The 13th August 2015 marks the 135th birthday of Mary Macarthur, a woman who fought tirelessly for the rights of women, of all classes and occupations. Born to a Conservative family and educated in Glasgow, it was at the age of 21 that Mary attended a speech by John Turner discussing the poor conditions of workers and the manner in which they were treated by their employers, thus a trade unionist was born. Two years later, in 1903, Mary made the move to London where she swiftly became the Secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League. Not only had she defied her family’s political background but she was firmly opposed to the politics of both the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) as she sought franchise for all women, not just particular groups of women such as the upper classes. In her campaign for universal suffrage Mary established the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW) in 1906, with the aim to organise women in the movement against the sweated industries and for the introduction of a legal minimum wage.

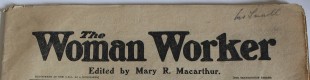

This Federation fought for and accepted all women, of different classes and nationalities, which can be seen in the publication of The Woman Worker which sought to further the work of the NFWW through a variety of articles, commentaries, advertisements, and anecdotes. The archives of Glasgow Women’s Library hold 9 editions of this periodical, which quickly became a weekly newspaper due to the overwhelming popularity with men and women throughout Britain. In the very first edition Mary Macarthur made an editorial announcement which proved to be her and the Federation’s mission objective:

‘To teach the need for unity, to help improve working conditions, to present a monthly picture of the many activities of women Trade Unionists, to discuss all questions affecting the interests and welfare of women. Such, in brief, is our aim and purpose.’

Reading through the issues of The Woman Worker one is struck by the combination of the serious, political issues with the light-hearted witty insights. Macarthur and her team discuss both work and home life, investigating every aspect of their audience’s life in order to fully integrate feminism and the fight for suffrage into daily life.

The Woman Worker achieved this by documenting world news, discussing women in fatal trades, advice columns with doctors and lawyers, serialised stories, dress patterns, updates on the campaign for suffrage, and fashion advice such as advocating not wearing a corset. In the editions that this Library holds one can read the public outcry of support for Daisy Lord, a young woman charged with the murder of her illegitimate child. Or the account, in 1909, in support of a thirteen year old girl who wished to become a boy and thus had a suit fitted and her hair cut short. This blend of widespread political issues with day-today domestic accounts allows for every women of every lifestyle to connect to the issues raised and to lend importance to their daily life.

Mary Macarthur was a defiant and bold figure who by the time of her death in 1921, at the young age of 41, had organised over 300,000 women into a trade union movement. The focus in her work, including The Woman Worker, was the creation of a community amongst her readers; not only does the newspaper focus on a personal level at women and their lives but encouraged and aided putting readers in touch with each other in the aim of furthering the cause for suffrage. The Woman Worker is at its core a celebration of all women in all pursuits; their work, art, and domestic life, and it was Mary Macarthur’s light and independent voice which increased the popularity of The Woman Worker and created such an effortlessly informative and entertaining read, for readers now just as much as over a hundred years ago.