We’re delighted to share another blog post by Shirley Henderson. Earlier in the year Shirley had a clear out resulting in reflections on knitting and feminism. Here, she voices the memories of elocution lessons sparked by her most recent discoveries, which she has kindly gifted to GWL.

On the up

Brought up in a Glasgow suburb by a father from Parkhead and a mother from Milngavie via Dennistoun, the class tensions strained through the curtains of our brand-new 50s semi. We were on the up.

My mother was big on ‘speaking properly’: “It’s Helensburra not Ellnsbru’, Eddie; it’s restowrong not restewrant.” So, while dad took my brothers off to the football or to Bill’s Tool Store near the Barras, I got sent to Miss Gilbert’s for the weekly speech and drama class, or as Miss Gilbert put it, “elocution”.

We were girls and boys. I think, maybe, we were a collection of stutterers, lispers, hare lips and accents. I was marked down as having a “weak S”. But the classes were generally popular in a small town with few diversions for children. If you were keen, you could graduate from Miss Gilbert’s and go to the Athaneum on Saturday mornings (now the Conservatoire) for youth theatre.

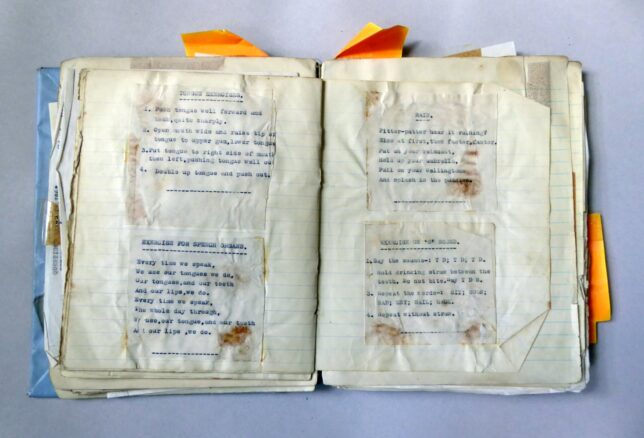

What was this “elocution”? It involved learning theory about diction and articulation; about poetry scansion; and also breathing and speaking techniques. We had to stand with one foot in front of the other, toes pointing out; up tall; and recite. It could be short poems, excerpts from Shakespeare, bible readings.

Sometimes, we young ones were put together with the many adults who went to Miss Gilbert, forming a great speaking choir. We’d give performances in Glasgow at the Canal Boatman’s (or Bargeman’s) Institute, designed by John Honeyman & Keppie with the clock design (unused in the end) by Charles Rennie MacIntosh, and pulled down in 1969 to make way for the M8 which sliced Glasgow into pieces. Cowan’s, the joiners and wrights that my great grandpa from Dennistoun worked for, are among the construction tenders.

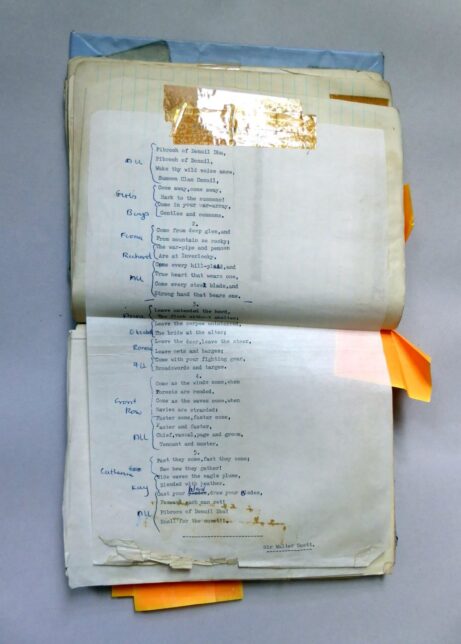

Those speaking choirs are a mystery when I think back. Who were all those adults? Does anyone else remember them? As a child I was quite overwhelmed hearing the room echoing to the sounds of ‘Scots Wha Hae’: the musicality coming from the different timbres and shades of voice. And how ironic, ‘Scots Wha Hae’, given that some of us were sent to elocution so we would learn to speak properly (or at least not too Glasgwegian: a bit was fine, but what bit?) and to ditch the Gaelic vowel sounds from ‘filum’ and replace the ‘u’ of ‘mulk’ with an ‘aye’.

A friend tells me that when she was at primary school in Edinburgh her entire class had to do elocution at school and “had to recite The King’s Breakfast by AA Milne ad nauseam and stop saying guuuurrrrrllllzzzz”.

She adds, “It’s not a pronunciation thing but non-Scots remark on my use of ‘How’ when they think I should be using ‘Why?’ I moved to England when I was 16 and got terribly bullied for my pronunciation so I changed it quite a lot, I think. My brother too – he took to shoplifting when he was 11 to prove that just because he couldn’t speak right didn’t mean he wasn’t one of the lads…”

Miss Gilbert, and her two sisters, a trio of Misses Gilbert, were Victorians. The house was dark; the chairs were hard-backed and carved mahogany or ebony; the tablecloth was chenille. Their father had been a canal boatman from the institute, and a ship’s wheel formed the gate to the house. We stepped through that into another time, to perform rites more familiar to those of the 1860s than the 1960s.

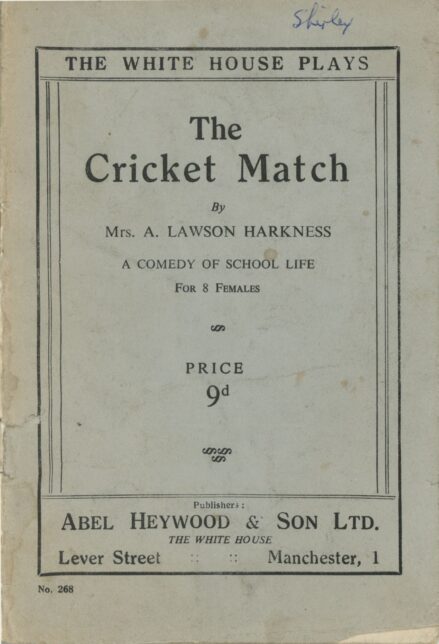

The Cricket Match

Sometimes, we performed little plays. I still have a copy of one: The Cricket Match: a comedy of school life for 8 females by Mrs A. Lawson Harkness.

There’s no date but the “hints for producers” for 32-minutes of “spirit and zeal” not to mention sexism, racism, snobbery and classism indicate some Edwardian fancy:

“Where possible have a piano on stage, as instructed; it will improve the “go”. But where piano is not available, let the singing be well rehearsed, and performed with girlish abandon. There is no need to refer to music or tunes, the rhymes and songs are too well known. Even with the piano, smart vamping will serve.”

The Cricket Match is a ‘White House Play’ published by Abel Heywood and Son Ltd of Manchester, and one of a series of dramas, operettas, recitations, monologues, duologues and community dramas. The irony continues in that we were being taught about how to speak in a certain way and learn certain values using materials from a publisher founded by English publisher, radical and mayor of Manchester, Abel Heywood (1810-1893) who was also a Chartist. His main aim in setting up a publishing house was to bring education to those who couldn’t afford to go to school, and who were likely out working by the age of 12. Here we were, prancing around in the Glasgow suburbs, learning what I hope would have been anathema to him.

But there are many ironies and contradictions in this story. I think there is a book in here! In some of its manifestations, elocution seems to have been a form of accomplishment, which by the 1950s, and according to this YouTube clip was about perfecting diction and timbre in the context of acting and theatre, before it pretty much died out or translated into ‘speech and drama’, which is where I stepped in as a girl.

Speaking out and speaking up

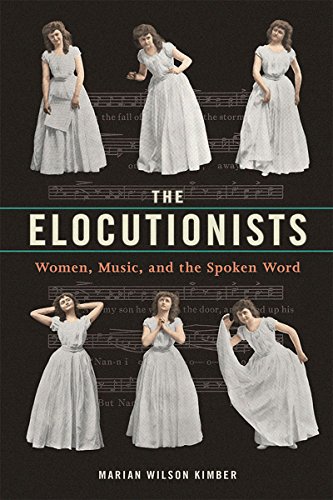

But according to an American account of the phenomenon, elocution emerged in 1850s America as a new type of performance which combined recitation of poetry or drama with musical accompaniment. In her book, The Elocutionists: women, music and the spoken word, Marian Wilson Kimber, associate professor of music at the University of Iowa, describes how the intersection of music and speech, as a genre, was dominated by women. It gave women a public space for a type of performance, seen as high art, and considered suitable for women (unlike acting and theatre, which were seen as morally suspect for women). Through elocution women could speak out and speak up.

And those who taught the form, ‘the elocutionists’, were overwhelmingly women because this was a suitable job for women (unlike acting) – although, according to Professor Kimber, there was a backlash against elocution’s professionalisation of women after WW1 (and I assume those women got sent back home after the war too, along with the munitions workers). Her book is a fascinating insight into performance, gender and history; the extent to which women ‘are allowed to’ contribute to and shape art; where they might do this; and the subjects considered appropriate.

Professor Kimber wrote in an email to me that she’d done some research into some British spoken-word performers from the beginning of the twentieth century who were men. She said that she’d collected a few British elocution books: usually decorated with men in tuxes, unlike the American ones which feature women.

She commented that elocution flourished in Australia and other British colonies and that the height of elocution in America was also a period of immigration with elocution teachers of the time likely helping immigrants assimilate. One of her colleagues was sent for speech training so that she would sound less like she was from Brooklyn.

Professor Kimber’s book discusses women performing humorous pieces. Yes, it appears that women could also be funny in the 1850s. She’s been performing samples with pianist, Natalie Landowski. She says that it started out as an experiment to see if they would still entertain an audience, and is happy to report that they do. There are four videos on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLUBuQZ0S3IhMaoTfpFxvxjijglZLyyInO

Looking at my copy of The Cricket Match and remembering my experiences at Miss Gilbert’s, it wasn’t all that it seemed. We were taking part in something that was old-fashioned even then, and dying out even as some of the best-fashioned parts of Glasgow were being demolished. But we were also participating in a movement which, perhaps, started as a way for women to have a strong voice, and to earn a ‘respectable’ living. Certainly, for the Misses Gilbert, by then in their 70s, the income from those lessons kept them housed and clothed and fed when, as was the rumour, they might otherwise have expected to have been married to, and supported by, three young men who were killed in the WW1 trenches.

Shirley Henderson (March 2021)