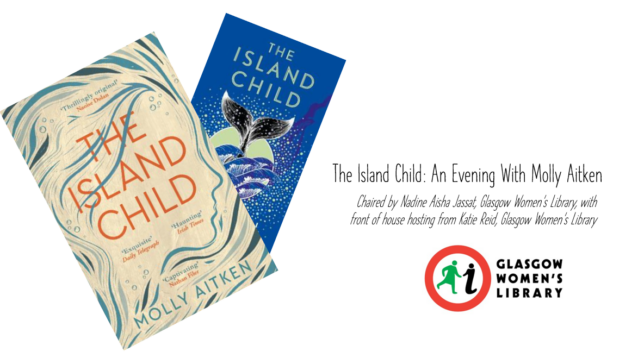

‘Stories Yet to Be Told’: Glasgow Women’s Library Chat to author Molly Aitken

We recently had the opportunity to spend an evening with author Molly Aitken, and a beautiful audience of guests. Molly joined GWL National Lifelong Learning Development Worker Nadine Aisha Jassat to discuss her debut novel, The Island Child, published by Scotland’s own Canongate Books, and recently longlisted for the Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award. The Island Child is a haunting and atmospheric story exploring mothers and daughters and the story of Oona, both as a child and as a mother herself, navigating the storms and confines of her life, of the harsh bind of patriarchal power, and of the Island itself.

Here’s a few highlights from the night’s Q&A, with the italics and ‘N’ being the questions from Nadine, and below them Molly’s answers.

We began by talking about how the first seeds in a love for writing are often planted in our younger years. N: How did these seeds influence the Island Child?

I was told so many myths and folktales growing up. In Ireland it’s quite common – I’d go to the pub with my Mum who used to sing and I’d hear all these stories about ghosts or the little people, and quite a few ended up in the book. But mythology and folk tales have always been my route into writing, because they were the first stories I ever heard.

N: Why did you want to write a feminist retelling of Persephone and Demeter?

People usually know the story for how Hades steals Persephone from her mother and takes her to the underworld – but that wasn’t really the part of the story that interested me. I was much more interested in a mother losing a daughter and how that feels. It felt to me that the story had been told through quite a male lens, and that element that interested me hadn’t been taken into consideration enough. So, I wrote the novel as an answer to that – to continue the story and evolve it, to consider women more.

N: The book features a sense of storytelling magic between women, countering the harm silencing does. Can you tell us a bit more?

That’s really what the whole book is about. Throughout the novel, Oona, the main character, has to learn to speak her truth and tell her story. That’s something that her mother, Mary, doesn’t learn to do, and Oona knows very little about her. At the time that Mary was growing up, women didn’t have much of a voice and weren’t supposed to speak about their bodies or what they were thinking, except maybe to each other. So, The Island Child is really about the freedom that you get from expressing your truth and your stories, and how that allows you to move beyond the shame that the patriarchy has put on you, and allow you to step beyond it. Throughout the story Oona is telling her story to her daughter Joyce – so Joyce is going forward with more power than Oona had, and more than Oona’s mother had, because she has this story now, she knows what has happened to her mother, and that gives her strength.

N: This resonates with us at GWL, who understand that women’s stories are intrinsically bound with women’s liberation.

Exactly. Oona tells her story as a myth, and I write my own stories through fictional characters. Both for myself and Oona fiction can be a way to tell the truth at an angle. It is perhaps easiest to tell your story as a folktale or fiction. Maybe the ‘real’ story can then come later out of that.

N: The island itself is almost a character in the book, and it intertwines with the people, too. Can you tell us more about how nature and the island function in the book?

From a writing perspective, an island felt like a good place to set a story: because everyone is trapped, they can’t get away from each other, in an almost ‘pressure cooker’ like situation. It felt like easy writing to have all the characters stuck together in this way. The elements and nature on an island are also so harsh. This makes life even more challenging for the characters – sometimes they are struggling for food, the weather can be terrible, sometimes the ferry can’t get there from the mainland – that really affects who they are as people, it affects their personalities and how they interact with each other. Such a small community means that everyone is watched and it is hard to keep anything to yourself. This really represses the women and for Oona it makes her long for freedom, for a new place where she can be and discover herself without judgement.

N: You write in The Island Child that ‘a truth is what everyone agrees is a good story,’ and, later, that ‘tales grounded in truth are always more meaningful’. Can you share with us a bit more about how truth works in the novel?

I grew up in a small village, and there was a lot of gossip. This has always fascinated and frustrated me. When you tell stories about other people, you don’t really know what was going on in their heads – even if you know the exact events, you can’t tell what it’s like to be them and why they make the decisions they make. Oona is a classic example of a girl and woman whom a small community would gossip about because she doesn’t always stick to their rules. So, part of The Island Child was having a woman speak and tell her story in her own words: and that then becomes her truth. As a writer, you can enter into someone else’s story and that truth through writing it. Until you truly try to understand how it is to be someone else, you can’t really assume to know the truth. Writing and reading gives you a window into other people’s experience and truth and that’s why it’s so important.

N: Can you share advice for anyone wanting to write their own retelling of a myth or folklore?

Madeline Miller who wrote Circe said in an article I read recently that when she was a child she was reading The Odyssey and she felt that she didn’t believe quite how Circe was depicted – she didn’t believe that a woman who had been so powerful would suddenly out of nowhere throw herself at the mercy of a man. If you ever have an impulse like that follow that. Retelling and revisiting myths we don’t know that well, which are often ones about women, would be a very exciting place to start, too. I would also say don’t be afraid to make it your own, make it contemporary if you want to, or be as loose as you want – for example just going with the themes. Your retelling might take place in space or gender swap. How brilliant would that be?

Audience Question: How do you go about writing your book? Do you jot down ideas before you get started?

A novel, for me, is many ideas coming together at once and melding. I have to work with them for quite a long time before they form something coherent. I work with lots of new ideas at one time and go with the flow with it and see what comes. I’m not a plotter; I like to go with the characters and see where they take me. Go with the ideas you have and start writing, and see where it takes you!

N: Can you tell us about your next project that you’re working on?

My next book is retelling a true story about a woman in medieval Ireland who was, as far as I’m aware, the first woman formally accused of witchcraft in the UK and Ireland. As with so many cases, there was really no evidence of her doing anything untoward – but she was incredibly independently wealthy, and the church at the time and one particular Bishop, didn’t like that. Everything that has been written about her has been written by that Bishop, and so I’m rewriting with her voice, exploring what her experience might have been! There are many silent voices from history, a lot of them are women. This is also a ripe place to find new stories for fiction.

N: It reminds me of how, for writers, writing can be an act of justice – a way of righting a wrong.

Yes. She didn’t get to speak much in her own life and hasn’t throughout history. And as women, there are so many opportunities to do that now – including by rewriting and re-examining myths and legends. So many of our stories are yet to be told.

Thanks so much Molly for answering our questions! You can find out more about Molly and The Island Child here.