Making a jumper for someone else is an intimate act. Even setting aside the cost and time, you’re making thousands of tiny stitches by hand that will lie across its wearers shoulders, wrap around their body and hug their figure. To make a jumper for yourself is to turn all that intimacy onto your own body and sheathe it in your own decisions.

Decision number one: what do I want it to look like? It’s one of the great freedoms that come from making your own clothes, you get to make exactly what you want to wear, not what a fashion buyer thinks you’ll want to wear when you’re in the shops. The Woman’s Woolly comes with two versions, the one I’ve already made and a “pullover”, the same jumper but made sleeveless. I’m not short on jumpers but I haven’t made a sleeveless one in a while and something about its slouchy shape appeals to me.

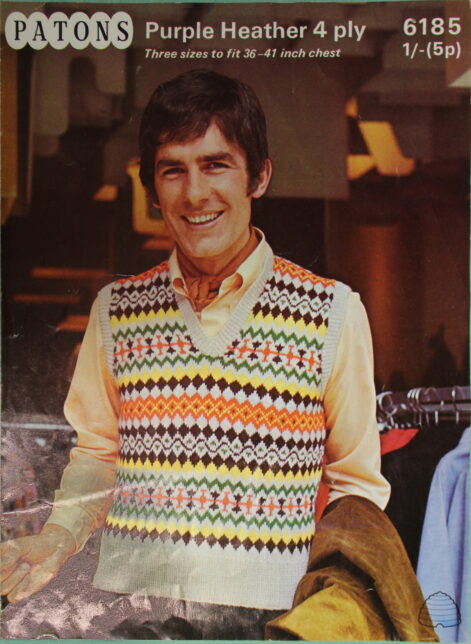

Sleeveless jumpers turn up about every 20 years with a startling regularity. In the GWL archives we have examples from the 1920s with a very fashionable deep neck and dropped waist. In the 40s, wartime rationing limited the amount of wool available making sleeveless jumpers popular and patterns often incorporated Fair Isle motifs to use up valuable scraps of yarn. The 70s jumpers are deliberately referencing back to those ‘simpler’ times of their parents but often using brighter colours and patterns in line with the Peacock Revolution. The most famous sleeveless jumpers of the 90s were seen in the movie Clueless, figure hugging and machine knitted, evoking a particular American Ivy aesthetic.

The current crop of sleeveless jumpers turned up on runways in about 20161 and – as with all things high fashion – have slowly made their way into the mainstream. In the last 3 years, there’s been no end of articles on how to style a sleeveless jumper. Most noticeably different from previous incarnations is the square shoulder: instead of following the line of a shirt seam, it instead stops part way down the upper arm, creating a more relaxed, punk look. It’s exactly the way the Spare Rib pullover is constructed: our 1980s jumper is on trend for the 2020s.

With that settled on, I then get to pick what colours I want for my jumper. This one needs to be me and I’m not really a navy and grey kind of woman. In fact, nobody who has ever met me would describe me as ‘quiet’. These days my style reflects that so I go hunting for a yarn that’s as loud as I am. I settle on West Yorkshire Spinners ColourLab DK (another of my favourite workhorse yarns) in Cerise Pink, .

My teenage self would be appalled that I chose pink – she grudgingly accepted her womanhood and fiercely rejected any connection between softness and femininity. A girlhood spent in boys clothes, avoiding the colour of Barbie and ballet, grew into an adolescence wrapped in black velvet, accented with red and purple. Both periods were constrained by strict rules: a way to place limits on the infinite possibilities of this vast thing called fashion but also to forcibly expand the boundaries of this thing called ‘girl’. If I had to be one, I would not be pink, I would not be sweet, I would be more.

So why, then, would I make this jumper in pink? The facetious answer would be ‘because I want to’. The honest answer is that the girl who spent so much time not being like other girls, grew into a woman who realised there was nothing wrong with other women. Vilainising femininity and its trimmings as weak hadn’t made me strong. It wasn’t its softness that held women back but the degradation of that softness.

When I read Eleanor Medhurst’s post on the relationship between lesbians and pink, the first thing that came to mind was Dolly Parton. (Stay with me, I am going somewhere with this.) Medhurst argues that by choosing to wear pink – including in a purposefully exaggerated way – lesbians undermine the heterosexist femininity typically associated with the colour. Which is where Dolly comes in: “Find out who you are and do it on purpose.” By doing pink “on purpose”, we rob it of its constrictions; it can’t be sweet and delicate and straight on a body that doesn’t conform to those things either. As Medhurst puts it, wearing pink “has the potential to recreate the meaning of a symbol that has been used to oppress us.”2

I could go into the history of pink as a colour in fashion, its shifting relationship to gender and its reclamation by queers and punks, but this is already long enough and not actually relevant to my choice to knit a pink jumper. Its historical position is interesting and undeniably important in its own right. However, I’m not creating a piece of history: I’m creating a current piece that I’m going to wear. My relationship to the jumper (and, to a lesser extent the reaction of the audience who sees it) and to the colour has more relevance here than pink in a historical context.

Being purposeful in my clothing choices and what they might say has become an important part of my philosophy of dressing. As I’ve gotten older, like many women, I’ve begun to care less about what other people think about what I wear. Whereas for many women that means wearing what they like because it’s comfy or practical and liberating themselves from fickle trends (which is valid even if, as I established in Part 1, it doesn’t totally mean they’ve opted out of fashion). For me, clothes have become play and, with it, so has femininity. It can be hard – sharp lines, crisp darts, carnal colours – and masculinity can be soft. And I can pick them up and put them down at my whim. My clothes can be referential: a pinstripe button down shirt shouts 80s capitalist greed, all aggressive machismo. My clothes can subvert: that same shirt unbuttoned to my sternum, with a lace vest peeking out from beneath and worn jeans blurs away that formality and machismo into something else. My clothes can be anything I want: a semiotics of stitches for anyone ready to read them.

So not only is this jumper deliberately pink, I want it to be symbolically loud in other ways. The feminism of the late 70s and early 80s could be a little one note – focused on the needs of white women, often from middle-class backgrounds. Modern feminism – my feminism – is intersectional. (Or at least it aspires to be.) It recognises the complexities of women’s lives and how other aspects of women’s identities impact on them. It also acknowledges that ‘woman’ isn’t necessarily a binary concept.

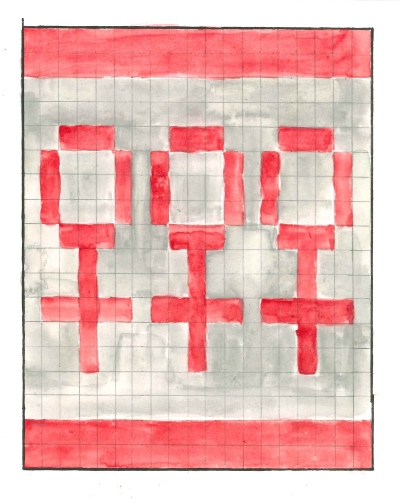

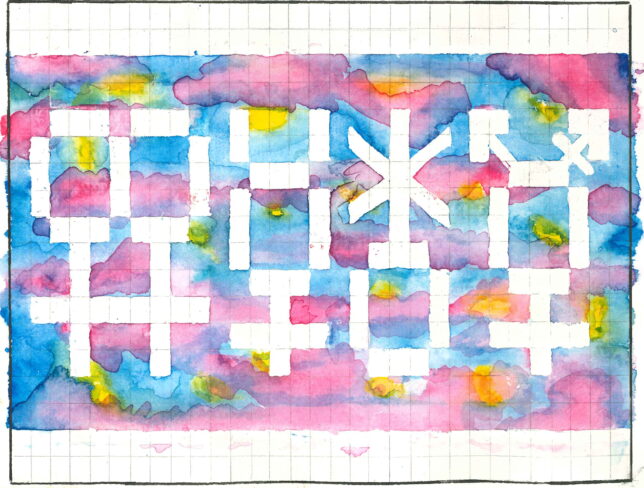

And all of that is a lot to ask of a jumper. It’s a lot to express in words, never mind yarn. But taking that concept of the ‘one note’, I begin to adapt the Venus symbol into a symphony of gender. Each is a 6 stitch repeat so I start with one of the oldest symbols, the interlocking Venuses to symbolise lesbians. Then I create the combined Mars and Venus symbols of the trans symbol. My last two are symbols for non-binary and intersex people (although the Mercury symbol has been used to symbolise certain nonbinary genders too so it’s doing double duty here). I’m not removing the Venus – it’s still the major motif of the jumper – I’m just augmenting what’s already there with our greater understanding of gender. There will be 25 Venuses on the jumper and 4 new symbols when it’s finished. I test them with some scrap yarn. The double Venus and the Mercury symbol knit up perfectly but the trans symbol and the other non-binary one look too crowded. I decide to knit parts of the symbols but I’ll go in afterwards and sew the details on.

I know what’s going on the band but, at this point, I don’t know what the band is going to look like. The pink is settled but the yarn for the rest of it is yet to be determined. What I do know however is that I want it to reflect another modern shift in knitting: the indie dyer. I’m going to come back to this in more detail in Part 4 because it’s directly related to other changes in the culture of knitting but what you need to know is that there is an entire industry of (mostly) women hand-dying individual skeins of yarn in interesting colours all over the world. If you can picture a colour combination, someone has probably dyed it.

As well as selling online, indie dyers also come together at yarn festivals where (mostly) women congregate to buy yarn, show off their proudest creations and talk about having “spent far too much” on indie yarn. (The amount of times I’ve heard this phrase is unreal. Do men have this level of guilt about their hobbies?) Glasgow’s local festival is Glasgow School of Yarn. I’d planned on attending the 2023 event anyway but decide it’s my best chance to find something for the project.

Glasgow School of Yarn is held in the Georgian splendour of the Trades Hall. It’s the home to Trades House, the umbrella organisation established in the 16th century to represent the skilled craftsmen of Glasgow. And I use the term ‘craftsmen’ deliberately. The youngest of the crafts is the Bonnetmakers & Dyers who, along with bonnets, was responsible for knitted stockings, underwear, and similar wool garments. And although women have always been a part of textile industries, the Bonnetmakers & Dyers didn’t officially admit their first female member until 2003.3 It’s not lost on me that the women filling this space and keeping its craft and traditions alive are the same ones it spent centuries excluding.

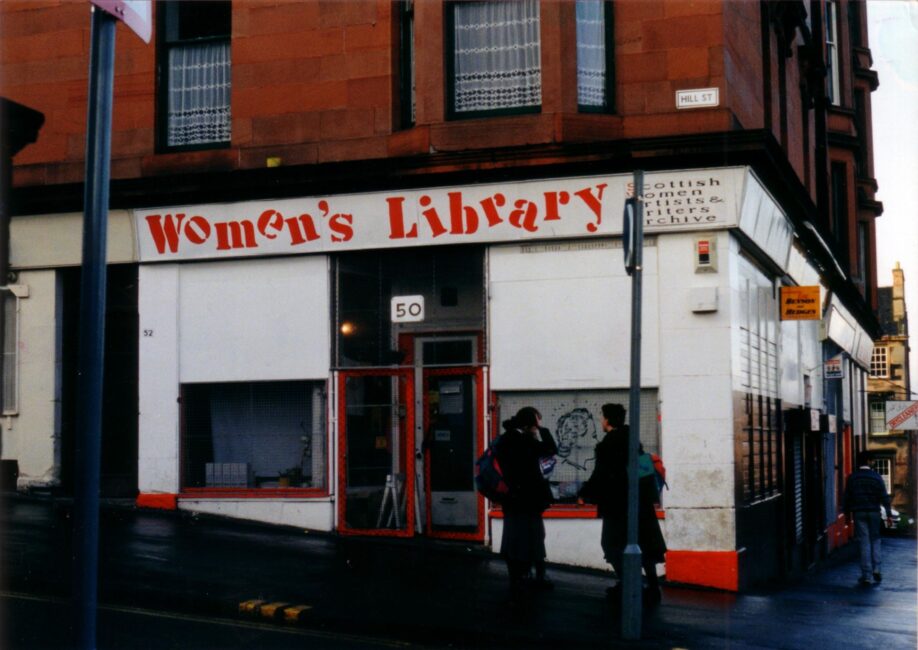

Stall after stall bejewelled in kaleidoscopic yarns fills panelled room after panelled room. Wearing my newly finished Victorian jumper (I told you I’ve knit a few historical patterns), I make a beeline for the stall of For the Love of Yarn, a dyer whose studio is based a few streets from GWL in Bridgeton. The idea of knitting this with yarn dyed so close to the Library is just too wonderful a chance to pass up. I explain the project to her and she helps me pick out a skein of her DK. After weighing a few options, I settle on ‘Royal Flush’, a beautiful set of blues and pinks with splashes of yellow and purple. Something about it reminds me of different pride flags and, when paired with the cerise, the contrast is delicious.

For my third colour I decide on white. This isn’t for any ideological or symbolic reason: I just finished knitting a baby blanket and have some left over. It’s not as strong of a contrast as between the grey and burgundy but I like it. And it’s not like the jumper needs to be any louder at this point.

Like with the original Spare Rib jumper, even before I’ve started to knit, this jumper is telling a story. Except this time, it’s my story. My story, my politics, my performance of gender, my body, my creativity. It’s deeply personal but simultaneously deliberately connected to other ideas outwith just my self. And somehow that feels even more in the spirit of the original jumper than the 80s replica now in the GWL collection.

So I suppose I better get on and knit it. That’s Part 4.

- ‘Take It From This Saint Laurent Model: Nobody Is Too Cool for a Sweater-Vest’. Vogue, 14 Jan. 2016, https://www.vogue.com/article/sweater-vests-cool-again-saint-laurent-model-approved. ↩︎

- Medhurst, Eleanor. ‘Subverting Pink’. Dressing Dykes, https://dressingdykes.com/2020/08/21/subverting-pink/. ↩︎

- Bryce, Craig. Lady Burgesses and Guild Sisters. Trades House of Glasgow, Jan. 2019, https://www.tradeshouselibrary.org/uploads/4/7/7/2/47723681/female_members_of_the_trades.pdf. ↩︎