by Niamh Carey

When we think of feminist theory, it’s likely that Simone de Beauvoir or Judith Butler come to mind. These giants in feminist thought added an innovative voice in the discussion of sex and gender within their respective time periods, and understood the intersecting nature of culture, perceived biological ‘facts’, and gender identity.

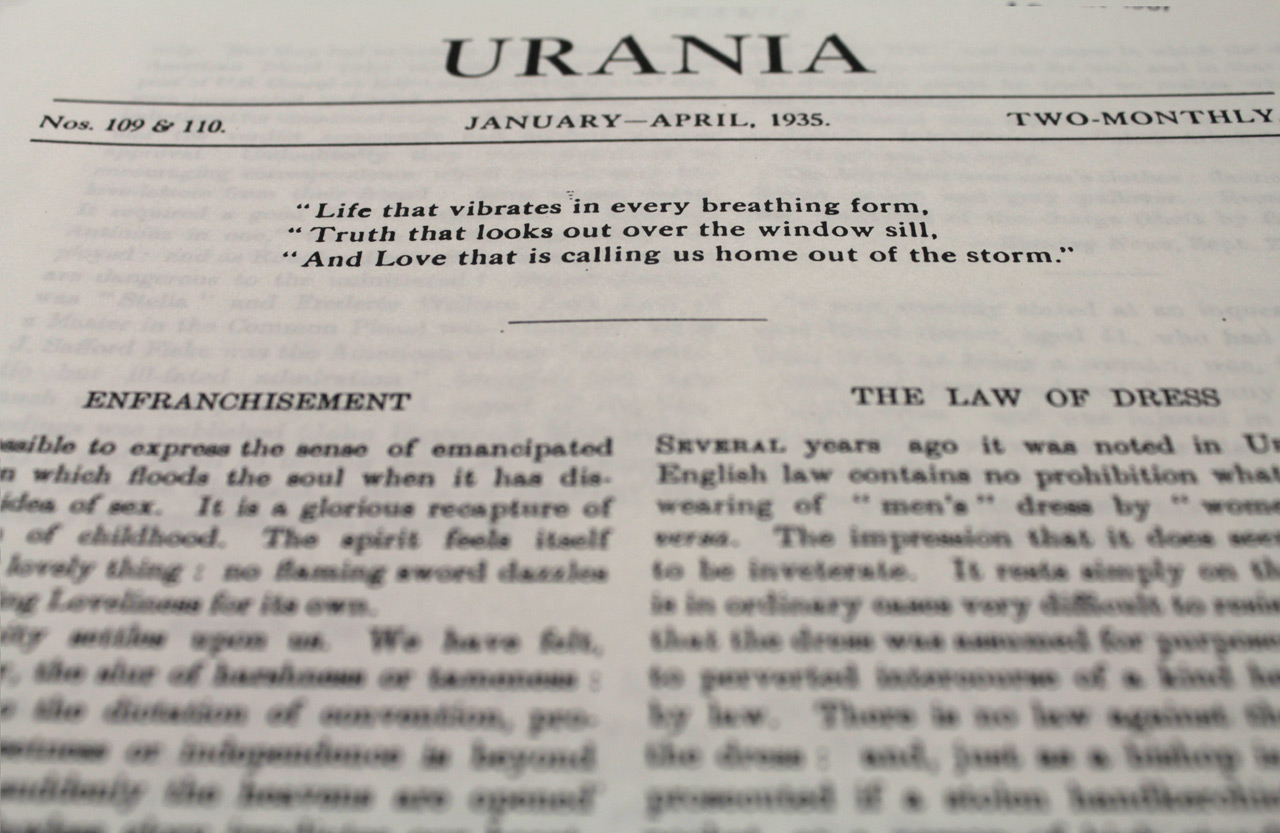

But decades before Beauvoir and Butler were making waves, a cluster of writers in England were already highly sceptical of the term ‘gender’. ‘Urania’, a little-known journal published between 1916 and 1940, made it its mission to debunk the very notion of ‘sex’. According to its statement of intent, “there are no ‘men’ or ‘women’ in Urania”i, and what follows over the next twenty years is a collection of articles from across the world that seek to undermine gender stereotypes and promote the ‘abolition’ of gender. Telling tales of sexual ‘rebels’ and gender-defying acts, the publication was an education: it adopted an expansive and ambitious narrative that left existing notions of gender and sexuality at the door. Pretty novel content for 1916.

The journal was set up by Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper, partners in crime both romantically and professionally, as well as Irene Clyde (also known as Thomas Baty), a transgender lawyer and scholar. Gore-Booth and Roper, being two highly intelligent, independent, and (worst of all!) lesbian suffragists, were social outcasts almost by definition, and made it their life’s work to undermine exactly what it was that made them seen as socially ‘rebellious’. Together with Clyde, they identified one factor to be the key perpetrator: the notion of inherent difference between human beings. They believed that ‘difference’ was a highly dangerous concept, and had been established through the creation of the (false) categories of gender. Its statement of intent claims that Urania “denotes the company of those who are firmly determined to ignore the dual organisation of humanity in all its manifestations”ii, and instead seeks to undermine the two “warped and imperfect types”iii that result from this duality. Indeed, a constant fight against this duality can be found on every page of the journal.

Flick to any page within Urania and surprising and fortuitous stories will be found aplenty. In the 1926 spring edition, a newspaper excerpt from China tells the tale of a wife who discovered that her husband was in fact a woman, but kept it a secret until his death.iv At another point, a Japanese article reports that it is common for young Japanese girls to engage in romantic relationships with each other.v The 1928 summer edition informs us of a “world’s women welfare directory” arising in India, which intends to unite women globally.vi The same issue reports a girl in New York who disguised herself as a man so that “she might the better make her way in the world”, in an article entitled ‘Women as Men’.vi These examples all offer a challenge to preconceptions of ‘fixed’ gender: of what a ‘man’ and a ‘woman’ is, how each should act (respectively), and the seemingly ‘static’ nature of the two.

Urania boldly claims that equality between the sexes cannot be truly possible until the notion of fixed gender categories is turned on its head. It believes that no measures of emancipation for women at the time would suffice, because the suffragist movement did not recognise the socially constructed nature of gender. In essence, equality cannot be achieved as long as the categories of ‘man’ and ‘woman’ are alive, as the notion of ‘difference’ has been born from the creation of such fixed categories. It recognises that human beings are incredibly eclectic, diverse and dynamic creatures; thus to have their behaviour dictated by what sex they belong to prevents all individuals (from both sexes, but particularly women) from achieving their full potential. In today’s society, where women are still chastised for not being ‘feminine’ enough and men are constantly under pressure to vindicate their ‘masculinity’, it is clear that Urania’s message still holds strong relevance to us.

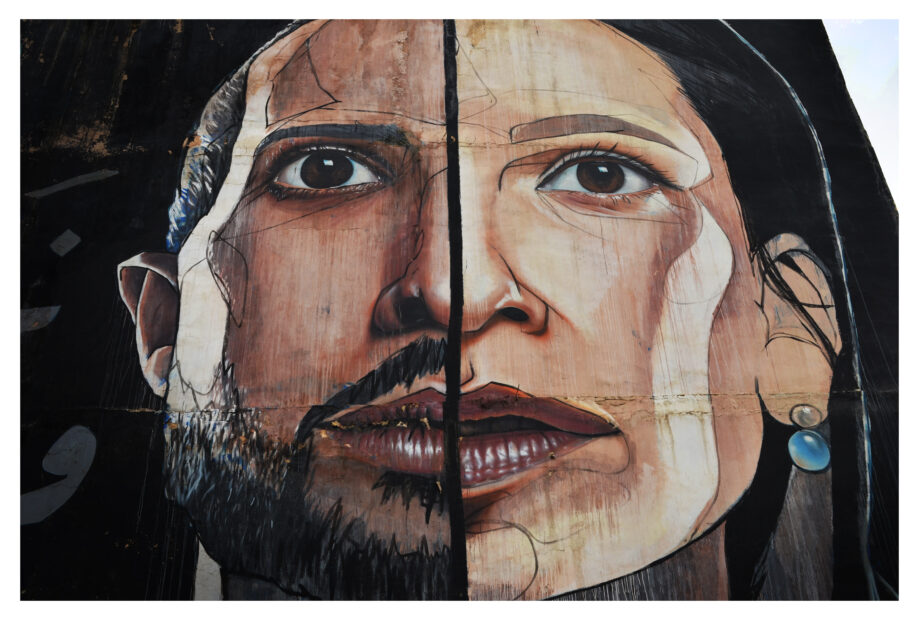

The publication, though focusing on gender and sexuality, draws attention to the fact that we live in a world of binary opposites. Whether these be ‘man’ versus ‘woman’, ‘good’ versus ‘bad’, it seems that the human mind finds comfort in categorising the world into simplistic boxes. But this has real social consequences: categories of race, gender, and sexuality are constructed on the basis of two binary opposite groups, which in turn encourage deep prejudices and notions of separatism. This is why Urania was so revolutionary for its time: its creators recognised the importance of deconstructing social categories that have been internalised as ‘natural. And sure, we might not agree that these binaries always cause problems, or that the creation of a society which is genderless for example is possible, it is nonetheless critical to recognise the importance of pulling apart these categories, so that we might rid ourselves of the deeply set social prejudices that arise from them.

What it comes down to is this: humans are remarkably diverse creatures, but are all too often divided into narrow ‘types’ that encourage the dominance of one group over the other. Urania drew attention to the flexible nature of these groupings – an extraordinary achievement in an age remarkably non-sceptical of ‘fixed’ social categories – and created an alternative way of thinking about the world.

So here’s to Urania, for opening the discussion; for questioning the previously unquestioned, and for being the gender rebels that we still so desperately need.

i) Urania, No. 69 and 70 (May – August 1928). p. 10

ii) Urania, No. 69 and 70 (May – August 1928). p. 10

iii) Urania, No. 69 and 70 (May – August 1928). p. 10

iv) Urania, No. 57 and 58 (May – August 1926). p. 10-11

v) Urania, No. 57 and 58 (May – August 1926). p. 2

vi) Urania, No. 69 and 70 (May – August 1928), p. 3

vii) Urania, No. 69 and 70 (May – August 1928), p. 4

—

Return to Early Lesbian and Gay Publications or the LGBTQ Collections Online Resource.

—