Normally in writing a piece like this, you want to hook the reader with the first paragraph, give them a story to latch onto before you dive deeper. But, because this is cricket – a sport whose language is as opaque as the grey clouds that get matches cancelled – I realised that opener might be as likely to put some of you off as it was to draw you in.

If the only words that make sense in my original opening are ‘Abu Dhabi’, ‘World Cup’ and ‘Edinburgh’, don’t worry. The history we’re about to explore doesn’t require you to know how many balls are in an over or what a leg-bye is. It does, though, set the stage for a recent first in Scottish women’s cricket, before I take you back 90 years to a different one entirely:

In early May this year, in weather warmer than both teams are used to at home, Ireland and Scotland took to the field in Abu Dhabi. At stake was a place in the upcoming T20 Cricket World Cup. The match that day can be read as a story of two women from Edinburgh: captain Kathryn Bryce and her sister Sarah, Scotland’s wicketkeeper. Ireland’s batters went first with Kathryn’s bowling taking 4 of them out. Sarah had a hand in sending another two back to the dressing room. Ireland slogged on, putting on a middling but not atrocious number of runs. When Scotland batted, they needed a total of 111 runs to win. By the time Sarah joined Kathryn with her bat, they needed just 13 more to qualify for their first major tournament. Kathryn hit the final ball of the game for 4 securing – for the very first time – Scotland’s place on the world stage of cricket.

These are not the women we’re going to focus on though. Instead, we’re going back to October 1934 when 15 women set off on a month-long boat journey to Australia to play cricket. They were the first England women’s cricket team. In the line up, though, were several Scottish women. But they wouldn’t have been there – and, I’d argue, there might not have even been a team at all – if it wasn’t for the suffrage movement.

The first thing you learn when you start looking at suffragettes and suffragists is that they didn’t stop with the Representation of the People Act. What I mean is that they’d got the vote, sure, but they didn’t just down tools and go back to quiet little lives. Many of them continued to be activists in ways that mattered to them, campaigning for workers rights, animal rights or even fascism. And some of them turned their attention to women’s education.

As a profession, teaching was one of only a handful considered respectable for women. There were a lot of teachers involved in suffrage and some of them specialised in Physical Education. In Scotland, Dunfermline College became the place where female PE teachers trained. Two of its first three headmistresses – Ethel Adair and Mary Tait – were openly involved in the suffrage movement. So many of the women being taught PE in the interwar years were taught either by women involved in suffrage or women trained by suffragists. This boom in specialist PE teachers led to more girls than ever getting involved in sport.

One place where suffrage directly interacts with the 1934 team is at St Leonards School in St Andrews. The school for girls was modelled on many of the all male public schools in England, which meant that sport was central to its curriculum – including cricket. In 1932, a match between England and Scotland was organised, with most of the Scotland team coming from St Leonards. Suffragist Louisa Lumsden was the school’s first headmistress and is best known in Glasgow as the woman who planted the Suffrage Oak in Kelvingrove Park in 1918, after the vote had been won for (some) women.

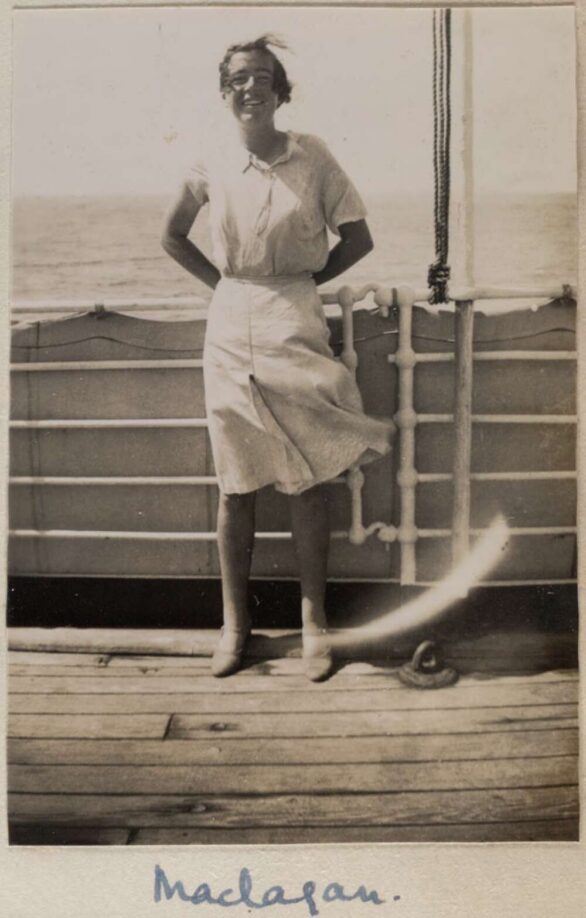

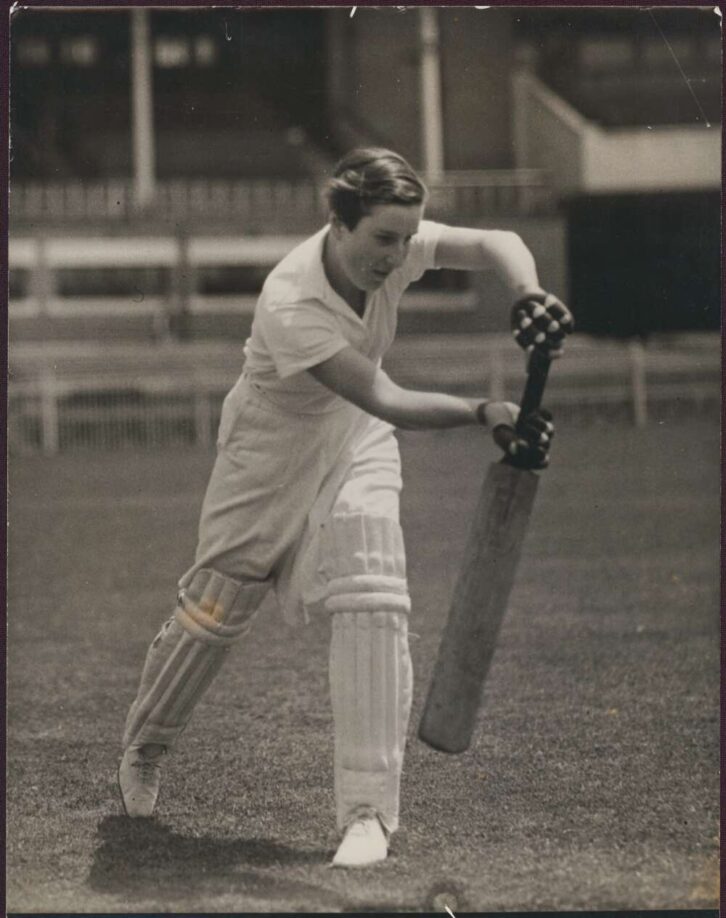

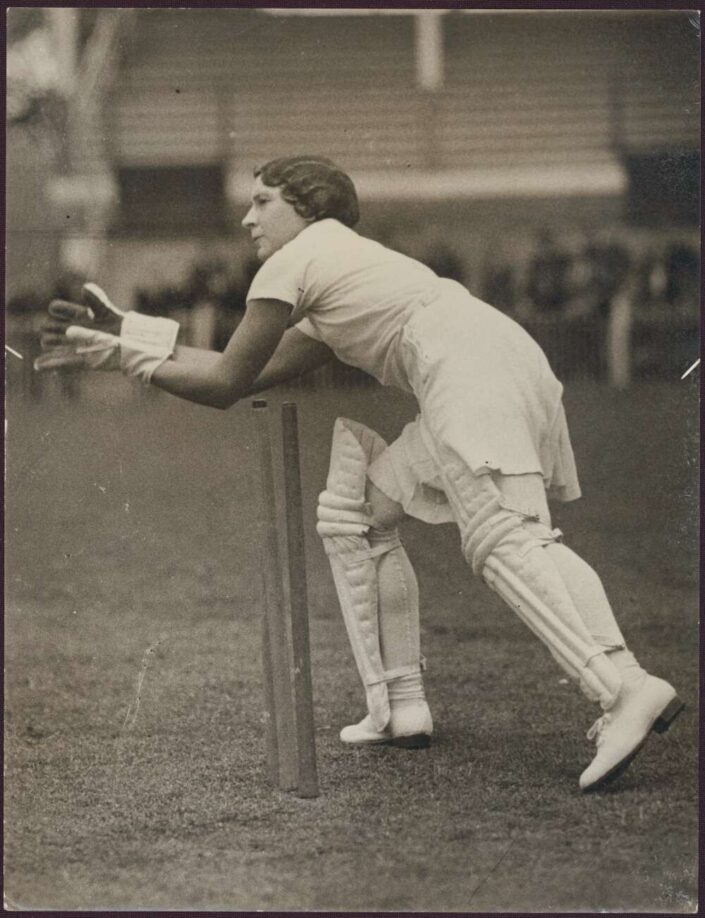

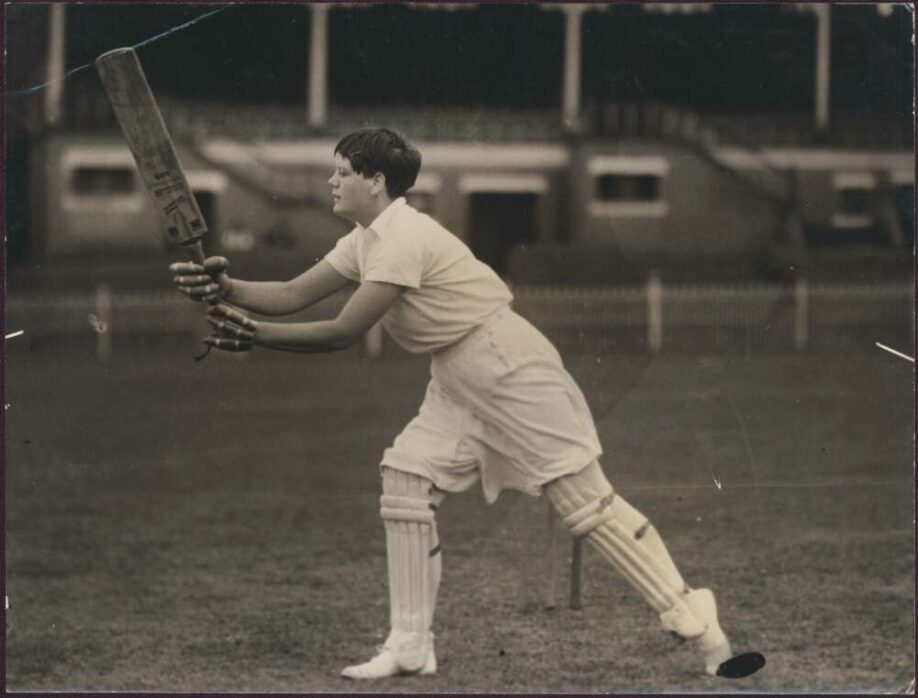

Four of the Scotland team from 1932 sailed to Australia to play for England in 1934. They were also probably some of the most valuable players in the team: opening batter Myrtle Maclagan, wicketkeeper Betty Snowball, the youngest player Joy Liebert, and captain Betty Archdale. The two Bettys – Snowball and Archdale – had both been students at St Leonards, where they played cricket.

It’s through Betty Archdale that we come to the last suffragette in our story: her mother, Helen Archdale. Helen also went to St Leonards and joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, quickly becoming involved with its leadership. When Betty was only 2, Helen went on hunger strike with Maud Joachim and other suffragettes after being arrested in Dundee for disrupting Winston Churchill’s speech. The women were awarded the Hunger Strike Medal for their action and GWL now holds Maud’s medal.

Betty remembered visiting her mother in Holloway gaol following a different arrest; one prominent suffragette was her godmother, another was her governess. To me, it feels obvious that a woman who’d grown up around these women – women who set out to change the world when much of it was telling them they couldn’t – would think nothing of leading another group of women in breaking a different boundary. Or just hitting it over the boundary.

Although her biography is called The Suffragette’s Daughter, Betty was very much her own woman. She qualified as a barrister in London before moving to Australia and becoming a radical voice in women’s education. Before she died in 2000, she’d been named one of 100 Australian Living National Treasures and was one of the first 10 women given membership to the notoriously all male MCC in London.

I talked about Kathryn and Sarah Bryce in my opening but special mention in that match should also go to Glasgow’s own Abtaha Maqsood, who caught two and bowled a third out. She’s the first professional cricketer in Britain to wear the hijab, was a flag bearer at the 2014 Commonwealth games in Glasgow, was training to be a dentist (she’s paused this to pursue cricket for now), and has read two bedtime stories for Ceebies. That summary alone doesn’t do her justice but the thing about her that stands out for me is both how exceptional and how unexceptional she is. The history of women’s sports is filled with remarkable women like Abataha and women like Betty: women who are phenomenal at their sport but also have entire other extraordinary careers and achievements outside it as well. That was as true of the England women of 1934 as it is today.

Scotland play hosts Bangladesh at 11am BST on 3rd October 2024 in the opening game of the Women’s T20 World Cup.

Atkinson, Diane. Rise up, Women! The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes. Bloomsbury, 2018.

‘Betty Archdale’. The Guardian, 16 Feb. 2000. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2000/feb/16/guardianobituaries3.

‘Betty Snowball Profile – Cricket Player England | Stats, Records, Video’. ESPNcricinfo, https://www.espncricinfo.com/cricketers/betty-snowball-53729. Accessed 7 Mar. 2024.

Duncan, Isabel. A History of Women’s Cricket. Robson Press, 2013.

England Women v Scotland Women in 1932. https://cricketarchive.com/Archive/Scorecards/333/333492.html. Accessed 20 Sept. 2024.

Flint, Rachael Heyhoe, and Netta Rheinberg. Fair Play: The Story of Women’s Cricket. Angus and Robertson, 1976.

‘IRE-W vs SCO-W Cricket Scorecard, 1st Semi-Final at Abu Dhabi, May 05, 2024’. ESPNcricinfo, https://www.espncricinfo.com/series/icc-women-s-t20-world-cup-qualifier-2024-1425615/ireland-women-vs-scotland-women-1st-semi-final-1425658/full-scorecard. Accessed 23 Sept. 2024.

‘Joy Liebert Profile – Cricket Player England | Stats, Records, Video’. ESPNcricinfo, https://www.espncricinfo.com/cricketers/joy-liebert-53798. Accessed 23 Sept. 2024.

Kay, Joyce. ‘It Wasn’t Just Emily Davison! Sport, Suffrage and Society in Edwardian Britain’. The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 25, no. 10, Sept. 2008, pp. 1338–54. Semantic Scholar, https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360802212271.

—. ‘“No Time for Recreations till the Vote Is Won”? Suffrage Activists and Leisure in Edwardian Britain’. Women’s History Review, vol. 16, no. 4, Sept. 2007, pp. 535–53. Semantic Scholar, https://doi.org/10.1080/09612020701445909.

‘No Smoking, Drinking, Gambling … or Men’. ESPNcricinfo, https://www.espncricinfo.com/story/no-smoking-drinking-gambling-or-men-331397. Accessed 7 Mar. 2024.

Salmon, Carol. Snowball, Elizabeth Alexandra [Betty] (1908–1988), Cricketer. Oxford University Press, 2004. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/64957.