Hello! My name is Giorgia, I am Italian and I am a Gender Studies MA student at Stirling University. I find the existence of a Women’s Library in Glasgow full of wonderful books and magazines both inspirational and enchanting, and I definitely did not want to miss out on the possibility of exploring this matriarchal and feminist shelter as part of a research placement for my degree programme!

The huge Lesbian Archive at the Glasgow Women’s Library allowed me to focus my research on two specific historical periods I have always been interested in: the 20s/30s and the pre-Stonewall era (How can one forget the image of a rebellious Sylvia Rivera pitched against homophobic cops in the New York of 1970! But above all, the marvelous, brave, and lesser- known Stormé DeLarverie, the black lesbian who had started the Stonewall uprising in 1969). My research placement in the library gave me the opportunity to read and work on two powerful and fascinating magazines printed in London during this time frame: Urania and Arena Three.

In this first blog I will direct my attention to the earliest of the two magazines, its editorial structure and aims. So, let’s talk about Urania!

Urania was a feminist and ante litteram (pre/proto) queer (the meaning of the term ‘queer’ is here employed in its original meaning coined by De Lauretis in 1991) magazine that came out three times per year from 1916 to 1940 with a double issue. It is important to keep in mind that Urania was not a publication intended for a large readership, but a highbrow collection of worldwide articles about women and gender to be shared within a small circle of female and feminist eggheads. The printing of this Journal remained private for twenty-four years and as Thomas Baty, alias Irene Clyde, points out in the Distributor’s note at the end of every edition: ‘Urania is not published, nor offered to the public, but [..] can be had by friends’.

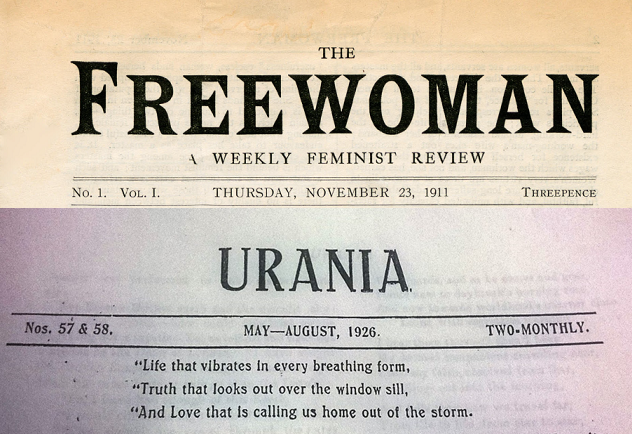

The magazine is presented as a bricolage of reprinted articles from other newspapers and periodicals from all over the world (especially Japan), pieces of biographies, autobiographies and poems. In addition to this, it is possible to find now and then in the publication, memorials or political commentaries written by Clyde. A revolutionary new feminist belief promoting peace, equality and the elimination of gender distinctions underlies the magazine (quite radical eh?). It is in many ways similar to another wonderful feminist magazine published in London for a couple of years a little earlier in the century: The Freewoman (1911-1912). Both publications distance themselves from a feminism that focuses only on voting and in support of war (Do you remember Emmeline Pankhurst and the ‘White Feather’ feminists?), rather they advocate for a society of equals, ‘of masters, among masters’ (1911, p. 2).

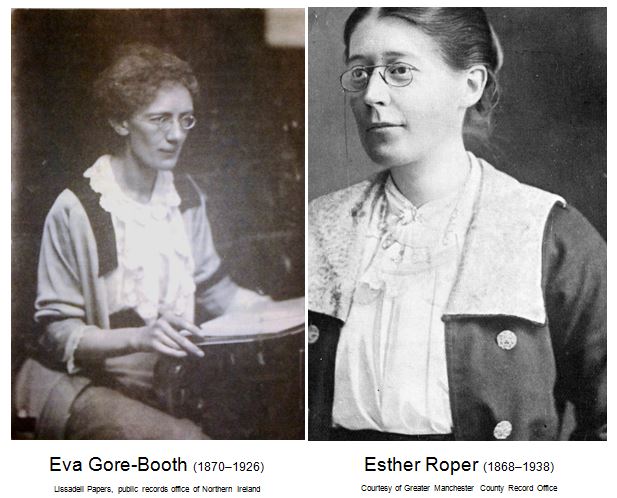

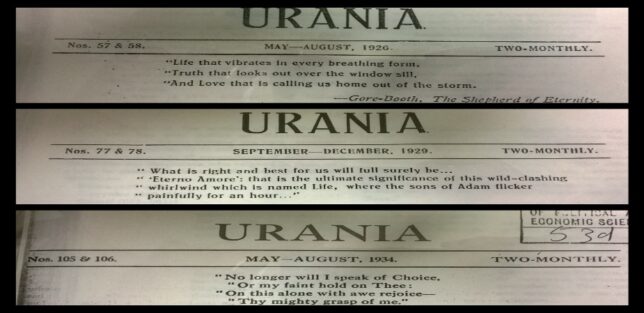

But coming back to Urania and its structure, there are two things that mostly caught my eye. One it is the consistency in the number of pages of every issue which averages at 12 and shows the texture of the project; the other is the repetition of the same Eva Gore-Booth quote on the cover of the magazine. Eva Gore-Booth, mind and source of inspiration of Urania, along with her long-term partner and friend Esther Roper, was a feminist and poetess strictly tied to spirituality and ancient Christianity. Gore-Booth’ s bond with feminism and a religion without dogmas is pretty evident in her words and can be deduced from the quoted poem on the cover; words considered a mantra to follow by Urania’s editors.

A curiosity? The quote remains the same from 1926 to 1928 but changes between 1929 and 1930 to a piece from an 1844 Carlyle-Sterling letter. Furthermore, the quote comes back unchanged on the cover of 1933 to turn again from 1934 to September/December 1935 into another piece of the same poem by Gore-Booth and eventually reappears alike in January/April 1935 until 1938.

I assume that the editors of Urania, decided to change the quote in 1929 to underscore their ethical and political aim: the creation of a society based on love and solidarity; a belief that needed to be stronger under economic depression and new dictatorships.

In the following blog, I will take into account the specific contents of Urania where a powerful, pacifist and feminist thought arises. In these articles it is pointed out how much Fascism and violence divide humanity and harm feminism (sounds sadly current eh?).

Further readings:

Oram, A. (2001) Feminism, Androgyny and Love between Women in Urania, 1916-1940 in Media History, vol. 7 no. 1, Northampton: University College Northampton.

O’Connor, S. and Shepard, C. (2008) Women, Social Change in Twentieth Century Ireland: Dissenting Voices? Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Inspired by the bond between feminism and pacifism at the beginning of the Twentieth century? Why not reading ‘Pensées d’une Amazone’ by the poetess Natalie Clifford Barney?