Museum curator Jenny was one of six very lucky GWL staff who took part in a British Council-funded cultural exchange to Nairobi in October 2019. For more photos and reflections, check out the #GWLKenya hashtag on Twitter.

As our memorable week began to unfold, one of the most striking things about the city for me (aside from the strangely unsettling marabou storks atop the acacia trees) was an all-pervasive Indian influence. From deliciously aromatic curry dishes to stunning Sikh temples and the punctuation of daily calls to prayer from Islamic mosques across the city, Indian culture felt like a pretty big part of Nairobi life.

The reason for this fell into place when we visited the Nairobi Railway Museum. Nairobi was founded as a rail depot during the construction of the British-owned Uganda-Kenya Railway, linking the interiors with the port of Mombasa. Most of the railway labourers were indentured servants from British India.

A large wall-mounted relief map drove home the scale of the British Empire’s expansion as we were told of Queen Victoria’s ‘gift’ to neighbouring Tanzania – a quick border change to ensure that British-ruled East African countries had their ‘fair share’ of mountainous tourist attractions! Yes, Kilimanjaro used to be in Kenya.

Colonialism underpins everything. That’s not an overstatement. I had anticipated feeling its impact, not least in the problematic (and frequently racist) public library collections inherited by our sisters at Book Bunk but it was only once there in the city that I fully grasped how deeply embedded colonialist attitudes and practices are in all aspects of life.

Before travelling, I re-read The Challenge for Africa by Wangari Maathai. I was struck by her description of the erasure of collective memory across Kenya. Traditional ecological and sustainable practices were stripped away by British governance, rendering the Green Belt Movement absolutely vital to Kenya’s environmental conservation and climate resilience.

It was a joy to stumble across Maathai’s first ever tree nursery while relaxing in the beautiful Karura Forest. Later in the week we were privileged to meet her daughter, Wanjira Mathai, who talked about the importance of the Wangari Maathai Foundation in instilling leadership skills in young people to promote creativity and courage and break the post-colonial chain of political corruption.

Unable to sleep on the Dubai to Nairobi leg of our journey, I had listened to the Otherwise? podcast. In Episode 109, Brenda interviews digital heritage specialist Tayiana Chao about the loss of cultural heritage in post-colonial Kenya. They discuss the cultural disassociation created by centralised models of custodianship built on a foundation of imperialist society.

Fascinating and thought-provoking as they were, our visits to the Kenya National Archives and Nairobi National Museum did little to dispel this perspective. Sadly, we didn’t have time to check out the Museum of British Colonialism but I’d urge you to take a peek online.

Even an uproariously joyful live recording of The Spread Podcast was spiked with a shaming reference to the conservative patriarchal system introduced by the British. Where same-sex relationships and cross-dressing, for instance, were traditionally an accepted part of tribal society, post-colonial Kenya’s LGBTQ+ community suffers stigma, discrimination, criminalisation and violence.

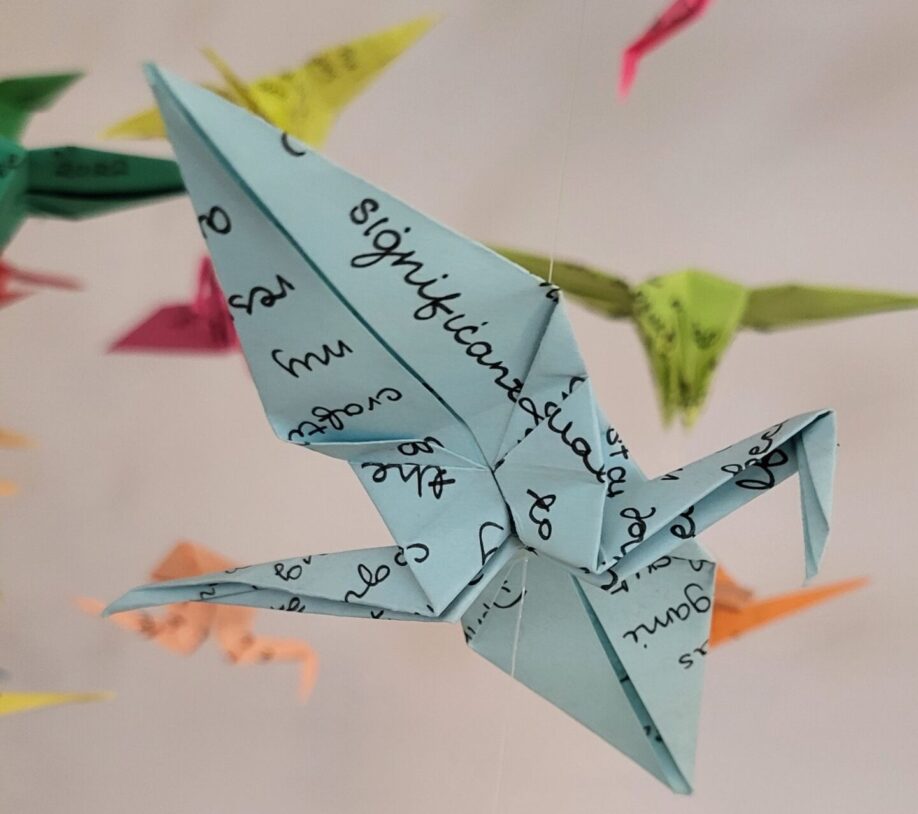

Throughout our time in Nairobi we met many incredible individuals and organisations (you can meet a few in Our Book Bunk Friendship) who were working tirelessly to counter the destructive legacy of colonialism and the erasure of their cultural heritage.

At home in Glasgow, we too need to consider how we can best recognise this legacy and reflect its impact in our collections. There is so much hope for the future but we should be forever mindful of the past and how it affects the present.