time). However, I do think that she was dealt a terrible hand and that, despite all the negotiations and planning, ultimately the adults in her life failed to prepare her for the role she ended up being thrust into. Being Queen of Scots was hugely different to being Queen of France. And, whilst I stand by my opinions about her, I do think that she should be viewed with sympathy for how challenging her job was; she wasn’t given the right tools to do the job she needed to do.

Which brings me back to the power of learning. The right education can make a world of difference to someone’s life. If I hadn’t had the opportunity to go to school and university, I wouldn’t be doing my PhD just now. Maybe if Mary had been given the opportunity to learn the skills she needed, she might not have ended up executed, having spent 19 years in exile. During a time when the Arts are being defunded and ridiculed, costs are going up, and people ask what the value of cultural spaces are, I think it’s important we remember that learning makes a difference. GWL makes a difference. Hopefully those wee kids I saw recently at the library keep their love of books for years to come.

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.