Part 3: Is Fact-Twisting a Bad Thing?

Hello, avid reader, and welcome back to this final instalment of my blog series on Historical Fiction!

It’s been a few weeks since my last entry, so here’s a little refresher to kickstart your memory: in my last entry on the topic I discussed the difference between accuracy – the extent to which a work of historical fiction sticks to known historical facts – and authenticity – the extent to which the respective novel’s depiction of the past ‘feels’ real. I pointed out that the latter tends to be highly subjective and that, while the two concepts often go hand in hand, the depictions of historical novels can be factually inaccurate yet convey the past in a way that feels authentic to the reader. I ended by asking if you could think of a reason why this might be problematic, at times. What happens when an author decides to stray from commonly accepted historical narratives? Why do they do it? And what are the possible downsides to such choices, and what can be positive about them?

Why Change the Facts?

The first important keyword we should bear in mind is “accessibility” as one of the most obvious and easy explanations for deviations from generally acknowledged truths about history. Put simply, a work of historical fiction always needs to be accessible or understandable to a modern audience, no matter where or when it is set. As The Guardian’s James Forrester puts it:

“One cannot have medieval characters using correct period language because no one would find the speech readable. Similarly, an accurate portrayal of a world in which most dutiful and conscientious fathers will regularly beat their sons is likely to alienate readers.”

Sometimes, we don’t even know how people might have articulated themselves or much less how they would have pronounced words back in the day – and even if we do, actual recreations of such language use would most likely make for a very tedious and exhausting reading or viewing experience. Similarly, the depiction of aspects of every-day reality which were completely normal during the times depicted, yet which modern audiences would find questionable or would even be repelled by, could negatively influence their ability (or willingness) to empathise with the characters. Accordingly, such things are often left out so as not to distract from, or get in the way of, the story’s main focus. Since these aspects are often seen as fairly inconsequential, however, audiences and critics are usually quite lenient when it comes to the common practice of leaving them out, as long as the depiction of the main events stays as close to what is generally accepted as the truth as possible.

However, what happens when authors decide to make more drastic changes? A possible problem arising from such inaccurate depictions results from the possibility of people not questioning what they read or watch. Particularly when it comes to niche topics, a historical novel on the subject may be the only account of these events that many people will ever come into contact with, so that inaccurate depictions may lead to miseducation and misconceptions, especially when a novel was written with an ideological agenda in mind. No doubt, an account of WWII written by a supporter of a fascist party would be very likely to distort events and might prove to be dangerous for an uninformed or easily impressionable mind. This is, of course, an extreme example: the deviations or ideological touches may be smaller or much more inconspicuous, almost unnoticeable even, for example when the author downplays the role a particular person played in historical events or exaggerates them.

Absence through Presence: “Unwhitewashing” History

Another issue, and a highly disputed one at that, relating to the question of the down- and upsides to factual inaccuracy in historical fiction revolves around what is sometimes called the “unwhitewashing” of history or, in the case of movies and television shows, “colour-blind casting” – the hiring of actors for roles in traditionally ‘white’ genres irrespective of ethnic background or skin colour. Let me give you two examples:

First, there’s Netflix’s 2021 show The Irregulars, which revolves around a group of teenaged misfits investigating a series of apparently supernatural crimes for Dr Watson and Sherlock Holmes. Its main protagonist Bea, played by Chinese-born Irish actress Thaddea Graham, was clearly meant to strike a chord with a modern female audience craving strong and independent female leads: throughout the show, we can see her solve crimes, behave cheekily and rudely towards people above her station without there being any consequences for her actions, and boss around (old white) men – a fact that none of them seem to have any problem with. In short, neither racism nor her gender are ever an issue within the show, which is an undeniable historical inaccuracy. Even nowadays, a teenage girl shouting orders would not be readily accepted by many people; however, she definitely would have encountered a lot less openness to being ordered around among men in late nineteenth-century patriarchal England – which is something that many reviewers have pointed out.

A similar discussion arose around the popular Netflix show Bridgerton: the concept of ‘colour-blind casting’ usually comes up in these debates yet has been strongly opposed by the show’s creators and fans when talking about the choice to cast actors from minority ethnic backgrounds for the roles of nineteenth-century English aristocrats. For example, Kathryn Drysdale, who plays the series’ dressmaker Genevieve Delacroix, suggests the term “colour-conscious casting” as a much more appropriate description – conscious both of the factual reality of the past and of the needs and demands of the present. As she puts it: “[The show’s production company] Shondaland thinks that it’s very important that people see themselves reflected on screen […] I think that’s how you truly connect to your audience and those stories.” (BBC Scotland).

She argues that people watching the show will undoubtedly be aware of the fact that the historical realities would not have allowed some of the actors to occupy the position in society that their characters do – and that is exactly the point: through this obvious discrepancy between what the audience can see on screen, and what they know to have been factually true, such “colour-conscious” casting can draw attention to the discrimination of the times and the ‘whiteness’ and historical lack of diversity in higher social ranks of society. Paradoxically, the factual inaccuracy inherent in this depiction thus manages to ram home the reality of historical truth. In such cases, the creators making use of their artistic liberty is clearly a positive and meaningful contribution: they are not blind to historical reality; rather, they are highly conscious of it and decided to stray from historical accuracy for the sake of making a point, and a good one at that. Absence is highlighted through presence, and in a way that is much more blunt and obvious than many historically accurate depictions of past times, especially when it comes to a white audience. After all, issues of racism probably won’t be at the fore of many a viewer’s mind when they are watching one of the many all-white Jane Austen or Shakespeare adaptations. They will be, however, when watching Bridgerton, which, I think, is proof of the success of the show’s strategy.

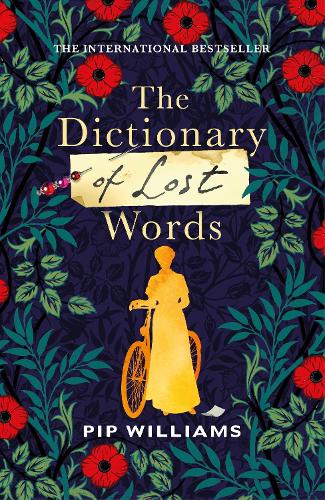

The Dictionary of Lost Words and Forgotten Women

The final work of historical fiction that I would like to talk about in this context (and in this blog series in general) is Pip Williams’s The Dictionary of Lost Words. This wonderful novel brings to life the history of the first Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and revolves around the fictional character of young Esme who, after the death of her mother, spends most of her childhood in the so-called “Scriptorium”, a garden shed in Oxford where her father and a team of lexicographers are compiling the first OED. From her favourite spot under one of the tables, Esme starts collecting those words that are discarded or neglected by the men and, as she gradually realises that some words are regarded as more important than others, she decides to create her own dictionary: The Dictionary of Lost Words.

Historically, the compilation of the first OED is generally attributed to men, and especially to James A. H. Murray and his male colleagues. However, there were also numerous women involved who made significant contributions. According to Pip Williams, “[t]here were women assistants. There were women volunteers, but we don’t know much about them.” During her research, the writer was increasingly frustrated by the fact that these women’s work has been lost to history – that they never received any credit or recognition for their dedication. One specific event in the genesis of the OED particularly enraged her in this context: in 1928, the completion of all sections of the dictionary was celebrated at a dinner in London’s Goldsmith Hall. 150 men attended – among them high-ranking guests like Stanley Baldwin, who was prime minister at the time – yet none of the women who had been involved had been deemed worthy of a proper invite. You might be wondering about the little word “proper” in the previous sentence now. Well, you see, the thing is: three of the women the work of whom had proven invaluable to the compilation – Edit Thompson, Rosfrith Murray and Eleanor Bradley – had indeed been invited. Oh yes, they were given the great honour of sitting outside on the balcony and watching the men stuff their faces and give themselves a pat on the back for a job well done. Isn’t that just peachy?

Unsurprisingly, Pip Williams wasn’t all that happy about the lack of recognition these women had received, which is why she made it her mission to find out more about their contributions to the creation of one of the world’s most famous dictionaries – a task, however, which turned out to be quite difficult. On Lithub, the author writes:

“It took me a while to find the women, and when I did, they were cast in minor and supporting roles. There was Ada Murray, who raised 11 children and ran a household at the same time as supporting her husband in his role as editor. There were Edith Thompson and her sister Elizabeth, who volunteered for the Oxford English Dictionary from the publication of the first words in 1884 to the publication of the last in 1928. There were Hilda, Elsie and Rosfrith Murray, who all worked in the Scriptorium to support their father. And there were women whose poetry and prose were considered evidence for the meaning of one word or another. But in all cases, these women were outnumbered by their male counterparts, and history struggles to recall them.” (Lithub, April 2021)

Women and Representation in the first OED

The more Williams kept thinking about the lack of representation of women in the history of the dictionary’s creation, the more she started wondering about the representation of women and their experiences in the dictionary itself. How were women and ‘typically female’ experiences in life, as well as the words expressing those, represented in this first edition of the OED? More and more, she came to realise that words from stereotypically female spheres of society were oftentimes not captured in writing and were thus discarded by, or remained unknown to, the men compiling the dictionary: for example, the word “bondmaid”, which denotes a young woman who was bound to servitude until her death, never made it into the first edition of the dictionary. Despite the fact that, like many similar words, “bondmaid” was suggested by a member of the public – note that such public suggestions for words were an important part of the dictionary’s compilation process – the little piece of paper with the word’s definition is still missing from the archives today.

“And so I have put a girl called Esme under the sorting table of the Scriptorium”, Williams says, “where all the words of the English language are being defined. I have made her steal that lost word, bondmaid, and then I’ve imagined the influence this word might have on her, and the influence she might have on other words—old, rare and ugly—as she grows into a woman” (Lithub).

Of course, neither Esme nor her Dictionary of Lost Words ever existed in real life: they are purely fictional. However, it is exactly through the presence of this invented character that the novel manages to highlight an absence, a gap in the historical narrative surrounding the Oxford Dictionary. As readers, we are made aware of Esme’s fictionality: we know that she never created an alternative dictionary listing all these lost and forgotten words. However, we can’t help but wish that she had.

Changing the Facts: Good or Bad?

What the above discussion and my previous two entries on the topic were hopefully able to show you is that the issue of (the need for) historical accuracy is one that doesn’t have an easy solution. There is no universal “yes” or “no” to the question of whether or not deviations from generally accepted ‘facts’ are a good thing. All we can do is look at individual works of historical fiction and consider how their factual inaccuracies contribute to the narrative: what purpose do they serve? What could have been the author’s intentions for changing them? Do they distort events in a way that could possibly harm or do injustice to the actual, historical persons or group(s) of people involved? Or, perhaps, do these fictional elements, in their inaccuracy, point to aspects and parts of historical truth that are oftentimes wilfully overlooked and ignored?

History is a topic that will most likely never seize to amaze and intrigue us – and for as long as this is the case, writers will keep trying to give us an insight into all its glory and shame. They will keep changing the facts, filling the gaps, adjusting the story to mix education with entertainment. At times, such untruthful depictions can be dangerous when they are ideologically tainted or when they unjustly misrepresent events or people. However, in other instances, such works of historical fiction can show us that the truth doesn’t (only) lie in factual accuracy. Sometimes, it can be found in what could, might or should have been, or in the absence of what was there, or the presence of what wasn’t. And sometimes, a bit of fact-twisting is merely a way to make an interesting story even more interesting, so that a reader’s boring Sunday afternoon can become an exciting adventure.

After all, who can argue with that?

Sources:

“Bridgerton: ‘It's Not Colour-Blind Casting, It's Colour-Conscious Casting.’” BBC Scotland, Accessed 1 October 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/4GNscF9LQmptPNKHNZzbTzL/bridgerton-its-not-colour-blind-casting-its-colour-conscious-casting.Forrester, James. “The Lying Art of Historical Fiction.” The Guardian, 6 August 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2010/aug/06/lying-historical-fiction.

Kelsey-Sugg, Anna. “How the Oxford English Dictionary Was Brought to Life in a Rustic ‘Scriptorium’.” ABC Radio National, accessed 1 October 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-09/history-of-the-oxford-english-dictionary/12010628.

Williams, Pip. “A Secret Feminist History of the Oxford English Dictionary: Pip Williams’ Alternate Story of the English Language.” Lithub, accessed 1 October 2021. https://lithub.com/a-secret-feminist-history-of-the-oxford-english-dictionary/. Images: https://variety.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Irregulars_Vertical_Main_sRGB-1.jpeg https://occ-0-2794-2219.1.nflxso.net/dnm/api/v6/E8vDc_W8CLv7-yMQu8KMEC7Rrr8/AAAABQU8LfvflLbWoWwznrf2GXx6lAdu0AcKYU49aiTtcoQnQZMCsLhqaDiWF2ttWYqDhtScSso3QEnm9sAaw-KomUcwVbHy.jpg?r=c70 https://cdn.waterstones.com/bookjackets/large/9781/7847/9781784743864.jpg