On 15th January, I was pleased and privileged to have the opportunity to join Rachel Thain-Gray (Development Worker for the Mixing the Colours project at Glasgow Women’s Library) at the first Community Action Research in Tackling Sectarianism Co-Inquiry, hosted by the Scottish Community Development Centre (SCDC) at the IET Teacher Building on Glasgow’s St Enoch Square.

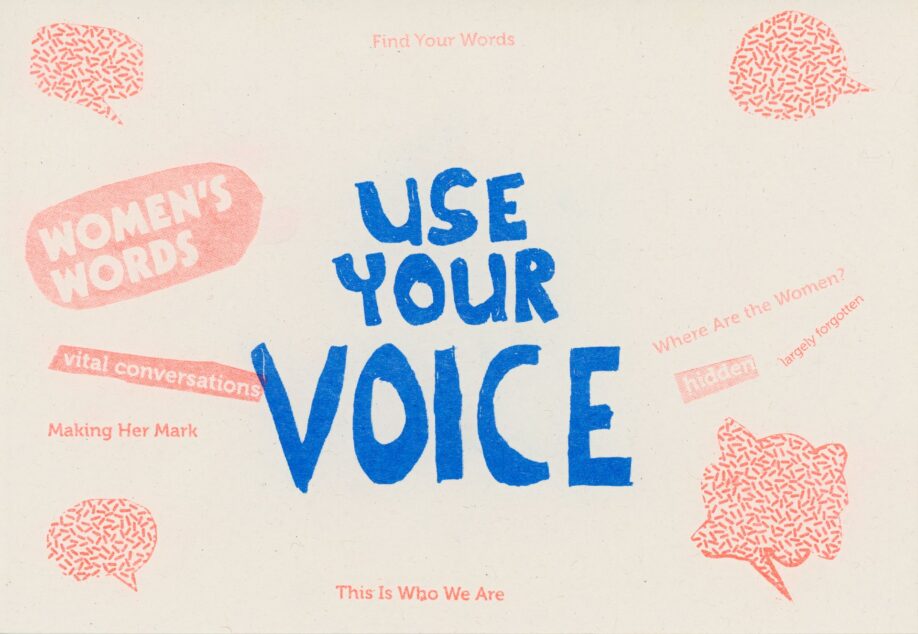

The Library’s Mixing the Colours project was created to enable women to speak about intra-Christian sectarianism – a topic which is usually discussed exclusively through the language of male thought, identity and activity. Where women are considered within the context of sectarianism, much of what emerges tends to focus on the gender as a passive rather than an active force (for example, as the victims of domestic abuse), with the result that narratives of this kind neglect the active roles that women play in the home, in education, in the wider community and in government. Ultimately, in all of the many environments in which sectarianism is both nurtured and tackled, women are demonstrably not simply passive forces. We can address this problem first by acknowledging the major role played by women in these spheres, and secondly by widening participation and dialogue so that women are actively encouraged to contribute to the debate. It is this contribution that the Mixing the Colours project seeks to facilitate.

The Community Action Research in Tackling Sectarianism Co-Inquiry was the first in a series of meetings of representatives from organisations with an interest in sharing reflections, resources and experiences of sectarianism in Scotland. Several prominent community-based organisations attended, including Community Links South Lanarkshire, Yipworld, Xchange Scotland, Pilmeny Development Project, Inverclyde Community Development Trust and Getting Better Together. In spite of the considerable range of organisations involved, the number of attendees was limited enough to enable informal and candid discussion and meaningful workshopping.

Upon arrival, we were each given the opportunity to introduce ourselves and our roles within our organisations over a coffee – so that by the time we came to split into two smaller groups to share ideas through workshopping, we felt comfortable and prepared for frank discussion. After some brief warm-up and introductory exercises, we agreed a ‘baseline’ of best practice for the activities which were to follow – points such as respect for differing points of view, making room for the learning styles of others and being open to learning from the input and experiences of others became central to our agreed ‘baseline’.

Ahead of the meeting, we were asked to read some specified texts on the history of sectarianism in Scotland, and to bring along three ‘items’ to the co-inquiry which had relevance to our experience and understanding of sectarianism from a personal, professional and reflective point of view. These items, considered in conjunction with the items and input of colleagues within the group, would form the basis of a ‘picture’ of sectarianism – this might take the form of a collage, map, flowchart or some other agreed visual representation of the topic. The background reading was complex, but really ensured that we came to the meeting with a common foundation knowledge of the historical and cultural ‘roots’ of sectarianism in Scotland, and the request for three items from each contributor created a fantastic initial talking point – contributions included service medals, old photographs, a graduation teddy, poetry, a school tie, and even a kitchen scale!

Our group was able to seize upon several areas where we felt sectarianism (and potential solutions to it) could be found, and how it manifests itself. Particularly striking was the fact that the topic of ‘football’ eventually emerged as the least central and revealing area of discussion (which is perhaps indicative that the discussion of sectarianism would indeed benefit from moving away from traditionally masculine, ‘gender-normative’ frameworks). We eventually concluded that all of our ‘aspects’ (politics, education, history, football) were offshoots of one key idea – identity. We spent several hours discussing our own interpretations of what feeds into identity, and I found it particularly interesting that the conversation often returned to the socio-economic factors which can lead people (and particularly younger people) into ‘toxic identities’ – that a person who feels disenfranchised within wider society may be inclined to seek a sense of belonging in a more sectarian environment. We examined the differences between ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ identities, how different identities co-exist (or fail to co-exist) within an individual, and how much of our identities are the result of nurture and external influence.

We concluded the day with discussion over a buffet lunch, and shared some reflections on the day which will form the basis of future co-inquiries. We were asked to spend some time before the next co-inquiry considering the issue of sectarianism within the context of certain ‘categories’, including gender, religion, culture, history, economics, education and community. In order to enable us to research and reflect more widely, we were each asked to focus on one or two categories which are of particular interest to us as individuals and/or to our organisations. As a writer and Glasgow Women’s Library volunteer, I chose to focus on ‘gender’ and ‘education’ – the first because I feel that extensive engagement of girls and women in the discussion of sectarianism is overdue, and the second because I believe that education is the ultimate mechanism by which we enable people to move out of prejudice and into a wider appreciation of their society and community.

I left this first co-inquiry feeling that I had really broadened my own knowledge of sectarianism in Scotland, and that I had been able to share and network with a group of people, each of whom had their own very unique outlook and experience to relate. This can be an extremely overwhelming subject – when examining sectarianism, it very quickly becomes apparent that it is an issue which cannot simply be tied down either to religion or to football culture. Having the freedom to view the topic through a range of ‘lenses’, in an open and non-judgemental environment, gives rise to some really original ideas about how communities can begin to tackle sectarianism. I look forward to exploring these ideas further, both through future co-inquiries and as a volunteer for the Mixing the Colours project.

You can find out more about the Mixing the Colours project here, or contact Rachel Thain-Gray at rachel.thain-gray@womenslibrary.org.uk.

Rebecca Jones