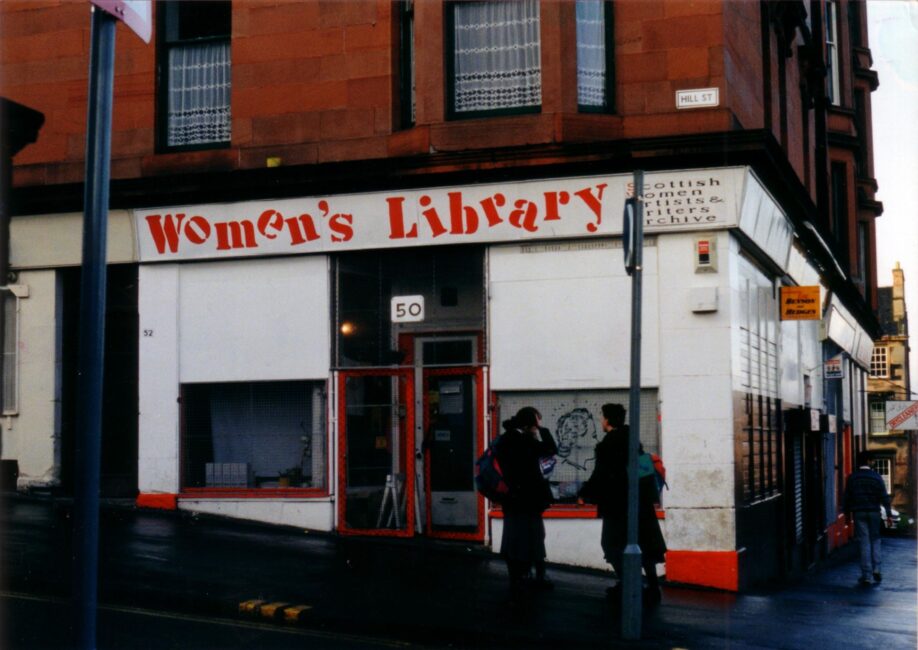

Rational Passions: Women and Scholarship in Britain 1702-1870: A Reader edited by Felicia Gordon and Gina Luria Walker is an important collection of the early written scholarship composed by women in Britain printed by Broadview press. It represents the wish that Virginia Woolf had in her A Room of One’s Own: “Therefore I would ask you to write all kinds of books, hesitating at no subject however trivial or however vast.” The early modern period saw different women of different religious and class backgrounds increasingly writing on a widening expanse of subjects and involved such women trying to create rooms of their own within different genres like history or the sciences, some choosing to forge their own feminine worlds of scholarship while others tried to enter the existing male spheres. Journals and reviews acted as a means of connection between women.

As the introduction notes women in public spheres had an uneasy position. Although celebration of female public-facing genius is present in Richard Samuel’s 1779 Nine Living Muses portrait of the Blue Stockings Society of Elizabeth Montagu, Angelica Kauffman and later those like Hannah More as scholars of different fields women had to embody both a public face and private decorum. Intellectual Refinement was an accomplishment, but should not be a career or it could lead to comments like William Wraxall’s on Mortuga in which he said that there was “nothing feminine about her” and that she was “destitute of taste”. Blue-stocking became a sometimes derogatory term for learned women after this society tying intelligence to frumpiness. How did women learn to navigate within the boundaries such terms allowed for good and bad? The first section consists of female historians who over the period contributed to historiography. The editors discuss how such women often used untouched archival sources and contributed to the growth of more biographical and social histories as well as focusing on figures as often shunned in history as emulated and widely wrote of. History could be a didactic exercise ,but some women tried to change history of women worthies into a domain that allowed female historical players in all shades of character to be represented like male actors.

An early female history pioneer discussed was Catharine Macaulay nee Sawbridge (1731-91).She was a political thinker, pamphleteer and educational writer in addition to historian. One of four children to John Sawbridge, a wealthy landowner, and sister to a member of parliament she was highly educated and involved in radical politics and although she could not read histories from the classical world in their original languages their translations drove her to explore in the modern day through the same concepts of “liberty” that the classic world exhibited in “its most exalted state” in her view. Her husband George Macaulay supported her in her writing with the first volume of her History of England from the Accession of James I to the Elevation of the House of Hanover appearing in 1763 and four more coming by 1773. In the collection it is extracts from her 1768 volume that are featured. It became a popular Whig counterpoint to David Hume’s History of England (1753-61) which was deemed a Tory text. Her popularity in a male form of political history was considerable, but eventually her radicalism lost her Whig support while the mocking personality cult created by her patron Reverend Thomas Wilson for her and a marriage to the twenty-six years younger William Graham when she was 47 acted as the death knell to her respectability and ended her ability to conduct a public personality in the same way.

Lucy Aikin’s “The Trial and Execution of Mary Queen of Scots” from the Memoirs of the Court of Elizabeth(1818) is another example. She was part of the Jennings Aikin Barbauld family who read widely in English, French, Italian and Latin. Although holding feminist views she deemed it private and not something she should publically advertise. Her section on the trials sets up and takes away the moralizing of female historical figures’ actions. Although she discusses negatively that Elizabeth took away Mary’s rights as “a sovereign princess” calling her the later Queen of Scots and tried her through commissioners despite Mary refusing the trial as an ‘absolute princess’ only triable by her royal peers she does acknowledge Elizabeth’s need to take this action. Mary had been endeavoring English fugitives to incite a Spanish Invasion, was negotiating with Rome and there was proof of her danger to Elizabeth. Aikin argues her work is a memoir on character more than a lofty history and although she discusses Elizabeth’s actions with judgements on her morality she states the “peculiar province of history” drove her to it. Elizabeth might not be a perfect character or woman worthy, but is allowed to be a full historical player not an a-historical lesson in morality in Aikin’s work.

Agnes and Elizabeth Strickland’s Lives of the Queen of England from the Normal Conquest (1877) features as a contrast and comparison to the earlier Aikin’s work both similar yet different. The sisters tried to base their history on documentary evidence and primary sources as much as possible in a period that made access for non-academics and women to access them. Their father had provided them with an equal education to their brothers with Latin, maths and history featured instilling academic self-sufficiency in their work. They used the British Museum, Elizabeth learned Paleography and in 1837 Agnes asked for access to state papers. Looking through historical biography at figures until then ignored like royal women and children, equally exemplary or notorious, they opened up commercial printing possibilities for other women writers. Besides thorough scholarly dedication they also engaged in the publishing of their writing with Elizabeth establishing many of their publishing contracts. As Agnes said “truth” lied “not on the surface”, but required effort. The extract featured shows this as it focuses on Queen Mary of Scot’s execution too using their discovery of Cottonian Library documents which their believed proved that courtiers like Burleigh had proceeded with the execution and forged Elizabeth’s signature “transferring the stain of that murder from her to her ministers”. We know now this is untrue, but it had backing at the time strengthened by their work. Unlike Aikins this therefore gave Elizabeth a better moral reputation, but with backing.

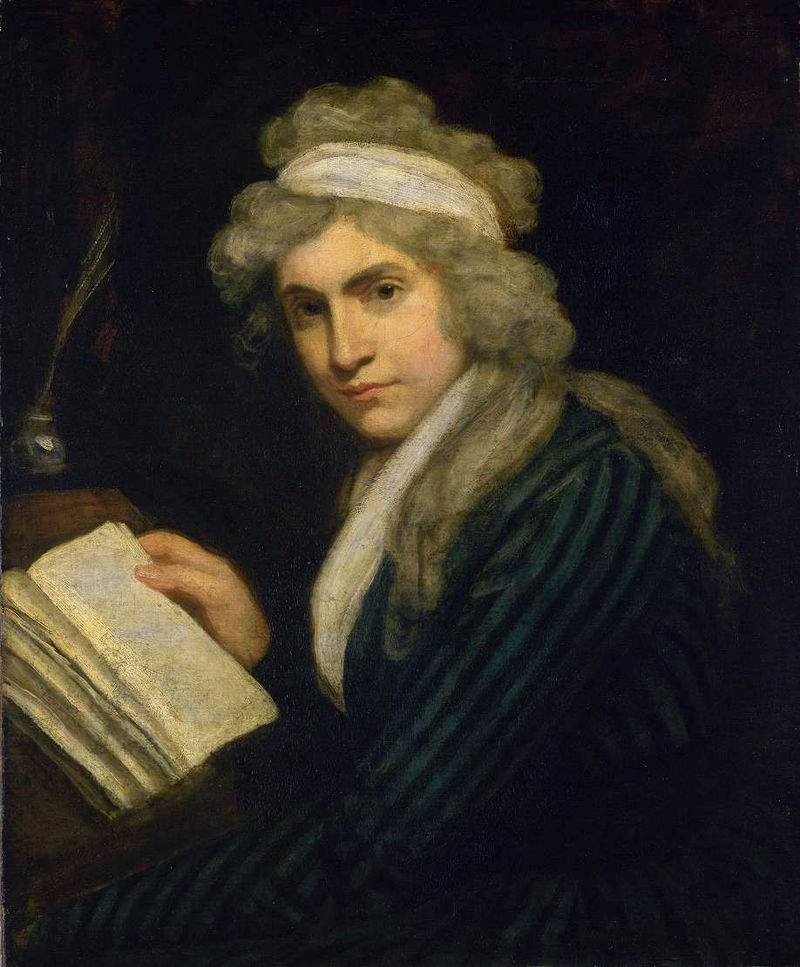

Finally, there is Mary Hays who is worth noting in this section. She became a Unitarian, was from a trading family and was inspired by Mary Wollstonecraft who she met and reintroduced to William Goodwin. She composed experimental fiction, reviewed novels for the Analytical Review, was publically feminist and published a collection of biographies of 288 women in six volumes acting as an alternative to the histories of great men. Women of all types were included be they adventurers, infamous, pious or more. It was judged as a serious text by contemporary reviewers ,but her inclusion of supposedly immoral women during the start of the moralistic 19th century had it judged as flawed. The connection and genealogy of all the vital scholars collected here is evident through one included figure which is in the extract here: Catharine Macaulay Graham who Mary Hays described as a “woman who by her writing and the powers of her mind” had reflected ‘credit on her sex and country”.

Part two within the work focuses on educational pieces by women which could often display feminist tendencies in and of themselves while part three is about philosophy and religion. Part four looks at female scholarly discourse of the period via art and literary criticism. Elizabeth Mortagu(1718-1800) is featured who used her position as gentry and her money connections to promote female learning and publication. A saloniere ,she was called the Queen of Blue Stockings, and produced the cited work on “The Writings and Genius of Shakespeare” (1769) which was the result of long study of, and attendance at, productions of Shakespeare’s plays. She was one of the first to enshrine Shakespeare and raise him to his current standing as perhaps the greatest writer to ever live. Mythologizing him was a longer process that we would believe today and was impacted by her thorough analysis of his compositions. A second critic mentioned is the pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-97) who was editorial assistant then review editior for the Analytical Review. Featured is a review of letters on education by Catharine Macualay Graham published in 1790. Like Hay she champions her as a “masculine and fervid writer” with “superior powers” of mind. In one of the last sections there are pieces of scientific and mathematic scholarship by women in perhaps one of the most difficult domains for women to engage with. Priscilla Wakefield’s Introduction to Botany(1796) and the amazing Ada Augusta Lovelace Byron’s Notes on Menabreas Memoir on Babbages Calculating Engines(1843) are particularly interesting.

Felicia Gordon and Gina Luria Walker’s masterful collection of female scholarship from 1702-1870 is therefore a must read which shows the expansion of women’s writing into wider and wider non-fictional areas. It shows their communication with and opposition to the contemporary masculine hegemony of scholarship and their influence on each other. Writing “all kinds of books” no matter how ‘vast” or “trivial” the period saw women truly create rooms of their own to study and understand the world around them while changing scholarship as a whole together.