“It was my pulpit, with permission to make in it (what other pulpits lack so sadly!) such jokes as pleased me and to put forward on hundreds of matters my views of what was right and honourable.”

Frances Power Cobbe in her autobiography

In my last blog I gave an overview of Frances Power Cobbe and her work. My research has revealed a fascinating and extraordinary woman. As well as establishing a successful career as a journalist, I have found that her approach to journalism as a tool for social reform was entirely unique for a feminist at the time.

Bolshy, brazen, and strongminded, Frances was hell-bent in her defiance of societal expectations in Victorian Britain. Undaunted by what people thought a woman should be, she threw herself into the public world as a journalist. From refusing to wear a corset[1] to resolutely shrugging off the mantle of wife and mother, she flouted almost every social convention expected of her as a woman.

She was revered within the intellectual and feminist circles of the time.[2] Accounts of her that I have found by other feminists and notable woman tell of an extremely charismatic and funny person. Louisa May Alcott called her a ‘sunbeam’ who lit up any room and said that ‘It was truly delightful to see a woman so useful, happy, wise, and beloved.’[3]

However, it was outside these circles that she concentrated most of her work. She targeted wider Victorian society at large by writing for the mainstream press. The written press was central to Victorian culture,[4] much the same that social media and the internet is to us today. Frances established herself at the very centre of this. She strongly ‘believed in the power of the press’[5] and was unique, first, in that she wrote for this wide audience, and second, in that she made her work accessible to as much of Victorian society as possible.

She revelled in the freedom this afforded her as her autobiography records –

‘To be in touch with the most striking events of the whole world and enjoy the privilege of giving your opinion on them to 50,000 or 100,000 readers within a few hours, this struck me, when I first recognised that such was my business as a leader-writer, as something for which many prophets and preachers of old would have given a house full of silver and gold’[6]

Feminism took off in the second half of the 19th Century. With this came the advent of separate specialist feminist papers and journals. Feminists collaborated to create publications such as The Englishwoman’s Review and The Woman’s Gazette. These enabled the circulation of ideas, arguments, and vindications to subscribers and those sympathetic to the feminist movement. These women were adamant that a separate form of press was the best way to push for reform. Many feminists rejected the mainstream press, with those such as Bessie Raynor Parkes claiming that to write about feminism in mainstream publications would result in the “dilution” of its politics,[7] a watering down of the movement’s founding ideals in order to cater to wider society in which these views were generally given short shrift.

Despite this criticism, however, Frances forged ahead with a career as a feminist journalist within the established mainstream press, writing prolifically for publications such as Fraser’s Magazine and The Contemporary Review. As I said in my previous blog, she was one of the very few women to do so, and fewer still who wrote politically on women’s issues.

I believe that the value of Frances’ practice of journalism had an impact above and beyond that of the separate feminist publications. Without doubt, the specialised feminist publications were vital for the push towards social reform. Even so, I think it was mistaken to say feminist political arguments made outside of these publications were in some way weakened. Rather, they presented politics in a different way.

Writing for the mainstream was to write with a different purpose in mind. As Susan Hamilton says, the already established press provided ‘different podiums to mount.’[8] Frances used her writing skills to persuade those not yet bought into what Frances calls the “Woman Question,” rather than to preach to those already converted to the cause. She was inviting a much wider section of society, to read, consider, and engage with feminist arguments.

For me, this is what makes Frances’ journalism so outstanding. Through her work, she readily appealed to this wide audience, using lurid details of real-life stories of the various plights of individual women to coax her readers and appeal to public emotion and sentiment.[9]

In doing this, she made the Victorian population at large consider feminist issues, and in doing so was able to push for change. I can’t help but wonder if, without this, the feminist movement would have remained on the fringes of society, with ideas for reform being isolated within the echo chambers of a specialised feminist press.

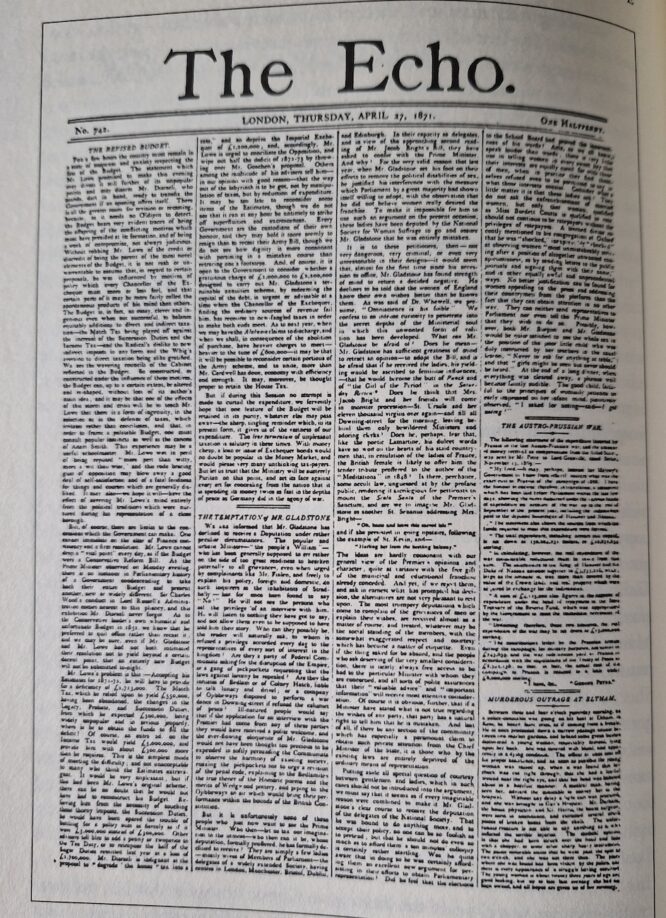

What makes Frances even more remarkable was that her work was not simply focussed within the mainstream press, but also spanned both intellectual journals and more low-brow, popular, and affordable papers. The daily paper, The Echo, was the first of its kind in that it was targeted more working- and middle-class readers by selling its daily issues for only a half-penny. Frances was one of the first to write for this paper as one of its leading journalists, making her arguments accessible to a much broader scope of the population.[10] She wrote prolifically for this paper for 7 years, publishing around 3 articles a week, which also brought an immediacy and urgency to the debate that the monthly or quarterly publications did not.[11] She used storytelling to bring a ‘texture’ to the debate that would grasp the public’s interest and sympathy.[12] She said of the paper that ‘our circulation, I believe, was very large indeed.’[13]

While the media was a fundamental part of the functioning of Victorian society, I can’t ignore the fact that there was a huge lack of equality of access, both in terms of poverty and education. Education especially wasn’t readily available to women – something that Frances spent a lot of her life trying to remedy. Although papers like the Echo were written with the working classes in mind, there would have been many who couldn’t read. And although the price of the Echo was intentionally kept low, there still would have been a significant part of the population who wouldn’t have been able to afford it. So, undoubtedly, the scope of her journalism did have limitations.

These societal constraints aside, it can’t be denied that by writing for the more working and middle classes in mind, Frances was able to disseminate her ideas and arguments to as many people as possible, engaging more people than ever, inviting them into the political conversation on feminism. In doing so, she broadened the “Woman Question” throughout Victorian culture. At a time when more and more men were being given the vote, this was crucial for pressuring Parliament to enact social reform.

And so, by detaching herself from the more niche feminist publications and publishing her work predominantly in the mainstream press, she expanded both her audience and the accessibility of her writing, making feminism one of the central debates of the Victorian era. I think this is what made Frances so unique and influential. These efforts should be recognised and applauded today.

[1] Lori Williamson, Power & Protest, Frances Power Cobbe and Victorian Society, Rivers Oram Press, 2005, p.91-2

[2] Lori Williamson, p.91

[3] Louisa May Alcott, ‘Glimpses of Eminent Persons,’ The Independent, 1 November 1866

[4] Susan Hamilton Ed., ‘Criminals, Idiots, Women & Minors’ Nineteenth-Century By Women on Women, Broadview Press, 1995, p.9

[5] Susan Hamilton, Frances Power Cobbe and Victorian Feminism, 2006, p.1

[6] Frances Power Cobbe, Life of Frances Power Cobbe, 1894, p.390

[7] Susan Hamilton, 2006, p.9

[8] Susan Hamilton, 2006, p.15

[9] Susan Hamilton, 2006, p.108-111

[10] Sally Mitchell, Frances Power Cobbe, Victorian Feminist, Journalist, Reformer, 2004, University of Virginia Press, p.186-187

[11] Frances Power Cobbe, p.391-392

[12] Susan Hamilton, 2006, p.106

[13] Frances Power Cobbe, p.391