Last week was Banned Books Week, and we held an event in partnership with Scottish PEN to highlight the importance of freedom of expression. Banned Books Week was launched in the US in 1982 in response to a sudden surge in the number of challenges to books in schools, bookstores and libraries. It encourages us to celebrate our freedom of expression, and stand up to censorship.

I’ve asked our wonderful learners and borrowers to review some banned books for us, and here are what we’ve got so far – two fantastic reviews by Mary. They really capture what Banned Books Week is all about. Read on and be inspired….

We have plenty more banned books waiting to be reviewed. Pop in and pick one up! (But remember we will be closed from 14th Oct to 11th Nov to relocate).

The Proof of the Honey by Salwa Al Neimi, translated by Carol Perkins

The book was first published in Lebanon in 2008. As the author admits she expected, it was banned in her native Syria as well as in many other Arabic speaking countries. The reason? It dealt with the subject of sex – taboo! In addition, it was a woman, an Arab woman, daring to do so. This English edition was published in USA. As with any translated book the reader is reliant on the accuracy of the translation. One cannot help wondering in this case that translation of the Arabic may have lost original nuances. However, this is the book in review so one must look at it as it stands. This edition was withdrawn by Apple from its itunes bookstore because of the ‘inappropriate’ cover. If this cover is inappropriate then so are many major works of art now on display in public galleries.

The cover clearly states this is a work of fiction. Maybe it is, but on reading it I was drawn into believing the ‘I’ in the narrative is the author herself. If not wholly so then at least in part, for she had certainly put much of her academic knowledge in, and personal love of, early Arab literature dealing with the subject of her own book – sex. Nor does this erudition stop there for she also references comments, advice, descriptions of authors of erotica from other cultures,going so far as to suggest the reading of all such texts would be of great benefit to the Arab world in general.

This short book is divided into ‘Gates’ rather than chapters, each gate dealing with a different aspect of how sex permeates all aspects of our lives. The use of ‘gates’ is very apt as what follows is an opening into a sphere with which many readers will not necessarily be familiar, either on content or openness. The book speaks freely of a journey of finding ‘self’ through the narrator’s personal journey of sexual encounters. Roles of men and women, seeming double standards, hypocrisy – all are addressed.

The author’s ‘Enlightener’, referred to as ‘The Thinker’, I have, in my own mind, equated with ‘Soul mate’ – the person who facilitates our ability to advance our search and achieve our goals. Al Neimi speaks of coincidences in this area although I would use Jung’s term of synchronicity. Everything we are already exists. It just needs revelation.

One of the criticisms initially levelled at the book is that the style varies from academic to less formal. Personally I did not find this in any way impeded my understanding or enjoyment. I particularly enjoyed the comments on, and the discussion of, the use of anatomically correct terminology when talking of sex, sexual action or those parts of the body immediately associated with such. In English we have such words, often unacceptable in polite circles, but certainly not banned! One is mindful of the D.H. Lawrence fiasco in 1960.

Although there are a lot of stories, anecdotes might be a better description, in the book, it is not a story in the usually accepted sense. It certainly doesn’t have a middle, beginning and end. It is an ongoing story and should give encouragement to both women and men to be true to themselves.

The book may be considered by some to be a promotion of sexual promiscuity. It isn’t. It’s a search for knowledge, fulfilment. freedom, each in its widest sense. Neither is it pornographic. There are descriptions of ‘fucking’ but these come under the aegis of erotica and are not gratuitous.

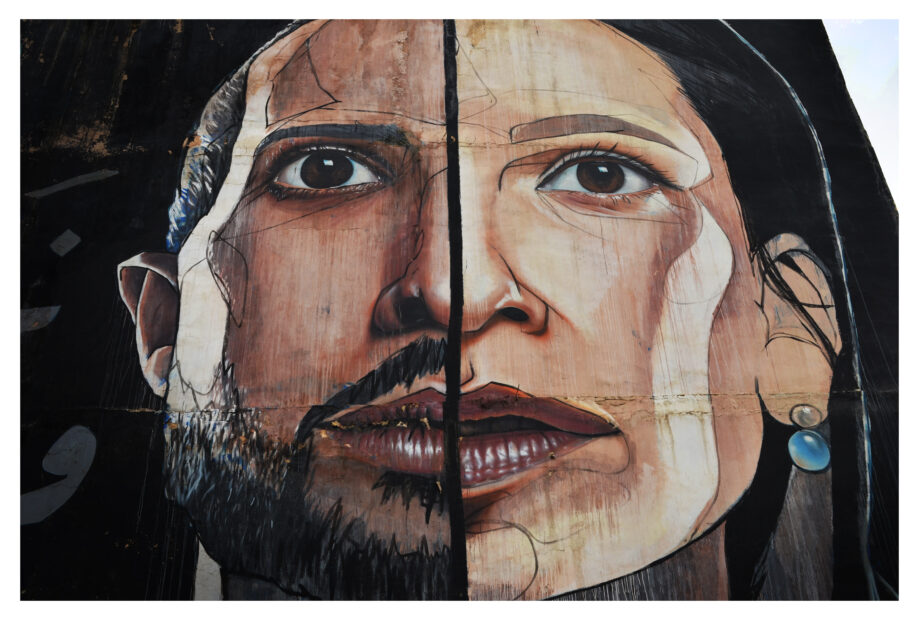

Salwa Al Neimi dared to lift a metaphoric veil on sex and, hopefully, has opened some gates along the way.

To Kill a Mocking Bird by Harper Lee

Written during the late 50s, published 1960, awarded prestigious Pulitzer Prize 1961, translated into over 40 languages, sold over 30 million copies, never out of print, one of most challenged books, BANNED!

Hearing this book had been banned I thought, ‘That’ll be south USA, because it criticises the state of affairs existing in the South during the 30s.’ But this was how it was and Lee grew up in Alabama where the book is set. Who better to write about life there at that time? Imagine my surprise and consternation on discovering the history of this banning or attempted banning. Yes, it was in USA, but spanned the entire country. As early as 1966 the use of rape as a plot device was described as immoral. In the 70s the book was condemned as a filthy, trashy novel, using profane language, (damn, whore lady), didn’t condemn racism ‘enough’. In the 90s and 00s attacks continued, use of the word nigger unacceptable, racial slurs degrading to African-Americans.

Lee probably knew of the infamous 1931 Scottsboro’ case (Alabama), the circumstances of which resonate in her book in the trial of Tom Robinson , a black man accused of the rape of a white girl, a capital offence in Alabama. She would also have been aware of the total fiasco of the Emmett Till trial (Mississippi) in 1955. Here again the trial of Tom and the jury’s decision resonate but Lee makes two crucial differences. The length of the deliberation and the fact that one juror wanted to acquit. The verdict was not a foregone conclusion. The attempt to lynch Tom may also owe something to the 1935 lynching in Miami of Rubin Stacey, seized by a mob from sheriffs’ deputies, and hanged for allegedly attacking a white woman. These are not fiction. They and many similar are fact.

People who try to ban this book don’t know their history, or maybe they do and feel guilty about it.

It is my argument that the accusations levelled display a total misunderstanding of the book. The narrator is the young girl, Scout, a tomboy as was Lee. We see, through her eyes and the innocence of childhood, the drama of the reality of a black man accused of the rape of a white women. Atticus, Scout’s father and a lawyer – as was Lee’s father – despite loss of respect in the white community and threat of violence remains true to his beliefs and goes ahead with his defence of the accused, Tom Robinson. Despite the climate of the time Atticus believes that all are entitled to respect and justice regardless of their station in life or the colour of their skin. Here we see a ray of hope through Atticus’ stand against injustice. Dolphus Raymond and Miss Maudie make the ray a little brighter. There is a moral condemnation of racial prejudice and Lee places it in the 30s, some 25 years before the peak of the Civil Rights Movement. The blatant hypocrisy of Aunt Alexandra’s Missionary Circle and her attitude towards White ‘trash’ display a more general prejudice.

There is a degree of violence in the book but it is in context and never gratuitous.

Again it reflects a time of extreme violence. It is the violence and injustice that leads to the loss of innocence of Jem, Scout’s brother whose trust and faith in his community id shattered. He determines to become a lawyer and fight injustice. Surely a positive vision of the future. But the book is not a polemic and shouldn’t be judged as such or criticised for not being so. We must always be objective, looking at situations in the context of the ethos of the time. We can say that we have learnt, we are now more civilised, that these things are wrong and shouldn’t happen anymore.

In 1998 Jerome Byrd was murdered in Texas because he was black. Two of his murderers, white supremacists, were executed. In 2009 James Anderson was murdered by at least 7 teenagers who went out as a matter of course to ‘hassle niggers’.

Lee’s book should be read by everyone. There are lessons to be learned from it, even after the 50+ years of the book’s existence.