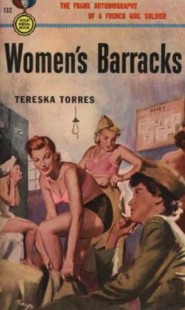

A book’s cover acts as the first touchpoint we have with the story and its meaning, drawing us in and providing us with a first impression which either makes or breaks our choice in buying/reading. This was never truer than with the novels of pulp fiction, where the role of the cover was paramount to the success of the genre itself. With such a massive and rapid turnout of novels, the covers were crucial in guaranteeing readership, acting as an identification tool for those looking for a particular genre. And so ‘the books were packaged to move, flashing their wares like an open-raincoated exhibitionist – voluptuous cover art, sweat-soaked blurbs and titles that had no time for the niceties of evocation or double entendre’(Server cited in Keller, 2005, 398). Sensationalism was key, and expected, not only as a marketing tool, but for overall reader experience.

Women’s Barracks and the visual imagery of lesbian lit

The deciding role of the pulp fiction cover and its power in manipulating reader perception of the novel

itself can be viewed with GWL’s collection of lesbian pulps, particularly with the different editions in the archives of Tereska Torres’ Women’s Barracks (currently on display as part of the Women in Pulp Fiction exhibition). Published in 1950, Women’s Barracks is hailed as the pioneer of lesbian fiction, and despite Torres’ own reluctance to assume the title of the ‘literary queen of the lesbians’(Torres quoted in Lichfield, 2010), the semi-autobiographical account of women serving in the Free French in London during WW2 has acted as an influential facilitator of lesbian identification since its first publication. Serving up an array of different options for women, with its independent female characters pursuing work, relationships, with both men and women, and unconventional living situations, Women’s Barracks provided a necessary form of representation for lesbian readers in a cultural environment that forced their sexuality underground, or denied its existence.

The Changing Face of Lesbian Pulps

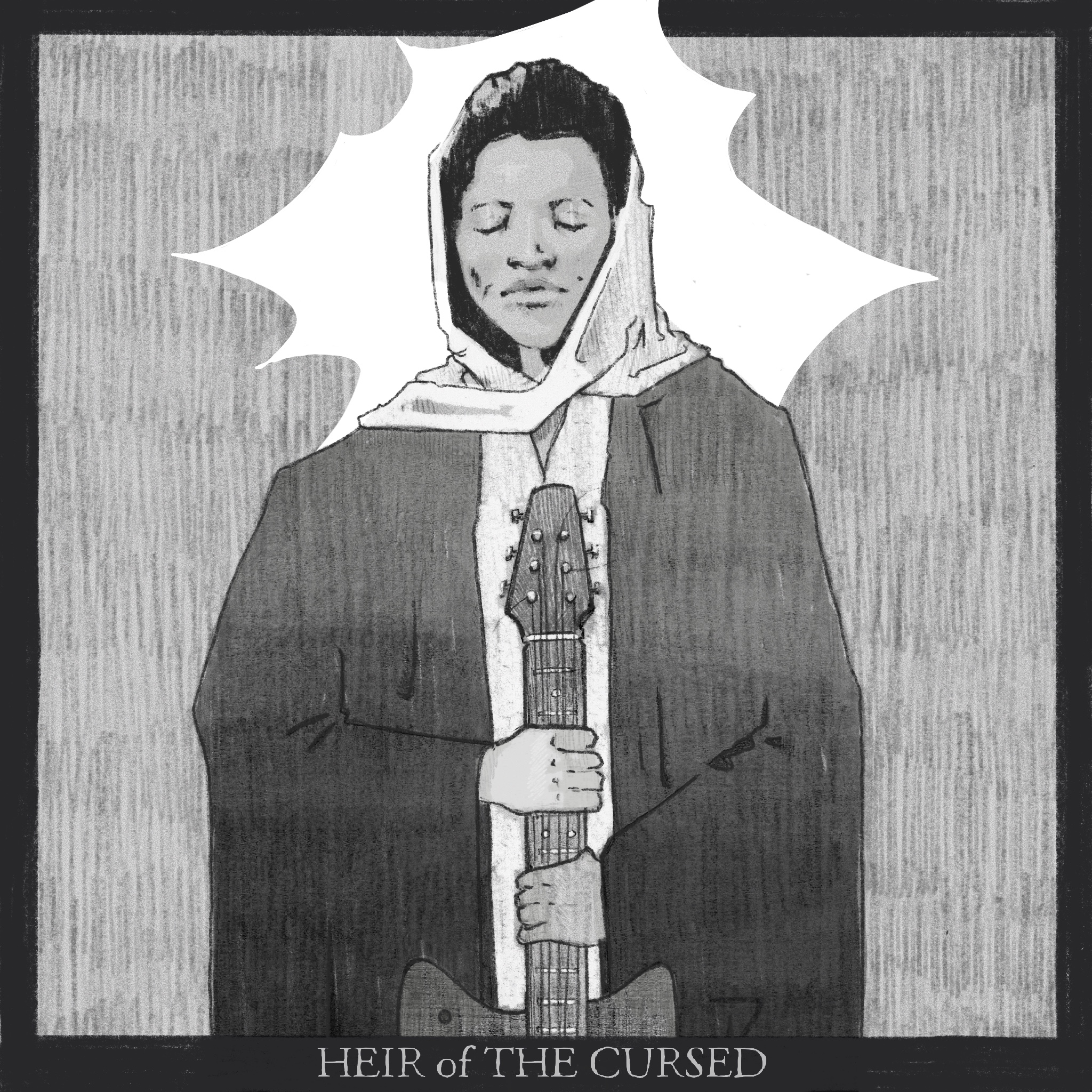

And yet the change in the book’s cover from the original artwork of 1950 through the numerous reprints of the 60s and 70s reveals a social shift in the way lesbian pulp literature was marketed and the women in the stories were perceived. In the 1950s original a locker room scene depicting a group of women changing into their uniforms emphasises the all female setting of the novel (a common convention of lesbian pulps) and thereby acts as an identifier for lesbian readers. The cover, although slightly suggestive for the period is not as outrageously sensationalised and titillating as those of pulps geared towards male heterosexual readers. The look shared between the two women in the foreground seems like a candid scene, and contrasts with the more staged style found in ‘virile’ lesbian pulps written by men/for men.

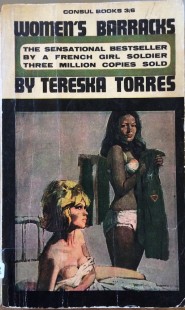

Glasgow Women’s Library’s collection of Women’s Barracks editions begins with the 1964 reprint of the 1962 Consul Books publication, released near the end of the ‘golden age of lesbian pulps’ (1950-65). Like the original cover, this scene of two women in a state of undress seems less staged and sensational than those for male readership, which suggests a sense of inclusivity for the reader. However, it does present certain readings of the lesbian pulp genre not found in the original cover. Whereas in the 1950s original the lesbian ‘hint’ is through an exchange of a glance, this cover is explicit in its sexuality. Additionally, the female body is far more objectified in this version than the previous. As the market for lesbian pulps was overtaken by the demand for those of male pornographic fantasy in the mid 60s, this slightly more titillating cover could be seen as reflective of a need to keep up to speed with the eroticised commercialisation of lesbian identity.

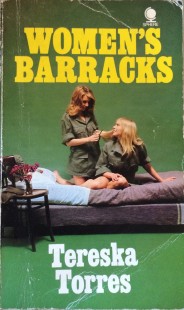

This commandeering of the lesbian pulp genre by male writers and male readers, and the rebranding of lesbian fiction as that of ‘wish fulfilment stuff, pure erotic daydreaming’ (Vin Packer cited in Keller, 391), can be seen with the final Women’s Barracks edition in the GWL collection, published by Sphere Books in 1972. The lurid green photographic cover has the air of a deliberate staged scene, and although less explicitly sexual the playful ‘sleepover’ vibe of the two girls in khaki army tunics playing with each other’s hair on a bed suggests an element of voyeurism and male fantasy more profoundly felt than in the other examples.

Whereas in the earlier editions where the intimacy of the cover scene invited the lesbian reader to involve herself in the story, this edition shows a scene that is distanced from lesbian experience, provided almost exclusively for the male gaze. Therefore this cover appears far less loaded with meaning than the others. Whereas the looks and exchanges between the women on the earlier editions are of desire, love, even slight resentment, this cover seems muted in its emotion (and thereby its commitment to representing lesbian relationships as complex).

Despite the changing nature of the Women’s Barracks covers over the years, the visual imagery of the lesbian pulp genre remains an important tool in understanding the nature of female representation in wider pulp fiction and also the public opinion towards female relationships during a period of immense social change.

Sources

Keller, Yvonne, ‘’Was it right to lover her brother’s wife so passionately?’: Lesbian Pulp Novels and U.S Lesbian Identity, 1950-1965’, American Quarterly 52(2) (2005) 285-410

Lichfield, John, ‘Tereska Torres: The reluctant queen of lesbian literature’, The Independent, 5 February 2010