This is the second post in a three-part blog exploring the history of feminist housing activism in the 1970s and 1980s. Following on from yesterday’s post on the feminist squatting movement, this blog explores feminist efforts to shape the world around us by pooling our skills, labour and resources into co-operative building and design.

A home of our own

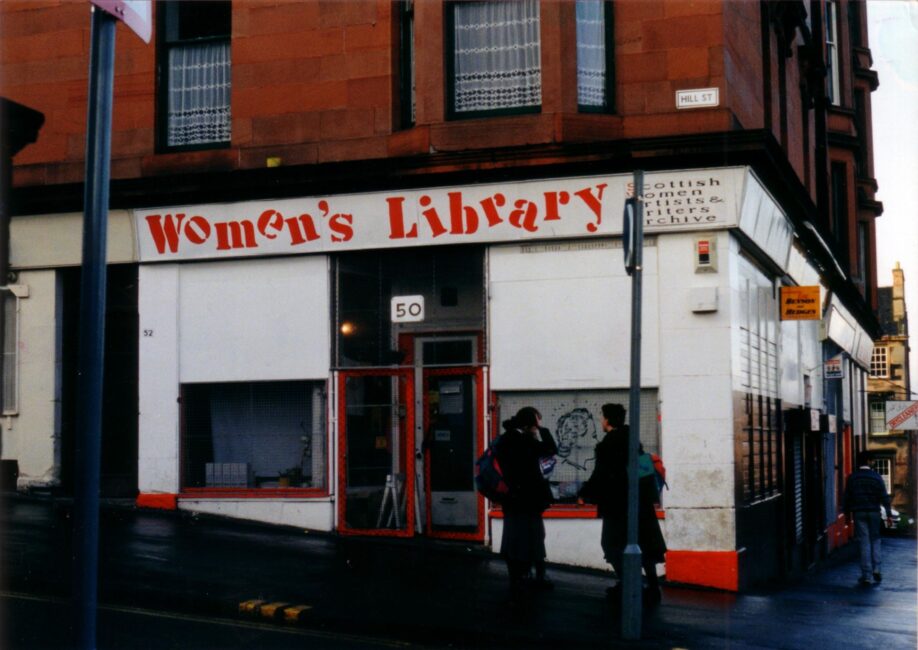

Along with women’s centres and feminist enterprises, another offshoot of the feminist squats of the 1970s and early 1980s was a cluster of architectural and construction co-operatives. In 1978 the Greater London Council declared an amnesty for squatters, granting some of them leave to remain in their properties on the condition that they fixed them up and paid nominal rents; other regional councils would soon follow this model. Many squatters began teaching themselves to plumb, wire and structurally repair their squatted houses – pursuits which, once started, forced them to grapple with how patriarchy quite literally shapes the spaces where our lives play out. It wasn’t long before some of the women who had embarked on this – among them architects, artists, and builders – collectivised to begin developing feminist practices of designing, building and maintaining women’s spaces.

Established in 1980, Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative is one of the more famous of these collectives. What started as a discussion group amongst women who had broken away from the New Architecture Movement, a heavily male-dominated coalition of radical architects, blossomed into a book project and later, an architectural practice and Community Technical Aid Centre (CTAC). Julia Dwyer and Jos Boys, two early members of Matrix, were both a part of the squatting communities thriving in Kennington and Islington respectively. In an interview with Christine Wall, Jos Boys explains what the squatted house she shared with builders, painters and other architects meant for Matrix:

Squatting meant that I had access to this other space that was free and was very easy to rent, and so we used to have our meetings there, and Matrix, both the practice and the book, grew out of it.

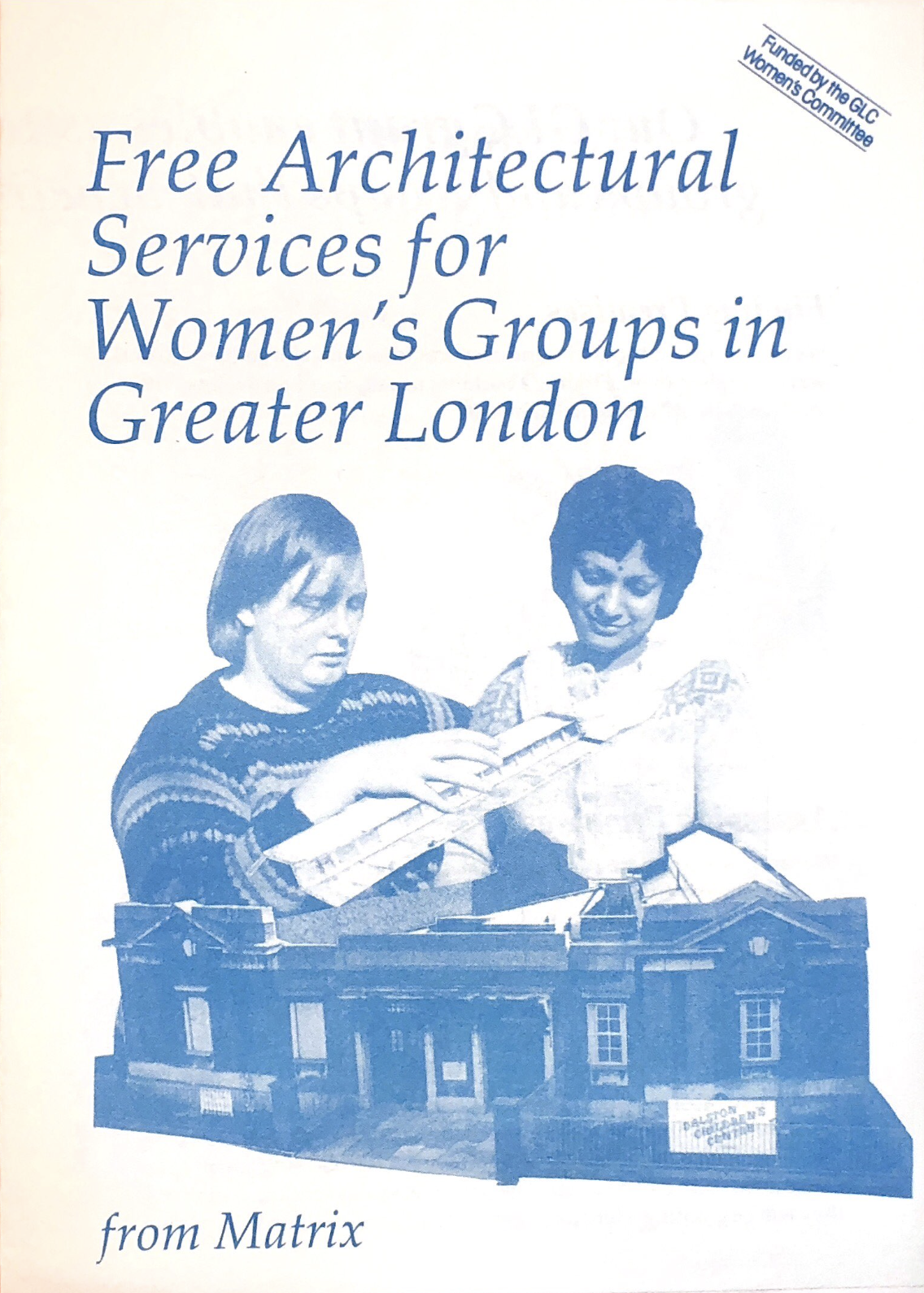

From these early meetings at Jos’s house came the landmark book Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment (1984), a feminist critique of the male domination of modern architecture. As a collective, Matrix worked solely on community-led social enterprises including women’s centres, LGBT housing projects, and childcare hubs. Grant funding from the Greater London Council, and later from individual borough councils, enabled Matrix to provide free advice, guidance and feasibility studies for non-profit organisations like Camden Lesbian Centre & Black Lesbian Group (CLC&BLG), along with organising educational programmes and workshops designed to make architecture and construction more accessible career paths for women. For CLC&BLG specifically, Matrix ran several workshops and offered regular consultation throughout the Centre’s hunt for premises, surveying potential sites to see how they matched up to the group’s brief. Matrix developed a mode of working which placed the client’s needs front and centre of a building project, beginning any brief by asking what happens in an average day in the building, how access requirements are factored into its design, and how the building should feel to its community.

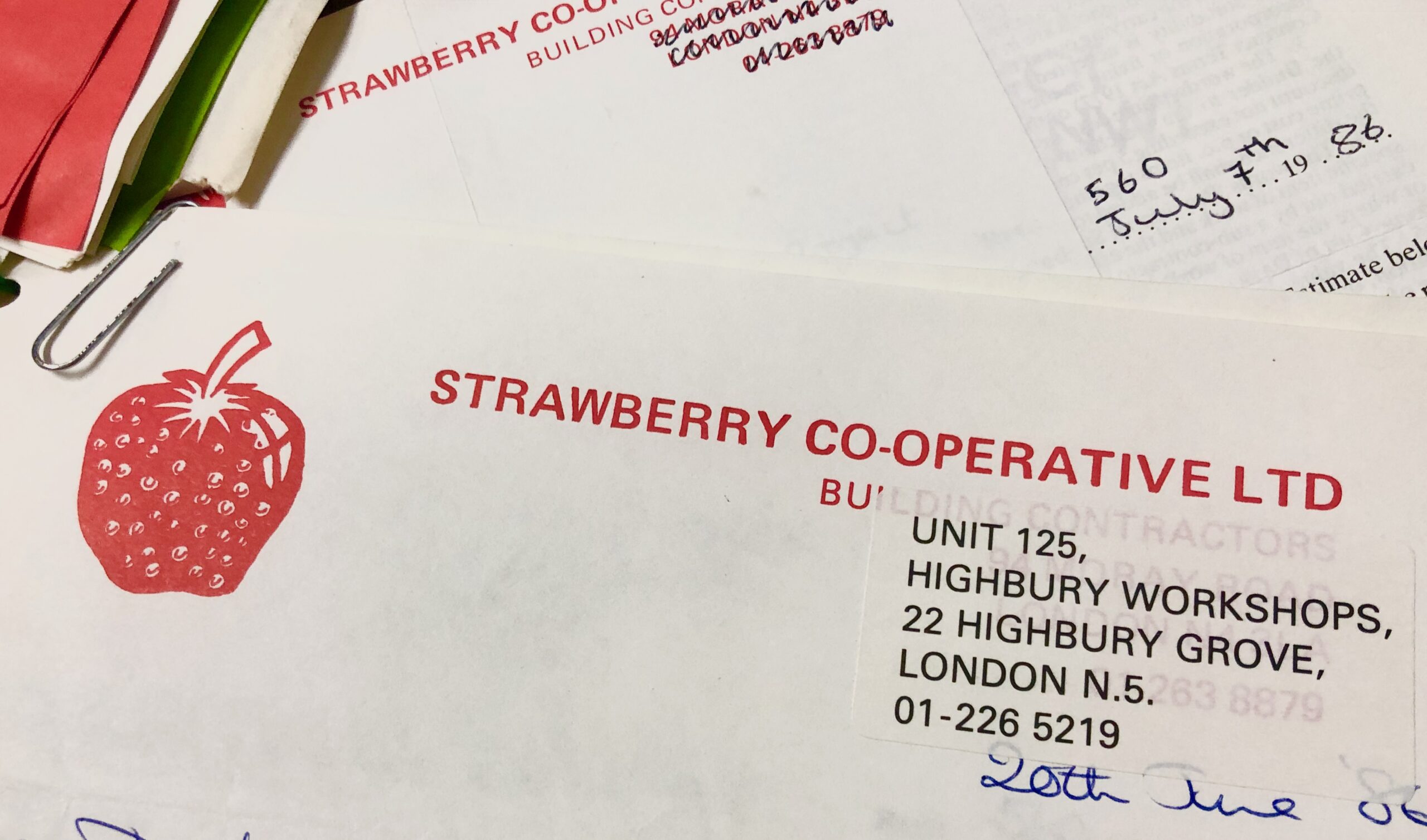

In the CLC&BLG Archive at GWL, the paper trail of letters, building plans and memos places Matrix within a wider ecology of explicitly feminist firms like the all-women Strawberry Builders Co-operative and the women-only woodworking collective Outskirts. Many women-only training initiatives were established around the same time as Matrix, all with shared aims of providing women with the technical skills and knowledge to enter into male-dominated manual trades – in Sheffield, for instance, Gwenda’s Garage was established to train women as mechanics, while the nationwide non-profit Women and Manual Trades helped women to find employment in skilled labour.

Founded in 1984, Women’s Design Service (WDS) was a co-operatively run Community Technical Aid Centre comprising women architects, designers and planners. Where Matrix provided voluntary organisations with surveys and feasibility studies, WDS provided initial consultation – in their own words, the group aimed to:

provide a useful service in offering a “prefeasibility” information [service] to groups to help them clarify their building needs.

Accordingly, WDS provided other women’s and community groups with technical help and advice on everything from getting value for money to sourcing building materials. They also produced several publications on designing for women’s needs and, later in their lifespan, they provided training to voluntary organisations on managing and maintaining their buildings.

Like so many fledgling women’s groups in this period, WDS was initially funded by the Labour-led Greater London Council, known for its financial and political support of minority groups before its abolition by the Thatcher administration in 1986. From this point onward the group’s funding was always precarious, and its survival through the tumultuous late 1980s can be attributed to the hard work of several individuals including Bramwell Osula, a former planner with the GLC, and Matrix’s own Jos Boys, who joined WDS as a development worker and pushed through research projects like the ‘Making Safer Places’ toolkit for developers to improve women’s safety on housing estates. This pivot away from direct engagement with clients and toward reshaping the urban research landscape ultimately proved very successful, and WDS thrived for over thirty years before winding up its operations in 2020.

The legacies of feminist design co-operatives

Like WDS, many feminist design and manual trades co-operatives have since dissolved or taken new forms, and the collectives that have emerged in their stead speak to both their achievements and their shortcomings. Recognising that the field of feminist design was overwhelmingly white and didn’t represent the experiences of Black women and women of colour, early WDS board member Elsie Owusu founded the Society of Black Architects in 1990 to integrate the contributions of Black and global majority professionals as both designers and clients. More recently, architects Selasi Setufe, Alisha Morenike Fisher, Neba Sere and Akua Danso established Black Females in Architecture, a network that aims to increase the visibility of Black women and women of Black mixed heritage in the industry – and since it started in 2018, its membership has grown to over 400. Last year, chartered architect Tumpa Fellows founded Female Architects of Minority Ethnic (FAME) to change the face of architecture by campaigning for equality for female architects of colour; FAME is currently researching the barriers faced by women of colour in architecture education.

More broadly, design collectives like Part W continue to challenge gender-based discrimination at industry, educational and policy level. Formed in 2018, Part W’s feminist agenda has its roots in the feminist design co-operatives that came before – their manifesto states:

We are impatient for equality. We call out gender discrimination in an industry that routinely excludes.

Now consider this, from Matrix’s introduction to Making Space:

We have all felt angered by male domination at work and in cities and we believe that our experience is a common one for women. We hope this book will help women to understand how the man-made environment fails to work for them and will start some ideas about how things could be different.

And start new ideas, they certainly did: the co-operative ethos and revolutionary (utopian, even) thinking of these early feminist collectives like it provided a blueprint for feminist design which carries through to the present. Where Matrix demonstrated how to disrupt the man-made environment, collectives like FAME and Part W take that disruptive spirit and make it their own, reshaping not only the built environment but the infrastructures that bear it out.

About the author: Lucy Brownson (she/her) is an archivist and PhD candidate at the University of Sheffield. In her doctoral research, Lucy explores the history of archival practices at Chatsworth House through a feminist lens. She’s also an organiser of Sheffield Feminist Archive, a community archive documenting grassroots feminism in the Steel City. Lucy is undertaking a placement in the GWL archives from July-October 2021; you can keep up to date with her work on Twitter.

References:

Eeva Berglund, ‘Building a Real Alternative: Women’s Design Service’, field 2.1(2008)

John Cunningham, ‘Thatcher abolishes the GLC’, Guardian online archive (1 April 1986)

Female Architects of Minority Ethnic

Fran Gallio, ‘“Jago Nari, Jago Banhishikha”: A Short History of the Jagonari Centre in Whitechapel’, East End Women’s Museum blog (2 Sept 2020)

Hackney History blog, ‘Dalston Children’s Centre 1982/3’ (9 Aug 2017)

Liz Kettle, ‘Go with Gwenda’s! How a garage in Sheffield drove a generation of women on to better things’ (2016)

Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative, Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment (1984)

Matrix Open Feminist Architecture Archive

Spatial Agency, ‘Women’s Design Service’

Christine Wall, ‘“We don’t have leaders! We’re doing it ourselves!”: Squatting, Feminism and Built Environment Activism in 1970s London’, field 7.1 (2017)