I am not an angel,’ I asserted; ‘and I will not be one till I die: I will be myself….You must neither expect nor exact anything celestial of me – for you will not get it, any more than I shall get it of you: which I do not at all anticipate.”

― Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre“Well-behaved women seldom make history.”

― Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make HistoryWomen must come off the pedestal, men put us up there to get us out the way.

-Viscountess Rhondda

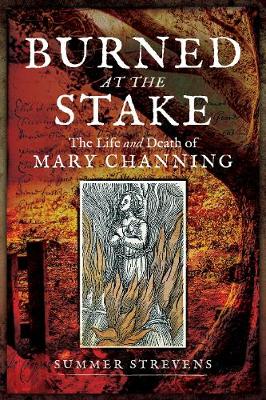

The stories of Mary Channing and Mary Bateman are ones that have been silenced for hundreds of years. In these two fantastic biographies, Summer Strevens composes the first studies into both women since the post-execution salacious biographies used to tarnish and punish even their memory. Mary Channing was convicted of killing her husband Thomas through mercury poisoning and found herself burned at the stake in 1706. Bateman was a serial con-artist, pretended to have supernatural powers and poisoned multiple people, although she was only convicted for one murder. Historical research regarding women like them is necessary and their voices, no matter how we might approach them morally, need to be heard. The fact is that for countless historical female criminals, their crimes, unlike the same crimes done by men, had to be emphasised as both an abhorrent revolt against a quiet virtuous woman’s rightful place under men and equally a sign of women’s inherent sinfulness through their connective to Eve.

The way in which both Marys were judged and sentenced shows this. Strevens, in Burned At The Stake, comments that the societal impact of women’s subordination even resulted in “modes of executions” personifying “the inequality of the sex”. Mary Channing was not executed for the murder of a spouse as a man might have been. She was convicted of petty treason. This nasty sentence was attached to women who killed their husbands. By doing so they went against the natural gender hierarchy, and with state and the household traditionally ruled by male authority figures, they were deemed to be traitors on a fundamental level. The worst form of woman.

While a man in Mary’s place would have been hanged, she as a petty traitor instead was sentenced to burning. In 1706 this allowed the condemned woman to be strangled before her body was incinerated but this did not always ensure the woman was dead. Catherine Hayes, another woman killed this way, survived in agony until her brains were “dashed in”. Mary seems to have been alive when the fire began too.

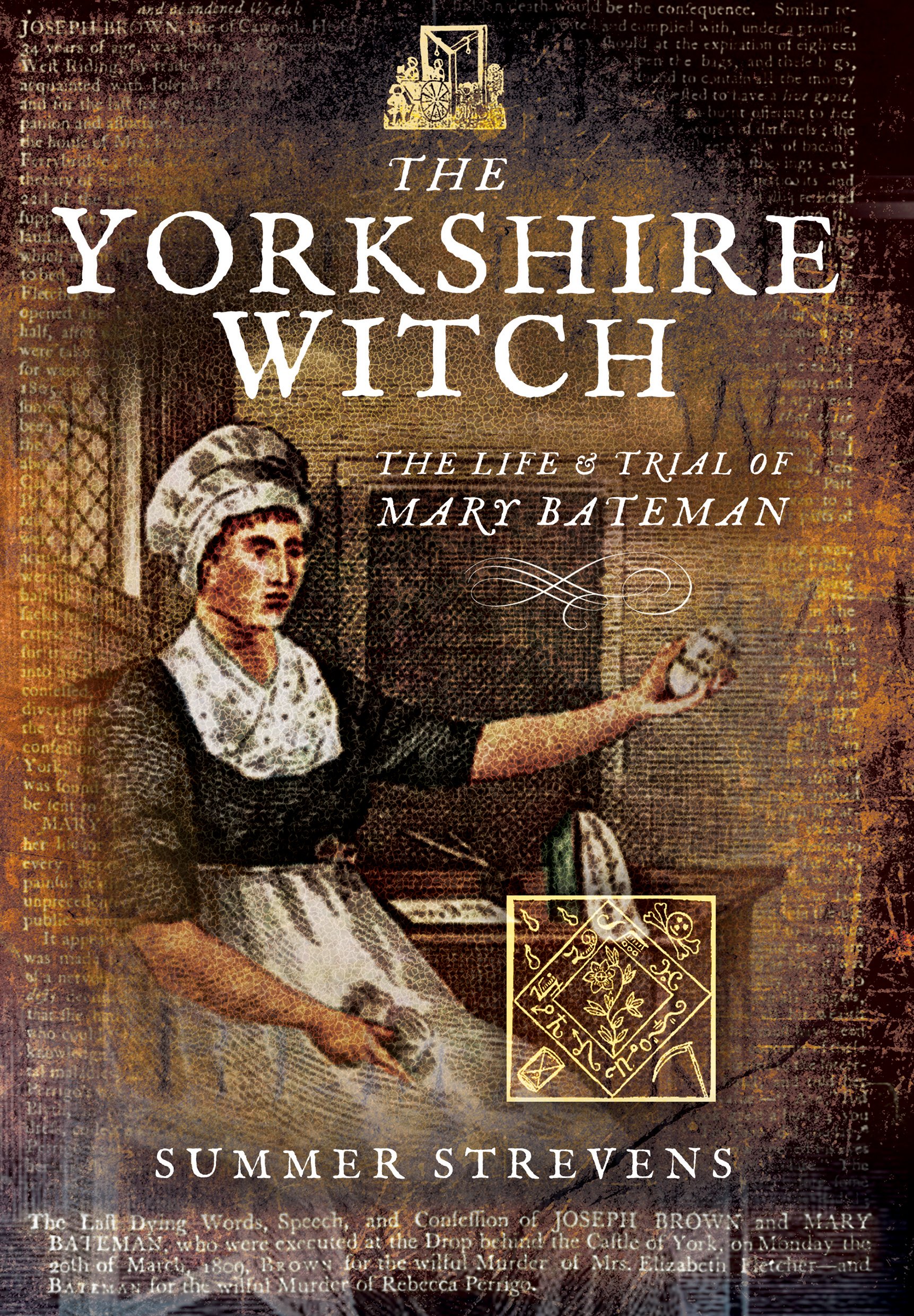

Mary Bateman was executed in 1809. She was hanged for the murder of a Rebecca Perigo, but had committed more crimes besides. She might be seen as a serial killer today. Bateman poisoned multiple people including two Misses Kitchin, Quaker sisters, and their mother. She was an abortionist with many women seeking an end to pregnancies likely counted among her victims too. She was also a con-woman who through “artifice and deleterious skill” deceived people into thinking she had supernatural powers. Using the folk memory of witchcraft, Bateman pretended to be a fortune teller, clairvoyant and able to provide magical cures. While Channing was deemed a petty traitor for murder, in Bateman’s case she was executed for murder, but nicknamed “The Yorkshire Witch”. Only someone of maleficent magical means could be so evil. Some attendees at her hanging even believed she would use her powers to escape ,but ultimately this didn’t happen.

The lives and deaths of both women became centred around the acts they are believed to have committed, Strevens notes. A year after Mary Channing’s execution, the Admonitions to Youth, was published on her life, trial and execution. Her crime was explained and condemned with references to her Anabaptist origins, meaning she was baptised only in prison awaiting execution, making the work claim her parents had been negligent in “the improvements of a religious education”. Her party girl lifestyle during her teens, a period she “chiefly spent in pleasure”, tainted the view of her in her trial as well. Married off to Thomas Channing, she supposedly poisoned him with mercury within a year.

Pleading her belly gave Channing a short reprieve. In a very pagan manner she was to be burned on on the floor of Dorchester’s ancient Roman amphitheatre called Maumbury Ring. Her death had to wait until 5pm as the under-sheriff wanted to finish his tea. A huge crowd of 10,000 people came to watch Channing die, weak following childbirth and still only 19. She was believed to be alive when the fire was lit due to the strangling being botched. Thomas Hardy, author of works like Tess of the D’Urbrevilles, who portrayed “fallen” women in compassionate, complicated and realistic terms despite victorian moral outrage, believed in Channing’s innocence and wrote in his Mayor of Casterbridge that likely, “Not one of those ten thousand people cared particularly for hot roast after that”. Hardy throughout his career who stand up for women like Mary Channing and decried the treatment of her in life and death, whether she was innocent or not. Strevens has took his torch and is enabling Mary Channing’s voice to be heard clearly for the first time.

The execution of Mary Bateman at York’s New Drop Gallows, happening 103 years after Channing’s in 1809, was an excuse for people to revel in violence. Bateman’s “vicious disposition” resulted in possibly a 20,000 strong audience, many from her home town Leeds or victims of her hoaxes. She was a witch in deed if not in nature to them. The biography on her The Extraordinary Life[…], published two years later in 1811 went into 12 editions, as people sought to understand her evil.

Strevens’s books are fantastic studies of women whose actions, bad or good, have faded from notoriety and memory into dust. As Summer describes herself both books are invaluable as they show historical women “were not just good or bad but motivated by personal and societal complexities and conflicts just as we are today”.