In the summer of 2020 I wrote some blog posts for GWL based on my undergraduate dissertation on the #MeToo movement (you can read my first blog post here). Fast forward to 2021 and I am almost half way through my Masters degree in Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods at the university of Strathclyde. It hasn’t been an easy year for many of us and studying a Masters has certainly been challenging. But through my Masters I have learned so much and met many amazing women! Here, I got to meet (through zoom) Professor Karen Boyle.

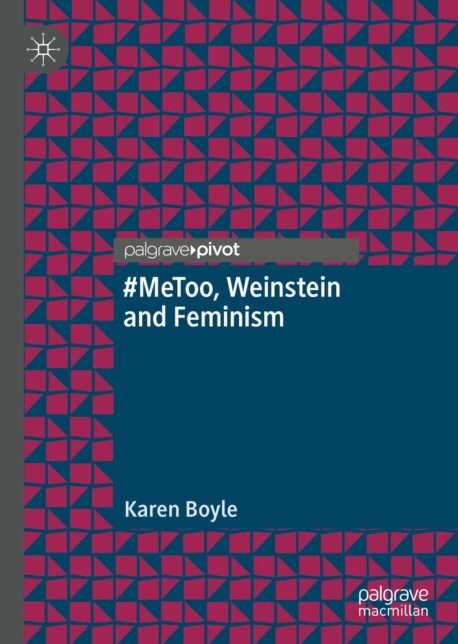

Karen teaches Applied Gender Studies at the university of Strathclyde and is the author of the book, “#MeToo, Weinstein and Feminism”. This is available in the Glasgow Women’s Library. As I had previously looked into the #MeToo movement I was interested in learning more from Karen.

So, today’s blog post is an exciting conversation I had about the #MeToo movement with Karen. Grab a cup of tea and a blanket and read on!

Jennifer

Could you, firstly, explain what the #MeToo movement is, and if referring to it as a “movement” is problematic or not?

Karen

In the work I’ve done I do refer to “Me Too” as a movement, but I distinguish between “Me Too” as a movement and “Me Too” as a hashtag. And I’ll just explain why I think that distinction is important. “Me Too” as a hashtag started trending globally in October 2017, after the actress Alyssa Milano asked her followers to tweet #MeToo if they had experienced sexual harassment, specifically focusing on women. At that time, the first stories about Harvey Weinstein hit the press. So, there was a bit of a reckoning about what was going on, particularly in the entertainment industry. But as we know, the hashtag took off globally to many other sectors, not just the entertainment industry, and led to literally millions of women and men worldwide sharing experiences of sexual harassment and assault under #MeToo. So, it created this huge amount of public discourse around sexual harassment and prompted things to happen in relation to the careers of some successful men, for instance. But more fundamentally, I think, it brokered this wide discussion about sexual harassment: What is sexual harassment? What is assault? What’s normal behaviour and how do we challenge it? So, it’s a really important hashtag. And it has elements of a social movement in it.

The reason I resist equating #MeToo with a movement is, first of all, a lot of people were tweeting #MeToo which was the beginning and end of their involvement. That’s not a criticism, that’s just a noticing. Secondly, people using that hashtag didn’t necessarily have much else in common beyond the fact that they were sharing these stories, they didn’t necessarily think it required the same action, they didn’t necessarily come at it from the same political stance, or indeed from an understanding that violence is gendered.

In contrast, the Me Too movement was founded by African American, Tarana Burke in 2006 and was a specific response to the needs of young women of colour in the US. The way that they were being marginalized within existing services for survivors or the fact that there weren’t any specific services for them. So, Burke’s “Me Too” talks about speaking out and the importance of speaking out, just like the hashtag. But in a sense, Burke is positioned within a much longer tradition of activism that’s taken “speaking out” and turning it into survivor advocacy, to support services and to campaign for change. So, although the things are absolutely linked and speaking out can absolutely be part of a movement, speaking out is not the end point of a feminist movement for social change, particularly in relation to sexual violence. Burke’s “Me Too” and that tradition of speaking out has a much longer history, not just going back to 2006, but a much longer history of speaking out about injustice. So, speaking out is politically important, but it’s not the end point.

.

.

Jennifer

And so, you’ve written a book called “#MeToo, Weinstein and feminism”. Could you tell me a bit about the book and what motivated you to write a book on the #MeToo movement?

Karen

There were a few things that bothered me about the wider “Me Too” discourse. One was the historical amnesia in much of the coverage. So, that’s what I just referred to in terms of Tarana Burke. And that was amended to an extent. She has had a mainstream media profile. But she herself has reflected on the limited conditions in which her media profile has been built. That is, acknowledging her as a founder of the movement but as though she just founded it and then sat twiddling her thumbs until Alyssa Milano tweeted. That was one of the things that bothered me. This main stream story about #MeToo was so obviously linked to activism that had been going on for decades. And yet, it was absent in the story that was being told. I remember looking at the press or on television in the aftermath of the Weinstein revelations and being absolutely gobsmacked. Gobsmacked that this coverage wasn’t including experts from Rape Crisis who have been doing this work for forty years, who could put this understanding into a broader context. The media could have told us more about how the law has worked to protect perpetrators in different legal contexts, for instance.

So partly, it was a reaction to that historical amnesia of the mainstream coverage. And partly, it was a frustration with the mainstream coverage becoming totally self-referential. And, for instance, it was criticizing #MeToo for not being intersectional. That, of course, is a really important critique. The voices of white celebrity privileged women were the voices that were being heard most clearly. But it was the media that was amplifying these voices. The feminists on the ground who have been doing this work for decades, they aren’t the ones who are necessarily amplifying celebrity voices. So, I was frustrated that the story about #MeToo in the media was missing that longer intersectional history. It’s an uneven intersectional history, I’m not saying for a second that the feminist anti-violence movement has always got that right. But I wanted to understand those historical links. Because unless we see those historical links, there’s a danger we just keep repeating things.

I guess because my background is in film and television studies, I was interested in how these stories about the industry were, on the one hand, about workplace sexual harassment, but were also about how we understand the cultural norms of the film industry and how we talk about film, how we talk about value, how we talk about greatness.

Jennifer

I just wanted to pick up on a point you mentioned about important feminist organisations being missing from the media coverage in the movement. Why was this happening?

Karen

A few different things were going on there. The work I did specifically looked at press. I found that articles about Weinstein and feminism tended to cast doubt and suspicion on feminism. So, we’re talking about prominent celebrity feminists and whether or not they knew about Weinstein. It became a really individual story about feminism’s failures, rather than looking at decades of activism and debate. Also, part of the problem was that #MeToo, although it was very much a collective story from the start, hinged on celebrity individuals.

From speaking to friends and colleagues in feminist anti-violence movements or the feminist sector more broadly in Scotland, I was struck by how they were being approached for comment on #MeToo. The same was true for me as an academic in this field. We were being approached for comment when it could be pitted as a feminist cat fight. For instance, when a celebrity feminist said something that cast doubt upon the #MeToo movement, the media wanted to know what feminists had to say about that. But the mainstream media wasn’t approaching those feminist organizations otherwise. And it was a curious time because feminism was everywhere, there’s no way to talk about #MeToo without talking about feminism. And yet, it was an individualized story. So, many of these fantastic organizations who’ve been doing really important work for decades got written out. It was like we’ve just discovered that Hollywood has sexual harassment problem. Like, really?

Jennifer

Do you think the way the media has focused on the individual story, as opposed to the wider structural issues, has kept the personal as the personal rather than transforming the personal into political movements and political change?

Karen

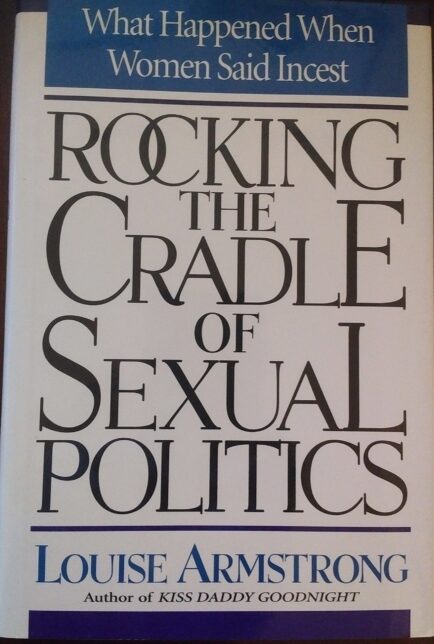

That’s a great point. I’ve used a lot of work by Louise Armstrong. She is a US feminist, who was one of the first people to speak publicly about experiences of incest and child sexual abuse in the 1970s. She wrote a fascinating book in the 90s called, “Rocking the Cradle of Sexual Politics: What Happened When Women Said Incest”. This was a reflection on what happened to her and the way her thinking had been publicly portrayed. So, speaking out and using the media to speak out was really important. But she discusses how this was part of a feminist process about, as you said, making the personal political. But when the media got hold of the story, they wanted to retain the personal within a much narrower box. Armstrong says that, for the media, the personal is the personal. And so, they become stories of individual trauma and not stories that we need to understand in order to arise from structural intersectional inequalities. And there’s another element to that, which she argued. So, there was a personal as the personal but also, at some point, just making the personal public became the end goal itself. Being critical of that is really important. So, her work is a really great read on this stuff.

Jennifer

For me personally the #MeToo movement seemed to be this huge turning point as people started to listen on a more global scale. So, I noticed that it seemed to spark conversations within my own social circles or raise awareness at least. But, do you think it hasn’t done enough?

Karen

That’s a really important point and I would never want to minimize the importance of “Me Too” as a hashtag because it has opened up a global conversation. Armstrong says, in the book I just mentioned, she talks about people speaking to her about the incest survivor’s movement, and at least they started a conversation. And she’s got this brilliant line where she says,

but our aim wasn’t to start a conversation, our aim was to raise hell and change things.

Louise Armstrong

And I think that’s the bit we’re still waiting to see fully realized. So, #MeToo has started a really important conversation. It’s energized and politicized lots of survivors and people who now have an understanding of sexual harassment in a much broader way and sexual assault more broadly.

But when we will really know things have changed in the short term is when Rape Crisis centers are securely funded, when sexual harassment in the workplace has clear consequences and when there’s not a culture where sexual harassment is still the subject of jokes, for instance. Now, a lot of that has shifted in the last two years but it’s not shifted conclusively. So yes, there’s progress. But one of the things that always worries me about big media stories is a tendency to go, oh shiny and new and everything’s changed. And then we’re back to square one again in another five years. So, it’s how do we maintain that momentum? How do we keep that understanding at the forefront of what we do? We can’t have rose tinted glasses about #MeToo. For instance, immediately when #MeToo started, there was an online backlash. A backlash that involved people being threatened and trolled. So, we’re not out of the woods yet.

Jennifer

Absolutely, and, for me, the backlash felt really quite intense. Could you explain a bit more about the backlash?

Karen

There’s a great critic called Sarah Banet-Weiser who’s written a book called, “Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny”. She argues that the popularity of feminism comes at a cost of an equally popular resurgence in misogyny. For instance, the fact that Trump was elected despite those tapes where he was clearly glorifying sexual harassment, despite the allegations of sexual assault against him. At the same time, there were the women’s marches and resurgence of popular protests against Trump. I think those things often go hand in hand.

In my own career, I started off teaching women’s studies and, through the 1990s in the UK, there was a decline in women’s studies as a subject. I’ve always thought that was about complacency. With the election of the New Labour government, with more women in Parliament, with fairly secure funding for certain services, we’ve done it all. Now, no feminists I knew in the 90s were saying that. They still saw the work that needed to be done. But the popular discourse was, we’ve done it now, we’re fine, we’re sorted. At the moment we’ve got a resurgence of misogyny and that leads to a resurgence in popular feminism. But the feminist work on the ground has never gone away. Rape crisis in Scotland, for instance, has been operational for more than 40 years. It didn’t stop in those periods where the media wasn’t talking about these issues. And I think that’s really important to understand. So, in some ways the visibility of these issues, I’m never going to say it’s a bad thing, but it’s a double-edged sword for sure.

Jennifer

I noticed something in my own research into the #MeToo movement that I did for my undergrad, that participants thought that change would come from altering our discourses and puling people up for sexist language. And I was wondering if you thought that our discourses do hold a lot of power in terms of normalizing the sexualization of women?

Karen

I think that’s really encouraging to hear because change has to take place at every level. And there’s a quote by Helen Benedict, who wrote a book about sex crime in the news in the 1990s called, “Virgin or Vamp” that I’ve quoted practically in everything I’ve written, which is that,

changes in representation don’t only follow on from changes in reality, we can also lead the way.

Helen Benedict

And the example you just gave points to that. Changing how we talk about things is not inconsequential. Because the way we talk about things leads to the way we imagine what’s possible. Of course, it’s not enough in itself. But I think that’s really encouraging to hear that the participants in your study saw the way they talk about things, what they listen to and what they stand for as things that we need to think critically about every day, not just in university courses or in workplace sexual harassment training but also in the pub, assuming we ever get to go to the pub again, in the zoom chat might be the best way to put it.

Jennifer

It definitely felt like an important point in my study. But it seems, to me, that any kind of criticism of language seems to provoke another backlash.

Karen

I think it’s often seen as; oh, you’re just being PC.

Jennifer

Exactly, you’re kind of seen as a “snowflake”.

Karen

Even that term is so hugely insulting and problematic. And also, really aimed at young people which I think is trying to put young people off activism.

Jennifer

Yeah absolutely. And so, for the final question, I’d like to bring it full circle back to your book. What do you hope people will gain from reading your book?

Karen

Not one thing really, except maybe being alert to the longer history of the stories we encounter in the present. But equally, I wouldn’t want to present my book, which isn’t a history book, as a definitive history and account of a movement because movements are dynamic and they change. It’s more thinking about what we can learn from what’s happening now, what’s gone on before, from places or people we’ve not engaged with historically and think about how to move things forward. So, what I’m trying to say is that, I hope the book is part of an ongoing discussion. I’m as happy for people to disagree with me and tell me why as much as I am for people to use it as a tool for their own activism.

.

Resources:

The following books by Karen Boyle are available in the Glasgow Women’s Library:

#MeToo, Weinstein and Feminism

Everyday Pornography

Media and Violence: Gendering the Debate

Carla 2020 Keynote: Thinking and Writing About the Media Industry Post MeToo

You can watch this fantastic discussion on the #MeToo movement with Karen at the Carla 2020 conference by clicking this link.