“Every act of communication is a miracle of translation.”

― Ken Liu, The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories

“Every act of communication is a miracle of translation.”

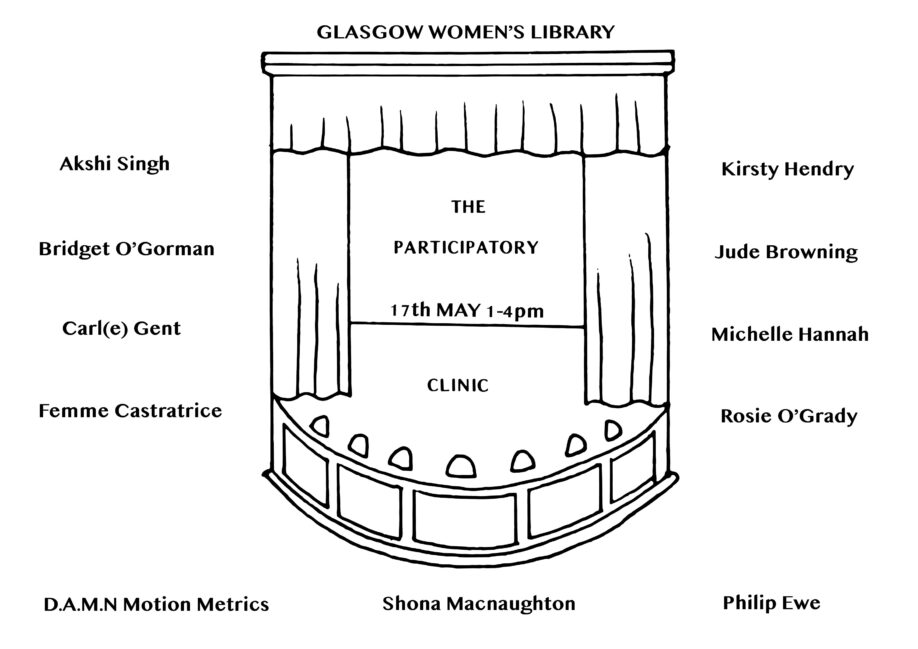

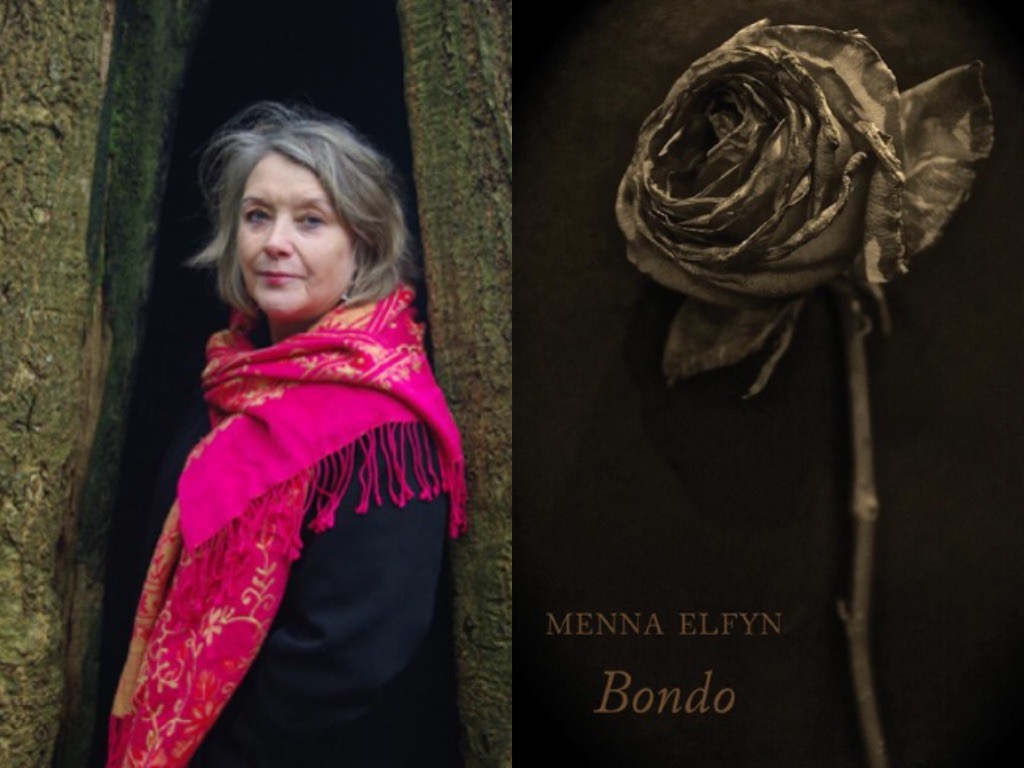

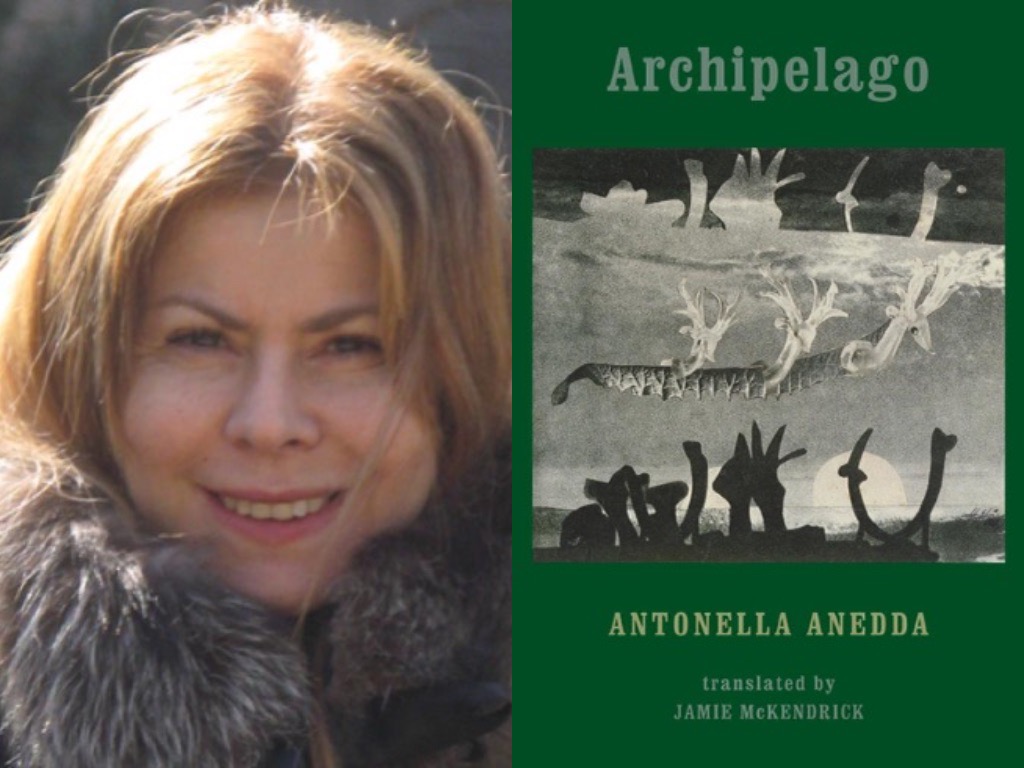

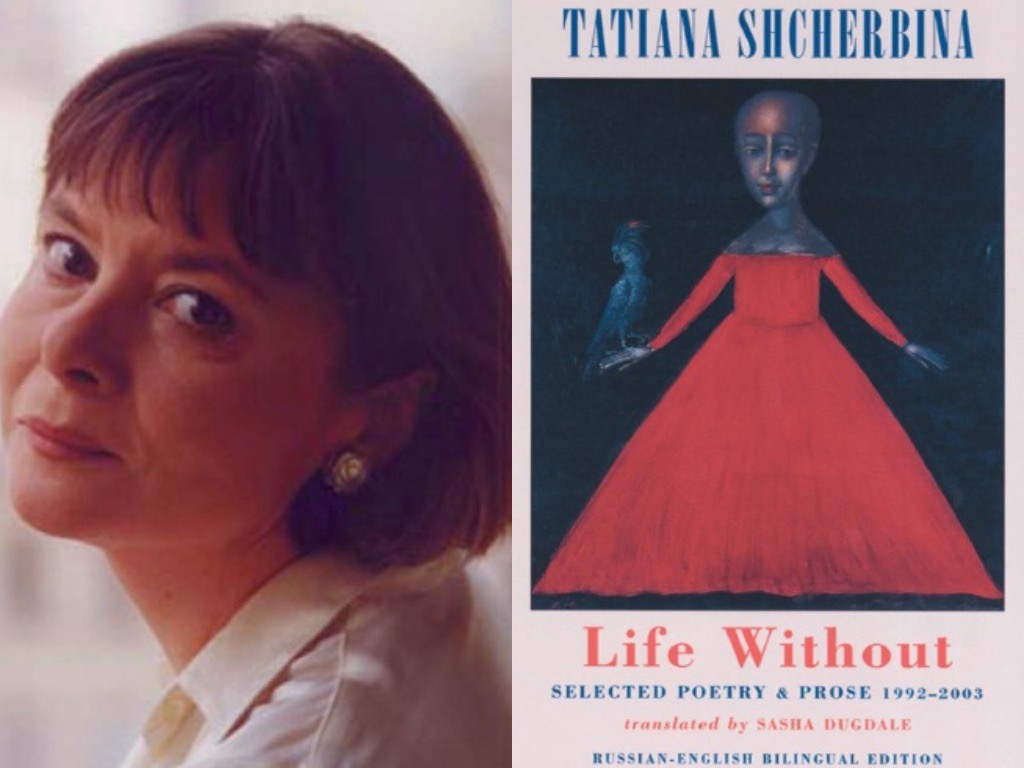

― Ken Liu, The Paper Menagerie and Other StoriesBloodaxe’s billingual poetry collections like Menna Elfyn’s Bondo, Antonella Anedda’s Archipelago and Tatiana Shcherbina’s Life Without are works of wonder. Glasgow Women’s Library is dedicated to raising the profile of such works as much as possible due to the unity and connection such writing creates between us all.

The poems are communication of the most intimate sort, translated and interpreted across language. Defined by feeling and somehow spoke in different words getting at the same essential things, thoughts and feelings. Like filmmaking, a bilingual book involving translation requires collaboration. For Elfyn’s Welsh-English work the translators creating and recreating with her include, Elin Ap Hywel, Gillian Clarke, Damian Walford Davies, Menna Elfyn herself and Robert Minhinnick. In the Italian-English Archipelago by Antonella Anedda, the translation is done by Jamie McKendrick. A duo communicating across the Romantic, Germanic and beyond. Finally there is Tatiana Shcherbina’s Sasha Dugdale who helps brings Russian Rhymes and poetic devices into English.

As Elfyn says, her translators enable her to “write poetry solely in the Welsh language while nesting under its bondo-eaves”, the title of the collection. With them her “need for a roof over my language as well as to be able to roam far and wide in English” is possible. Elfyn considers everything from welsh identity to religion and history to nature, sometimes in the same poem. Her Misting/Niwlo considers mist as both a natural phenomenon, and a barrier Welsh people have encountered in trying to understand welsh identity today, and far into the past. The “mysteries” of who they “never were” and will “never be” haunts her poem’s narrator who yearns for some acre of Welsh creation. Benediction of Eaves is a beautiful exercise of the human tongue that dances rhythmically as its read or spoke. The translator has likely captured some aspect of the welsh version Bondo. My favourite however is Singing Song for Starlings/Ysgol Gan y Drudwns. The quote it opens with is by Gwalchmai Ap Meilyr who wondered at how, “a bird’s instinct is to know morning”. The poem follows young starlings in the “here and now” who listen to ‘the whitecoats explain” how “birds remember their old songs”. It’s a beautiful poetic exploration of the many mysteries that surround the world of the feather creatures that fly above our human lives.

Antonella Anedda’s collection, and her poetic voice, are described in the collection’s introduction by McKendrick as having “ a mind for winter” instead of sticking rigidly to Italian lyrical traditions. She was brought up hearing not just Italian ,but Logudorese, Catalan , Corsican French and La Maddalena’s dialect. The sounds in her memories were “harsh ones”, “thick with consonants and shorn of adjectives” which made her understand her “own Italian in the light of those sounds”. She descends into “Una Lingua non bassa, ma profonda”, a language that isn’t base or vernacular ,but profoundly deep. Her Sandarian identity is as important to her as her Italian. McKendirck adds that often translating her can be an interesting experience with the prose poem, non riesco a sentirti, sta passando un camion/ I can’t hear you-a lorry laden with iron, being challenging and requiring transfiguration into verse to get across the same feeling and meaning in English as in Italian. Poem I is a work that deeply touches me in English and what small bit of Italian I have through university. Talking of hospital wards and amplifying the pain and passion found in every clinical room. The concluding line is a work of brilliance: “I vivi si chiamano come da barche lontane/The living call to each other as from distant boats”. A beautiful melancholy poem is A mia figlia(19-11-1993)/ To my daughter(19-11-1993), a poem from Antonella to her daughter. Written in the year I was born I found it especially touching and showed it to my own mother. Anedda talks of the now and the next, of when we are here and “when neither you nor I will be here”. Other mothers and other daughters will one day “watch one another as today”, but right now it us. In works like her Rembrant, giovane che si bagna in un ruscello(1655)/Rembrant, young woman bathing in a stream(1655). Mckendrick effortlessly translates her words regarding Henderickje Stoffels, capturing the clear penetrating imagery so beautiful yet direct that Anedda creates.

Of final consideration is Shcherbina’s Life Without, a selection of her poems and prose from 1992-2003. As Sasha Dudgale notes, the writing was composed in a post-fallen Berlin wall Russia where the USSR was gone. Russia seemed to be moving towards a free-market and democracy. Rapid change and upheaval was present. As a Muscovite who lives in and lives through Moscow she wrote as her world changed forever. She searches for her family origins ,but isn’t afraid to talk of Russia kindly or critically. She swears and meets the flowery with the fierce in her word choices such as in To Apollo where she says “God’s answer phone is crap” or in ***(1995) where she describes trying to “get pissed” when something is eating at her. She’s tried changing her country, wardrobe and hairstyle ,but can’t. Comercialism in the new Russia means as ***(1996) states, that “Apart from love everything can be bought”and that as Viral Infection:Lovelessness ends, you can “loan” a “phrase from the bank”. As Dudgale points out, she uses the new Russian slang word for money: cash throughout her writing. A new word for new money. Shcherbina portrays the brutal reality of the past and present Russia through making the Berlin wall alive in ***(1994). The monsterous wall, she says, “ collapsed and shook us all about. It consumed and killed and spied upon.” And only now “in its shadow” can Tatiana walk out and be free. Ru. Net is the most direct exploration of the changing country which she notes “has ceased to exist” in the way it was. The internet looms over Russia. In the end Tatiana emphasises, in ***(1998), that “you are a Russian, like as not”.

Her prose is equally engaging, informative and beautiful. Her Recent History of Moscow follows the city through her decades on earth. The singing of exhortative songs on loud-speakers is lost to history’s mist, she records, and she notes the decade seemed one of constant singing before considering this Russian musical sphere in connection to the newly invented tape-recorder. Where once songs empowered the state, this device enabled new singers to “undermine the enormous graven image of the state, the machine which used people as its cogs”. Through this simple device she was politically awakened and recognised the dark side of the propaganda littering her childhood. Tatiana describes the 90s as encapsulating a “Wild West Capitalism” in Moscow. A city so different from just 30 years previous.

Her wonderful The Family Unit follows how one deals with the legacy of those who came before and the relatives we are bound to in life. As someone with a complex family history that goes to places like Turkey, Bulgaria, the Scottish Isles and Ireland, the line “The Family’s roots broke upon me” is a stunning striking piece of writing. Both Shcherbina’s poems and prose, in the original and in English through Dugdale, are incredible literature that you must read.

To sum up, the bilingual poetry collections that publisher’s Bloodaxe have released in various languages, are fantastic pieces of literature that warrant a read, whether you can enjoy it in two languages, or marvel at the flawlessness of them in translation.