Introduction

This year marks Sir Walter Scott’s 250th birthday. He is a renowned literary figure who has a huge monument dedicated to him in Edinburgh’s city centre.

Jane Austen was a contemporary of his and her works are still revered, studied and adapted today.

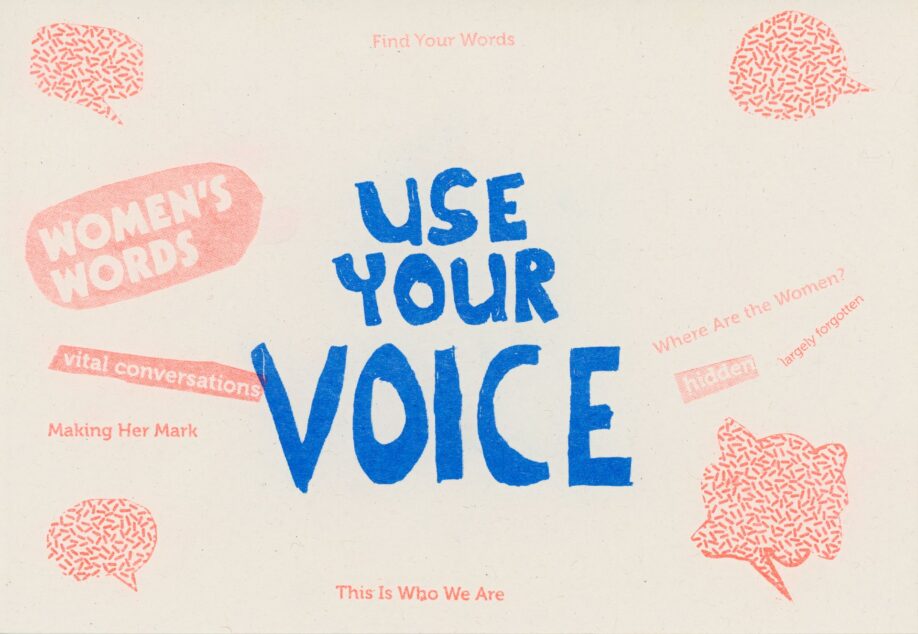

But what about Scottish women who were writing at the same time as these two celebrated authors? This blog post will explore the lives and works of four female Scottish writers whose literature was well known in their day (much more so than Jane Austen) but who are now largely forgotten.

Susan Ferrier (1782 – 1854)

Susan Ferrier was born in Edinburgh. Her father was a prominent lawyer and consequently she grew up as a part of Scottish high society. When her books were published there was much gossip and pondering over who her characters were based on in real life.

Following the death of her mother and the marriage of her older sisters, Susan kept house for her father. She began writing for fun with her close friend Charlotte Clavering (granddaughter to John Campbell, 5th Duke of Argyll – a client of her father’s) but soon decided to publish her work.

Susan once claimed she “could not bear the fuss of authorism” and chose to publish anonymously possibly because it was believed at this time that women should not be authors or have a role in public life but instead support the males in their families.

A possible another reason for choosing to publish anonymously is the aforementioned fact that some of her characters were based on real people.

However her identity eventually became known and her name linked with the books that she wrote. Sir Walter Scott considered her work very favourably even stating that her talent exceeded his own. Many believed, before the truth came out, that Sir Walter wrote Susan’s first book ‘Marriage’.

Some have called Susan the Scottish Jane Austen as ‘Marriage’ delves into similar themes as her English counterpart, such as the practices and beliefs of upper class society. Like Austen’s novels ‘Marriage’ is filled with lots of wit and keen observations.

A difference between the two’s works however is that the story of ‘Marriage’ starts with the lead protagonists marrying as opposed to finishing with a wedding. Susan herself never married, another parallel between her and Jane Austen.

Her two other novels – ‘The Inheritance’ and ‘Destiny’ – are regarded as pre-cursors to the works of Charles Dickens, with lots of long passages with rich detail, looming secrets, a complicated family history and eccentric and funny characters.

Elizabeth Hamilton (1756 – 1816)

Elizabeth Hamilton was born in Belfast to an Irish mother and a Scottish father. Her father passed away when she was a baby and she was sent to live with her aunt and uncle who owned a farm near Stirling.

Elizabeth finished school in her early teens but continued to be an avid reader after leaving formal education. She read all the great thinkers of the day and was very interested in educational and moral philosophy.

Her most famous book ‘The Cottagers of Glenburnie’ tells the story of Mrs. Mason who comes to live with relatives in a small village in the Highlands after having lived away from Scotland for a while. She is shocked to find the village in a run down and dirty state, with all the villagers taking the attitude of not being ‘fashed’ or not being bothered to make their surroundings cleaner because they feel there is no point; nothing would change.

Mrs. Mason takes on the task of cleaning up the village and making things tidy and organised.

‘The Cottagers of Glenburnie’ became very successful not just amongst the Edinburgh elite but also amongst people living in small Highland villages in Scotland that looked like the fictional setting of the novel. This book spurred on some of these villages to clean up and improve their surroundings showing how it was very influential.

Mary Brunton (1778 – 1818)

Mary Brunton was born on one of the Orkney Islands to a distinguished military family.

Unlike the other women in this blog post Mary was happily married. When she was twenty she eloped because her mother did not approve of her chosen partner – a Church of Scotland minister Alexander Brunton. Alexander went on to have a successful career as a minister but also as a professor at the University of Edinburgh.

Mary did much philanthropic work and cared about the welfare of her parishioners. She also was greatly interested in philosophy and history, an interest her husband supported. Mary also believed that women should be taught ancient languages and mathematics, something few women were able to accomplish in this period.

Mary had written things such as recipes and letters before beginning to write literature for fun. She did write many poems as a young teenager but looked back at these with dislike. Although she began writing novels for fun she was encouraged by a friend to publish her work.

Her first novel was called ‘Self Control’ and was published anonymously in 1811. It tells the story of Laura, a protagonist who has never left her remote Scottish village until she is forced out of it and commences on a journey that will take her to Edinburgh, London and eventually Canada. She learns how to survive on her own when she can never fully depend on anyone to look after her.

‘Self Control’ was an immediate success and went through four editions in its very first year of publication. Mary’s next novel was entitled ‘Discipline’ and like ‘Self Control’ it is a sternly moral tale. It is believed that Jane Austen based her character Emma Woodhouse on the protagonist of Ellen in ‘Discipline’. Unlike Jane Austen’s novels however, when Mary’s characters are low on funds they think about ways they can make money. They get jobs and earn for themselves.

Mary’s novels “redefine[d] femininity in the period by portraying female characters who were strong in the face of adversity and often alone.”

Catherine Sinclair (1800 – 1864)

Catherine Sinclair was born in Edinburgh and was one of thirteen children. Her father was a prominent politician who had a key role in many aspects of public life at the time.

Catherine was educated at home and worked as her father’s secretary from the age of fourteen. This job involved writing from dictation which was a good grounding in the craft of writing.

Catherine wrote many different kinds of books during her lifetime, including a children’s book she originally wrote to entertain her nieces and nephews, as well as novels and also travel books.

The children’s book that she wrote – ‘Holiday House’ – is her best known work and was one of the first books to give a realistic picture of children who are naturally mischievous and argumentative.

Catherine is unlike Susan Ferrier and Mary Brunton as she chose not to publish anonymously. She stated the reason for this was that her father disapproved heavily of anonymous publication. Placing her name on the books she wrote was a brave move, one that Sir Walter Scott did not make. Although he put his name to his poetic works, he published all of his novels anonymously.

During her lifetime Catherine also did much charitable and educational work. She founded a mission school and set up many public benches and fountains. As well as this she established a Sinclair Cooking Depot which provided good, cheap food for those living in poverty. As a result of all this a monument was dedicated to her which can be found in Edinburgh:

Notice however the similarities and differences between the monuments dedicated to Sir Walter Scott and that of Catherine Sinclair. Although similar in style, one sits alone on one of Edinburgh’s busiest streets, a focal point of the landscape. The other is much smaller and hidden away by trees. An interesting symbol of how often women are overlooked in history as well as being overshadowed by men.

Conclusion

So why have these four women and their works been largely forgotten? There are several possibilities, one such reason is that they were each very religious and this is reflected heavily in their books with long passages debating morals that some people today often find a challenge to read.

Furthermore, in the case of Elizabeth Hamilton, they are very negative towards Scotland. Elizabeth’s views of the villagers in Glenburnie not being ‘fashed’ to improve their surroundings can be viewed as quite patronising, ignoring the fact that the feudal system in place in Scotland at the time highly disfavoured the lower classes of society, leaving them in an impoverished state that was out of their control.

It has also been argued that because Sir Walter Scott and Jane Austen are linked with this time period, we already have someone representing a Scottish perspective and someone providing a female perspective.

But why should there only be one of each? Why not celebrate the other writers who were both Scottish and female?

Each of these four women have something of value to offer and despite their lack of popularity today should still be regarded as well worth a read. They each provide a social commentary of the times in which they lived.

If you would like to find out more about these writers and other contemporaries of Sir Walter Scott you might be interested in the upcoming Story Cafe; Women of Letters on Thursday 27th May 2021. For more information and to book a ticket for this online event please click here.

References

- ‘Where are the Women? A Guide to an Imagined Scotland’ by Sara Sheridan (available to browse at GWL)

- https://www.nls.uk/learning-zone/literature-and-language/themes-in-focus/women-novelists/

- https://www.saltiresociety.org.uk/awards/outstanding-women/outstanding-women-of-scotland-community/2015-celebration/susan-ferrier/

- http://secretedinburghguide.blogspot.com/2014/12/catherine-sinclair-monument.html?m=1