Our Mixing The Colours Conference on Friday 20th March was the culmination of 18 months of research, workshops and discussions.

I thought I’d share my presentation/speech from the day to further share the thinking behind and importance and impact of the project.

Rachel Thain-Gray, Project Development Worker

Through this project we hope to address and challenge the stereotypes of women as victims of sectarianism, to have women be more visible in this debate, to expand the issue out from football and to empower women to challenge and take action against it in ways that feel safe and powerful.

To date the project has validated women’s experiences, raising confidence levels and fostering women’s active citizenship and we look forward to continuing this work for the next year thanks to the Scottish Government.

At the inception of the project we were struck by lack of literature by women or about women on the issue of sectarianism and focus groups of women said that a dedicated book and workshops would help them speak about the issue in a safe place. So it’s been a process of consultation and active participation from the start.

During 2013-2015 we ran 46 workshops in communities nationally across Scotland with over 250 women. From Bridgeton to Brora to Dunbar and Edinburgh. We interviewed women for our film, we ran a writing competition, gathered numerous pieces of creative writing and ran discussion groups.

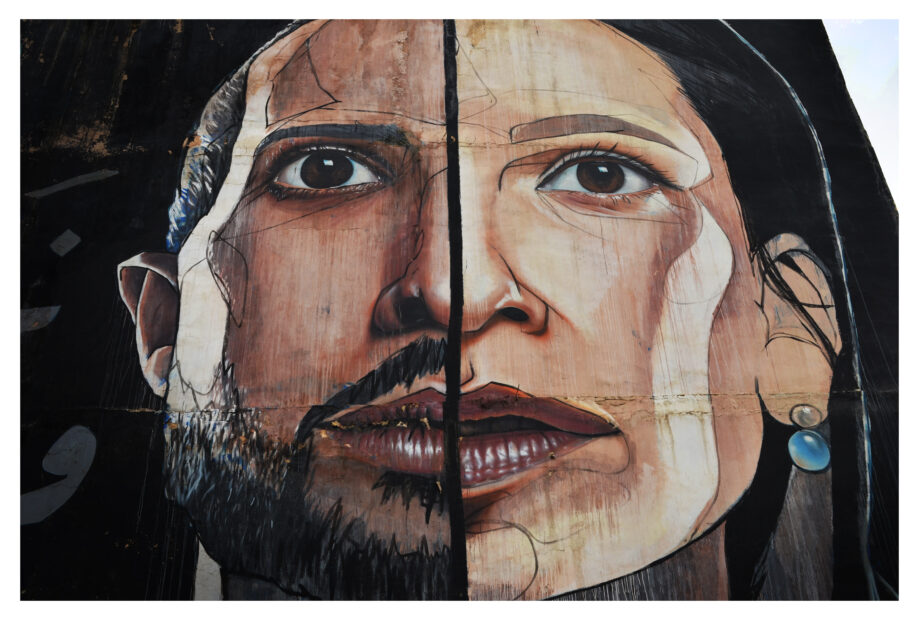

We sought to expand the issue out from Scottish indigenous Protestants or Catholics to reflect the diversity of Scottish society and explore how sectarianism impacts everyone.

We also recognised the diversity of catholic and protestant religious and cultural groups and that these women were not a homogenous group who would all have the same perspective.

We approached women in a non-judgemental way to open up debate and encourage learning and empathic responses to people’s experiences.

This approach enables women to develop insight through conversation and activity in mixed groups. By sharing both catholic and protestant stories we encouraged understanding and women shared their fears and prejudices.

The stories and poems you’ll hear today provide a remarkable insight into the experiences of women that have historically been overlooked.

The project has enabled and captured the voice that women have not had, telling both overt and subtle stories of bigotry and violence that were not spoken or asked about previously.

Throughout the project we gathered accounts of discrimination, the direct result of religious bigotry against Catholic and Protestant. We also heard how sectarian bigotry intersects with transphobia, homophobia, misogyny, racism and hate crime.

68% of 110 learners said that they had experienced sectarianism but defining the experience was of key importance.

Some participants questioned whether they considered sectarian since they themselves were not the direct victims of discrimination or violence but there was no doubt they had experienced fear and intimidation.

This leads us to believe that the experience of sectarianism is much wider than an issue of “victimisation driven by discrimination against a religious ‘other’.”

Sectarian behaviour at home and in public spaces affects women as control and fear, both in the legacy of their childhood and in the present day. Within this there are different kinds of sectarianism and its by-products being experienced.

These includes private emotional or psychological control of thought, values and behaviour, carried out by both male and female family members, and overt control of public spaces through fear, intimidation and territoriality, generally undertaken by men.

The emergent themes of the project show a need for a new contextualisation of the term ‘sectarianism’ and a wider understanding of how it is experienced.

Within the public spheres of their communities some women told us that they would be unlikely to challenge sectarianism on the street for fear of violence, hesitant to challenge it at home for fear of family conflict and reluctant to challenge it on social media for fear of misogynist abuse.

Public and private personal safety is a key concern.

This fits within women’s wider experience of general safety in their homes and on their streets in a context of anti-social behaviour, hate crime and gendered violence. Working as a group they found power in numbers.

Throughout the project we shared the growing collection of stories and poetry with groups. Women said that collective contributions, using creative methods, gave them a safe and powerful voice. So a significant aspect of the work has been this collective action.

These stories are the tangible outcome of women’s collective action and the book gives weight and importance to their words and experiences. It is a starting point for the future and I’m really heartened by their courage and proud of the work that they will share with you today.

The question of women’s position on sectarianism has come up at a few public events I’ve attended recently.

And the lack of awareness and tendency to make assumptions bolstered for me the importance of our research. From the start we knew that the only way to find answers was by asking and listening to women themselves.

There have been three key pieces of research released in the last few weeks by the Scottish Government one of which provides data evidence on attitudes towards sectarianism. Data evidence provides tangible numbers, it is reassuring in its factual nature.

But much of the evidence gathered even where it is assimilated in cold hard numbers is based on perception.

Having worked in the equalities and gender-based violence, perception is as important as data. Because much of what happens to women isn’t recorded as crime statistics or even acknowledged in our society. You only have to look at the accounts in the Everyday Sexism Project to see this.

During the course of our work, women told us they felt unsafe. How do we quantify this in a cold, hard way?

We know that women under report gender-based crime and sectarian incidents are no different.

Where a woman told us she was called a fenian bitch in the street during a parade, how likely was she to report it? How would it be recorded if she did? Is it a sectarian crime or a normalised act of misogyny? How likely is it that this would be pursued as a crime either way?

Sectarianism is experienced within a context of women’s safety in general in public spaces and how they experience public life.

Women told us that they modify their behaviour on match and parade days to avoid unsafe situations and places.

Women are stopping their children from going out to play, shopping for food prior to matches, choosing their own and their children’s clothes to avoid negative attention. They are staying home.

If women are using avoidance techniques their experience of public life is at stake. And this fits into our gendered experience of public spaces, streets named by and for men, the dominance of male public statues and plaques, that where women do experience themselves are in the negative constructs of advertising billboards, newspaper headlines, lads mags and page 3…I could go on.

So what is women’s position on sectarianism? Until now women were publicly the victims and in the undercurrent the maternal perpetrators.

Where women are identified as perpetrators we must explore the context in which it occurs. Women may appropriate the dominant male story in their family, church or society as a way to align themselves with the patriarchal construct, a way to experience some form of power where none exists in their own lives.

Where women practice forms of exclusion or ostracisation in a family on the basis of religion they may be taking an instrumental role to ensure their own inclusion and ultimately safety, since they have so much to lose by not being a part of it.

More research with a feminist analysis needed in this area.

When we look at the outcomes of the Attitudinal Survey 58% of people said that the best place to tackle sectarianism was in families. 55% said schools and 50% said football clubs or authorities.

I think it’s important that the question in the survey is not interpreted to appropriate blame or place unreasonable responsibility on women and particularly mother’s shoulders.

We must understand sectarianism as a patriarchal construct that must be acknowledged as part of the dominant fiction of masculinity and challenged by men and fathers in their families.

Parents and care-givers need good support and opportunities to tackle sectarianism at home, they need to be involved in intergenerational sectarian education programmes in schools.

And ultimately football clubs and authorities need to be held accountable for sustaining permissive public environments for sectarianism and definitions of masculinity. Without it children receive a mixed messages and parents and schools are undermined.

Mixing The Colours sought to expand the lack of research on women’s position in sectarianism. Our approach aimed to empower women to find their own solutions for tackling sectarianism, and I think they are.

Every workshop we held was noise-filled as women thrashed this issue out. Every discussion threw up new questions. Each question unpicked the complexities of sectarianism to reveal new ones. It was honest, it revealed depth, history, psychology, identity.

And it was all explored without ego.

It was a debate, entered into with openness, a willingness to share and a willingness to learn. They didn’t need to resolve it. The conversation alone was enough.

And it’s not just the learning that the women who will speak to you today bring to this issue. But the learning they take into their homes to share with their families and friends.

This is learning that changes the path of generations. And the bi-products of the book, film and attention they receive in the media are all safe, non-confrontational ways to speak with their families where conversations may not feel comfortable or safe.

But to enable this kind of action it’s important to create opportunities, space and time for women to think, speak and analyse their experiences.

And if we are going to support women to speak then it’s all of our responsibility to hear them.

We were approached by a few members of the press in the last fortnight and two out of three of them decided that there wasn’t enough interest in the ‘woman angle’. Public awareness remains in the media’s hands and poses a significant barrier to women’s voices being heard.

The women who will share their stories with you today have changed how we move forward on the issue of sectarianism, they have laid the ground stone, they are the authors, they are the speakers, they are the experts in their own lived experiences. And they are the change we all want to see.

If you would like to get involved in Mixing The Colours during 2015 and 2016 please get in contact via rachel.thain-gray@womenslibrary.org.uk