Part 2: Women Spies, Accuracy, and Authenticity

Hello, dear readers! My name is Carly, I’m an English literature and linguistics student from Germany and I’m currently in the library as part of a four-month student placement. When I’m not getting side-tracked by all the amazing things to be found in the GWL archive, I’m mostly busy cataloguing and listing materials, writing blogs and helping with the preparations for GWL’s 30th anniversary. Hopefully, you’ll see more of me and my attempts at (somewhat creative) writing in the weeks to come!

Hello friends, fans, and enthusiasts of historical fiction and welcome back!

If you’ve read my last entry on this topic, you’ll know that this blog is about history. But not the kind of history taught in school or found in the kinds of tomes that you used to doodle on while tuning out the voice of your history teacher. Nah-ah. Here, we’re pondering and tackling some of the fundamental questions and issues to do with stories about the past that are personal, vivid, immersive, and – admittedly – also a teensy bit invented, to varying degrees. We are talking about novels that tell the stories of real historical figures, of invented figures living through historical events, or of modern characters travelling back in time – be it through a magical stone circle, a genetic disorder, or through an ancestor who keeps calling one back to his time because he just cannot grasp the concept of not almost getting himself killed on a regular basis. More specifically, this blog series is about works of historical fiction which try to shed light on the experience of people whose lives and contributions have been forgotten or ignored for a long time in favour of those of straight, old white blokes.

The Road So Far: Hidden Figures and the Fact/Fiction Debate

You might have noticed that recent years have seen an increasing interest in historical counter narratives and the rediscovery of minority and overlooked histories including women’s stories, not only within academic circles but in mainstream pop culture as well. In my last blog entry, I addressed what I termed the “fact vs fiction” debate – the general disagreement among scholars and mainstream audiences alike regarding the extent to which a creator of a work of historical fiction should be free to take creative liberty by twisting or distorting what we know as historical ‘facts’. Should they stick only to what we know truly happened, or should they do things a bit more Gandalf-style, following the motto that “all good stories deserve embellishment”?

Taking a closer look at the 2016 movie Hidden Figures about African-American women computers working for NASA during the so-called ‘space race’ in the mid-twentieth century, I discussed one of the downsides to such embellishment, namely when it introduces tropes or fictional characters that help maintain and keep alive the exact same oppressive structures that the creators of these works of historical fiction are aiming to denounce. In Hidden Figures’s case, it was the trope of the “white saviour” – a white character who does not seem to have any other function within the story other than to sweep in and save the day, thereby often distorting the actual reality of the historical time depicted and downplaying the extent of prejudice and discrimination experienced by the protagonists. At the same time, the trope seems to suggest that the people depicted – be they from ethnic minority backgrounds, the LGBTQ+ community, or from any other group that has experienced oppression and discrimination – are in need of someone else to protect them, rather than being able to stand up for themselves.

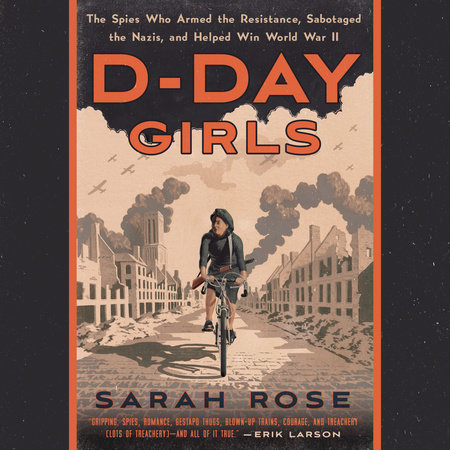

Female Spies, D-Day Girls, and Fiction in Non-Fiction

In today’s blog entry, though, I’m tackling different historical events as they have been depicted and fictionalised by both authors and filmmakers: the female agents of the so-called Special Operations Executive (SOE for short), a secret agency that Winston Churchill tasked with the support of resistance movements in foreign countries during World War II. The 55 women deployed to France and other countries were an important asset to the agency since – unlike men – they could travel freely as they were not expected to work during the day and were considered to be more inconspicuous than men (here’s one of the very few good things resulting from gender stereotypes, hooray!).

Let’s start with Sarah Rose’s D-Day Girls, one of the many non-fiction accounts and biographies about the SOE women. Now, if you’ve been paying attention, the last sentence might have made you pause and think something along the lines of “hold on a second – non-fiction? I thought we were talking about historical fiction here?” You’re right! However, while D-Day Girls most certainly cannot be categorised as historical fiction, it is relevant to this blog because, despite its classification as a biography or memoir, Rose’s book has sometimes been accused of unnecessarily dramatizing and fictionalising events. Interestingly, these accusations can be found alongside reviews praising the author for her extensive research: she even went so far as to move to France, learn French, go parachuting and study Morse code in order to be able to fully understand and authentically depict her heroines’ lives and experiences. The book’s focus lies primarily on these women – the entirety of her final chapter is dedicated to sexism in WWII, denouncing the unequal treatment of the female SOE spies compared to their male counterparts. As the author herself notes, after the war

Sarah Rose in D-Day Girls

“[m]ale agents performing the same tasks might be recommended for the Victoria Cross, created by Queen Victoria, the highest honor for military gallantry. While Corps Féminins did much of the same work in the same places, they were not technically soldiers and so not eligible for military honors — only civil decorations … Their salaries and ranks were lower; so too were their war pensions.”

When scrolling through the reviews of D-Day Girls on Goodreads, it becomes apparent that those rating the book 2 stars or less are largely in agreement about what they did not like about it: the narrative, they say, is too focused on the heroines’ love lives and affairs. As one reviewer complains: “until the end of the book, you don’t actually know how the agents helped the D-day operation but just know they married with different male agents.” The book’s focus, they seem to suggest, should be less on love stories and relationships and rather on the suspenseful adventures and important achievements of these women. Another user claims: “She [Rose] takes the lives of real men and women and dramatizes them to the point where they cease to have been real, but are now fictional heroes and heroines.” This seems to be something many users agree with – one reviewer comments: “Unfortunately, the author often mixes up fact, speculation, and opinion, without really separating the three. She narrates the story and tells what the characters are thinking and feeling as if they absolutely thought and felt those things, despite there being no evidence for it.”

What we are dealing with here, then, seems to be an instance of non-fiction that, in its effort to provide a read that is equally informative and entertaining, does not always manage to balance the two, at least according to some reviewers (and that opinion is certainly not shared by every reviewer!). Of course, the moment we start trying to create a suspenseful, gripping, and entertaining reading experience, we are forced to create a narrative, a story. A mere enumeration of facts à la “first A happened, then B followed by C” surely won’t have anyone binge-eating their body weight in popcorn because they can’t deal with the nail-biting, unbearable suspense. No one’s probably ever cried about mere years and dates either. It’s a thin line that anyone writing a book about history for non-academic audiences will be forced to walk: you want to tell the true story of your object(s) of research, yet you (and your publisher) would probably also appreciate it if people actually ended up buying, reading, and enjoying what you wrote.

History-Writing and the Issue with Narrative

The question is: are we still speaking absolute truth once we have started narrativising events? We order these events we are writing about, label some as more significant than others, highlight some and downplay others, and we assign them causal relations, sometimes ending in what is generally termed the “post hoc ergo propter hoc” fallacy (yes, I’m bringing in the big guns here). The phrase roughly translates to “since event Y followed event X, event Y must have been caused by event X” and denotes the mistake of thinking that one event was caused by another, only because they occurred subsequently. We’re establishing causality where there might never have been any to begin with merely because it seems to make sense in hindsight. All of these processes involved in the narrativisation of historical events and facts are an essential part of the creation of historical narrative. This, however, is not to say that history as we tell it is nothing but a lie neatly wrapped in academic jargon. The different fallacies involved in history-writing can of course be circumnavigated to varying degrees, and some events Y simply happen to have been caused by certain events X, full stop. What I’m trying to highlight in my little detour here, though, is that, when judging a book about historical events or persons, we’d do well to remember that even the most fact-based history-writing unavoidably includes at least some of the processes named above and, unfortunately, it is likely we will never know for sure if the author got it completely right, unless, of course, Doctor Who decided to park his TARDIS right outside our front door tomorrow and let us take it for a spin.

I chose to start with this particular biography to show you how the fact/fiction dilemma is far from limited to historical fiction – and deviations from historical ‘fact’ seem to be especially enraging when these books are advertised as purely non-fictional, which – really – shouldn’t come as much of a surprise.

City of Spies: Authentic, Accurate, or Both?

Churchill’s (female) SOE agents, however, also inspired several works of historical fiction, one of which is Mara Timon’s City of Spies, which revolves around the story of fictional SOE agent Elisabeth de Mornay who poses as a wealthy French widow in Lisbon to infiltrate a German espionage ring. Interestingly, one of the first reviews of the book on Waterstones’s website praises the novel for being “a perfect blend of fact and fiction [which is] loosely based in[sic] some of the real events that happened in Lisbon on [sic] 1943.” Similarly, many other comments repeatedly highlight the “authenticity” of Timon’s writing.

What is meant by that, though? What makes Timon’s novel “authentic” in the eyes of readers, most of whom are likely not to be particularly well informed about the historical facts and circumstances surrounding the author’s chosen topic, and what do these reviewers mean when they call it “authentic”? That Rose stuck completely to historical facts? Or, more likely, is it that the novel ‘feels’ realistic in its depiction of the protagonist’s reality when compared to the knowledge readers already have about espionage and WWII? Let’s delve a little deeper into that particular question.

In an article for Rethinking History, Laura Saxton suggests that we should make a distinction between “accuracy” – “the extent to which a text’s representation is consistent with available evidence” – and “authenticity” – “the extent to which readers believe that a representation captures the past”. Authenticity therefore reveals itself to be something that is highly subjective: it’s about what feels real, rather than what we know to have been real. And while authenticity and factual accuracy may go hand in hand in many cases, they don’t necessarily have to. An author can manage to capture a certain feel of the past, bringing to life the sounds, smells, and general atmosphere of a time that is long gone, while at the same time tampering with the order of events, the people involved, or something else entirely.

Mara Timon, author of City of Spies, tells us that „[a]fter binge-reading [the female SOE agents’] stories, [she] became determined to write about them, or rather, fictional accounts of fictional agents, but staying as close to the history as [she] could.” Cleverly, she reminds us that her novel is fiction, first and foremost – fiction which is based on history but remains fiction nonetheless. Like most other historical writers these days, she does not claim to have depicted the truth. By telling us about the act of “binge-reading their stories”, though, she simultaneously legitimises her writing, letting us know that she has done extensive research and bluntly telling us: “I know what I’m doing!” It’s a strategy that most historical novelists seem to prefer, assuring us that they’ve done the best they could to stick to historical facts, yet have taken creative liberty when there were ‘gaps’ to fill or when it was necessary for the sake of story coherence.

What Makes the Novel Authentic?

When starting to read an historical novel, the reader is thus aware – to some extent, at least – of its partly fictional elements. How come that we still end up seeing it as ‘authentic’ despite our knowledge of its straying from commonly accepted historical narrative? In the case of City of Spies, the inclusion of historical figures and events alongside its fictive protagonist seems to have been essential for the novel’s feeling of authenticity. As one reviewer writes: “I particularly liked the inclusion of real figures and events from the time, which helped to anchor the plot in its setting.” Adherence to very general and major historical facts also seems to be important, as many reviews suggest. ‘You can change minor details but don’t mess with the overall chain of events!’, seems to be the motto here. At the same time, conveying emotions and feelings we think must have been experienced by the actual historical figures depicted appears to be similarly essential, such as the “paranoia […] in wartime Portugal” and the “massive amount of uncertainty” and “danger” of the times.

A question that remains, though, is to what extent readers can distinguish between what is accurate and what is authentic during the reading experience. Something can seem highly authentic while being completely made up at the same time – are readers able to make that distinction? And what if a novel’s factual inaccuracy is not obvious or addressed in an author’s note? Of course, we could insist that fact-checking should be the reader’s responsibility – after all, fictional elements in a work of historical fiction should not come as a surprise, meaning that readers should be able to not take everything they read at face value. But hand on heart: do you always start fact-checking after reading an historical novel? Do you usually start googling, or reading academic literature on the topic, or, if we’re being honest, do you sometimes just let the novel do its magic? And what if you did? What could possibly be problematic about that, especially when we are talking about the history of formerly oppressed or discriminated groups? This might also give us an explanation as to why some people seem to be enraged by deviations from known historical narrative. That’s a question I’ll leave you to ponder for the time being, hoping that you’ll come back to see what answers I’ve come up with in next week’s entry on the topic.

If you’re interested in the topic of historical fiction, don’t forget to read my last blog entry on the topic and to have a look at all the great novels GWL has to offer, such as: Kindred by Octavia Butler, which incorporates time travel and aspects of slave narratives, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Hilary Mantel’s famous Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, which are set in the Tudor era, or Alice Jolly’s Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile about an elderly maidservant at the end of the 19th century. Come visit the library or explore our online catalogue for some inspiration!

Sources:

Galuppo, Mia. ""New Female Spy Films Look to Go Beyond Bond." The Hollywood Reporter, 2 November 2017. Image.

"Hidden Figures." Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hidden_Figures. Image."Reviews: City of Spies" Waterstones, https://www.waterstones.com/reviews/city-of-spies/mara-timon/9781838770709/order/_votes/page/3. Accessed 7 September 2021.

Rose, Sarah. D-Day Girls: The Spies Who Armed the Resistance, Sabotaged the Nazis, and Helped Win World War II. Penguin, 2019.

Rose, Sarha. "D-Day Girls: The Spies Who Armed the Resistance, Sabotaged the Nazis, and Helped Win World War II" Amazon, Accessed 10 September 2021. Image.

Saxton, Laura. "A True Story: Defining Accuracy and Authenticity in Historical Fiction." Rethinking History, vol 24, no. 2, 2020. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13642529.2020.1727189?journalCode=rrhi20. Accessed 7 September 2021.

Timons, Mara. "City of Spies: Shortlisted for the Specsavers Debut Crime Novel Award." Amazon, Accessed 10 September 2021. Image.