I’m Alice, and I currently work at GWL as a sessional worker, working specifically on the collection which is popularly known as the Lesbian Archive. My job is to work with volunteers to list and research the collections, as well as to create new online and offline resources which highlight the collections and make them a little more accessible.

Though known as the Lesbian Archive, the collection is actually a pretty wide ranging collection which takes in a range of LGBTQ histories from the early twentieth century right up until the present day. It also charts some of the key campaigns and concerns affecting LGBTQ people and politics through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. To find out more, you can visit our Lesbian Archive collections page, and check out our new online insight pages which we’ll be launching later on in February to celebrate LGBT History Month!

Choosing something to highlight for GWL25 from this enormous collection has been pretty hard as you can imagine! The collection has a very large and print and publication collection, and it has been this which has been the biggest revelation to me whilst working on the archive this year. We’ve been able to unearth publications and journals that we didn’t even know we had, so I’ve chosen to highlight one of our new finds, and definitely one of my favourites!

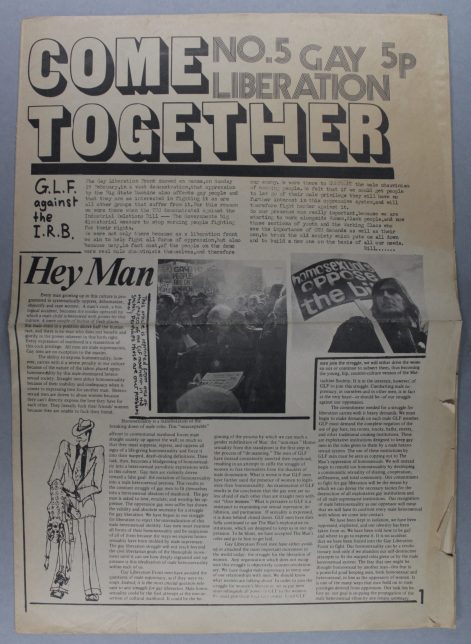

Among the new finds was issues of the newspaper of the Gay Liberation Front, Come Together. Based in London and produced by the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) media group, Come Together charted the efforts of Gay Liberation in the early 1970s. Stylistically the newspaper is absolutely incredible, and was assembled through collaging techniques often combined with had drawn artworks, cartoons and sketches.

In Issue 5 of Come Together (1971), we see some of the key concerns of Gay Liberation in the early 1970s. It foregrounds the complicated relationship which early Gay Liberation had with other social justice movements, in particular the Women’s Liberation movement and working class movements. The front page for example covers a confrontational action undertaken by GLF as both an act of solidarity with the TUC over their opposition to the Industrial Relations Bill – an act of solidarity which would prefigure the solidarity between Lesbians and Gays and striking workers in the 1980s, but which throws up the slightly troubled path that these acts of solidarity had initially:

We were not only there because as a liberation front we aim to help fight all forms of oppression, but also because many, in fact most, of the people on the demo were real male chauvinists themselves, and therefore, our enemy…

Elsewhere in the paper, other actions are also detailed. An action in the Imperial College student union, directed against rowdy misogynistic and homophobic rugby playing students, details members of GLF and the Women’s Liberation movement dragging up and goading the students by kissing each other and ordering beer at the bar. When confronted with a hose pipe, the protesters stood defiant – “It’s only water girls, come on and enjoy it and we did. The places was wrecked, water everywhere as we stood, silent and defiant until they advanced with baseball bats and physically threw us out”.

On the back page a demonstration against the publisher of the book “Everything you wanted to know against sex but were afraid to ask” by WH Allen is described – an action which spoke to the anti-psychiatry motivations of the GLF. This desire to eliminate pathologising, oppressive and unethical medicalized and psychosexual interpretations of homosexuality is echoed in many other LGBT publications of this period notably publications like Arena 3 and The Ladder. The issue was so central to the early efforts of Gay Liberation that the GLF even had its very own anti-psychiatry action group.

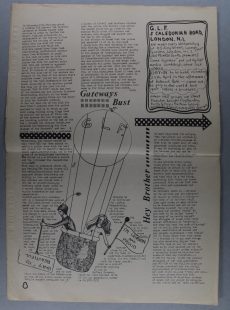

The efforts of the GLF to campaign against the policy of one of the oldest and most iconic lesbian bars in London, The Gateways Club, which had banned politics is also reported on. The Gateways which had been in existence since 1945 had long been a bastion of Butch/Femme dynamics amongst its Lesbian clientele. Butch women would be men and femme women would be women. To many in the burgeoning Women’s Liberation movement as well as the GLF, these dynamics were deemed to be a reinforcement of patriarchy – a regressive and apolitical role play. The action against The Gateways involved the peaceful protest of the club, and the distribution of political material in the form of GLF flyers and literature in the club as well as engaging members of the club in political conversation. The protest was greeted with heavy handed policing, and protesters were handed hefty fines and court costs of around £8 (over £100 in todays money). Butch/Femme would become repoliticised in LGTBQ politics, but the action says much not just about the politics of the time, and the ways in which the politicisation of sexuality was not a universally welcomed phenomenon for some.

One of my favourite articles is an incredible letter sent in by a drag queen entitled A Queen Is Person Really. It is a personal account of the exclusion felt by drag queens in movements like the GLF, where increasingly values of camp and effeminacy began to be sidelined, suppressed and diminished. The queen writes:

I am very politically minded and very ‘aware’, so I enjoy the lively GLF meetings and get quite excited when someone stands up, red faced and shouts back at someone else. Then someone says something about screaming queens – BANG – that hurt. I tell myself that queens have a part to play in GLF, and society at large, and all my friends agree. So what am I really worried about? Can anyone tell me??

The letter reflects on something which I think is reflected in many other publications, writings and resources in the archive. Namely about the danger of not embracing the difference within our communities, not just the LGBTQ community. The danger of homogenising radical movements ultimately ends in loneliness and isolation for some. Echoing parts of Sylvia Rivera’s incredible speech during one Pride March in the 1973, the letter speaks to concerns that many had from an early stage about respectability politics and assimilationist politics creeping into a movement which had had to physically fight against the state for so much.

These are still conversations being had in the LGBTQ community today, and you can draw plenty of parallels between the concerns of a publication like Come Together and contemporary LGBTQ politics, particularly around issues connected with misogyny or sexism, classism or trans exclusion. LGBT History Month is an amazing opportunity for us to reflect on these incredible documents from the past, like Come Together, not just to remember or reflect on what has come before, but to help frame and contextualise our activism today and in the future.