The launch of our Summer programme brings with it the start of our literary festival Open the Door 2023 – a bold, ambitious celebration of women’s writing, reading and creativity, brimful of convivial conversations, fresh perspectives and outstanding talent. Each year OTD has a theme – and this year it’s Writers/Activists. In this blog our volunteer Ashley talks about one of her favourite writer/activists, Ursula LeGuin.

Read more about Open the Door and sign up to some events here!

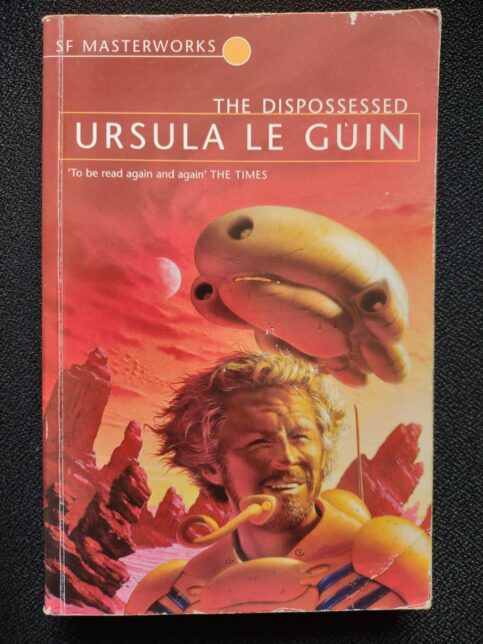

I first encountered the writer Ursula Le Guin in my second year of my undergraduate degree, where one of the set texts we were to read was The Dispossessed (originally published in 1974). The novel follows an intelligent physicist called Shevek who discovers a mathematical equation which will enable faster than light communication and – potentially – travel. He lives on a moon called Anarres, where everyone lives in an anarcho-syndicate system; there is no centralised government, and (almost) everyone prioritises the betterment of society in their harsh, semi-barren world which forces them to work together. Anarres co-orbits a moon called Urras and, having won an award there, Shevek travels to the other moon even though it incurs the anger of many of his fellow Anarrens, whose ancestors had escaped religious and political persecution around 200 years before. He hopes that those on Urras will see his formula as he does: a chance for bettering the lives of both those on Urras and Anarres. However, the world he encounters is a capitalist, divisive and sexist world (sound familiar?), where he is exploited by those in power in an attempt to keep the formula for themselves. Realising his mistake, and almost being held captive, Shevek ends up escaping back home to Anarres, to an unknown fate.

This is a very condensed summary of one of the most complicated novels I’ve ever read, but I hope it paints a relatively clear picture of how much a political commentary this novel is. Le Guin wrote that the novel was born out of a desire to depict an ‘anarchist utopia’ and was in direct opposition to the approach taken during the war in Vietnam. Although Anarres isn’t perfect, and has corruption if you know where to look, it does represent a vision for a system where no one person or party is in charge, and where – overall – everyone works together to raise their children, grow food, deal with natural disasters, and survive together. After all, absolute power corrupts absolutely. This novel is a fantastic development of that idea – what if there was a society where there was no absolute power?

Urras is used to contrast Anarres and to draw comparisons with our society too. Although Le Guin wrote this in the 70s, there are so many parallels with how we operate today, particularly with the cost-of-living crisis and the rampant exploitation of the poorer levels of society, which are the result of large corporations attempting to keep profit margins up in uncertain conditions. The war in Ukraine bears striking resemblance to the main war in the novel, where the A-Io state on Urras declares war on a third country in order to gain more power over their rivals. The idea of different states each pursuing their own agenda, at the cost of cohesion and global unity is, again, a familiar reality. Finally, the relentless pursuit of profit and individualism in the face of environmental destruction is a painful reminder of our current global crisis.

This is not to say the novel is depressing. Far from it. If you asked me what book had the most impact on the way I think, this would be it. And I’ve only read it once (shame on me). Instead, the beauty of Le Guin’s writing is that instead of shaming the reader into feeling guilty about not being an activist and taking on the world’s problems, she lifts the reader up to think about the ‘bigger picture’ issues in an enlightened and engaged way. She inspires the reader to actually think about how and why systems work in the way they do. She gently calls you to action, as opposed to Marx’s more demanding ‘workers unite!’.

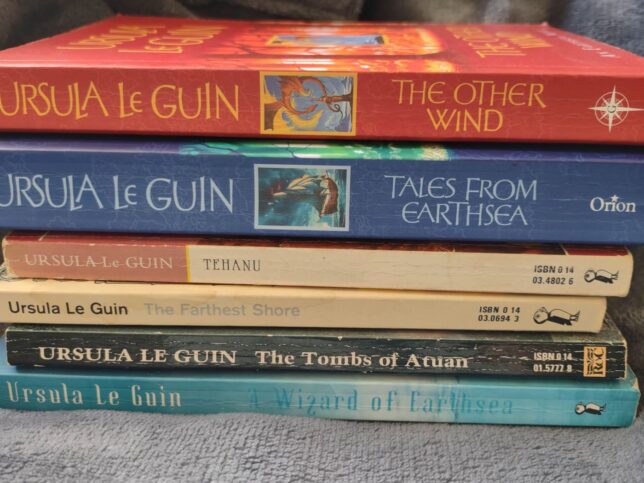

I would argue that Le Guin’s writing is fundamentally an act of activism. Every single piece of her work that I have read pushes you to reimagine boundaries, challenge the status quo, and encourages radical thought in a world that wants you to conform. Le Guin’s Earthsea Cycle – which is her main fantasy work – is a beautifully written saga, which, although far less overtly political than The Dispossessed, also prompts the reader to question society around them, from how gender is constructed to how members of different races relate to each other. By using different point-of-view characters, and utilising the analogous power of fantasy, Le Guin interrogates the fundamental interactions that take place both between people and inside individuals (such as crises of confidence or an individual becoming more socially aware).

Most radically, in her essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ (which I would highly recommend reading), Le Guin argues that the way in which we tell stories is fundamentally wrong. She notes the importance of storytelling to humans, as stories have the power to demonstrate relatability between us and to convey deep, powerful meaning. She then goes on to humorously argue that we have ruined stories, by letting the Hero run amok and take over everything, and having conflict at the heart of every story we tell. Pointing out the shape of narratives, she writes,

So the Hero has decreed through his mouthpieces the Lawgivers, first, that the proper shape of the narrative is that of the arrow or spear, starting here and going straight there and THOK! hitting its mark (which drops dead); second, that the central concern of narrative, including the novel, is conflict; and third, that the story isn’t any good if he isn’t in it.

Instead, she advocates for thinking of stories as bags: holding words and meaning. She urges us to consider stories – novels especially – as ‘a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.’ Of course, conflict will naturally occur, but making it the focus doesn’t work in her view. And the Hero? Well he doesn’t belong in the bag; relatable, messy people do. Stories should be used to help us connect to each other and – through the view of other worlds or situations – to help us see our own reality for what it is. She concludes,

all serious fiction, however funny, is a way of trying to describe what is in fact going on, what people actually do and feel, how people relate to everything else in this vast sack, this belly of the universe, this womb of things to be and tomb of things that were, this unending story.

I find a lot of comfort in her words. I also find a lot of comfort in her novels because I feel like the world, as messed up as it is, is being critiqued in a serious way by someone. I feel that my own struggles are valid and relatable. That there will be a time where I’m called to action but when it does happen, I’ll be ready. I have a lot of love and admiration for Le Guin and her writing as she has pushed me – gently but firmly – to be a more socially-conscious and engaged person. Give The Dispossessed a go and see what happens.

You can find The Dispossessed on the shelves of our amazing lending library at GWL!

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.