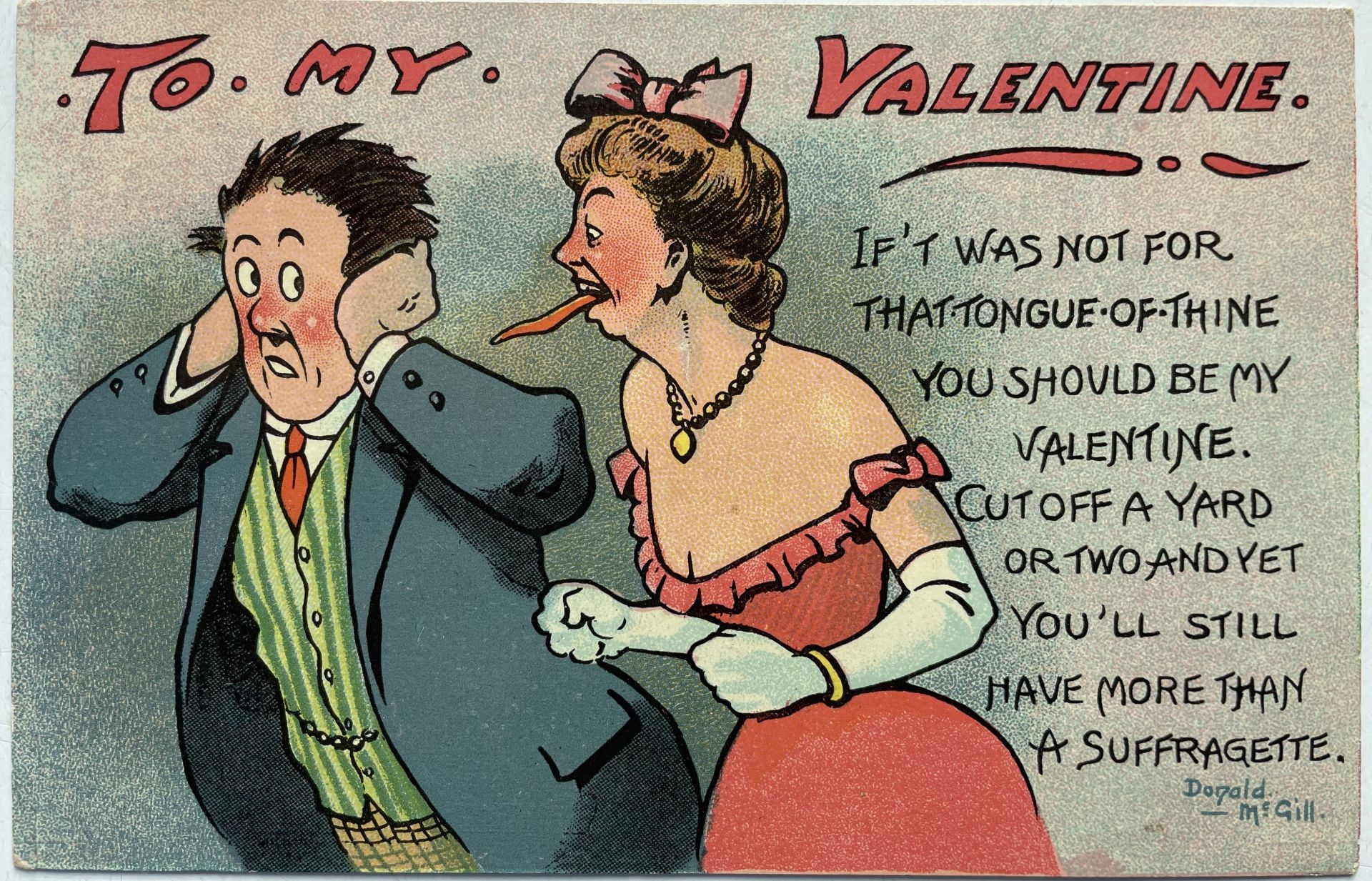

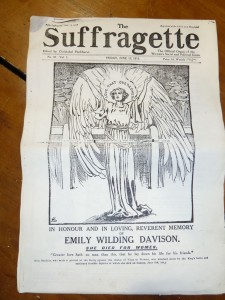

Sammy DiFolco examines the life of Emily Wilding Davison through The Suffragette newspaper, which is part of GWL’s Women’s Suffrage Collection.

The eighth of June marked a century since the suffragette Emily Wilding Davison died under the hooves of the king’s horse at the 1913 Epsom Derby. At Glasgow Women’s Library we remembered a woman who gave a great sacrifice in the hope of a better future for future generations.

In her early years Davison was a bright woman in a time when educational opportunities for women were scarce. Davison attended Kensington Prep School where she became one of the first students of the Royal Holloway College studying French, German and English Literature. A year on she would have to pull out of Royal Holloway due to her father not leaving sufficient funds to pay the term fees. Davison then found work as a governess to enable her to complete her studies at St Hugh’s Hall, a women’s college founded in Oxford. Despite achieving first class honours, Emily was not allowed to graduate. Oxford degrees were closed to women in spite of their academic achievements. After leaving college Davison went on to become a school teacher enabling her to make enough money to return to education at The University of London where she finally graduated with a first class honours degree in English Language and literature.

Davison’s spare time was dedicated to social and political activism. In 1906 she joined Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). In 1909 Davison gave up teaching to devote herself to The Women’s Suffrage Movement. She became increasingly militant in her activism. Some of her actions included breaking windows and setting fire to post boxes. Davison was also well known for breaking into the House of Parliament for the 1911 census . Davison hid in a cupboard overnight so she could give her place of residence as The House of Commons. During her time in prison she went on many hunger strikes being force fed a total of forty-nine times over the course of nine prison sentences. In 1912, in protest against force feeding, Davison threw herself over the railings of the prison stairs being caught only by a piece of netting that Emily later said about this incident “the idea in my mind was one big tragedy may save many others.”

The Epsom Derby of June 1913 is where Emily Wilding Davison stepped out onto the race course and gave her life, and name, to the suffragette cause. Much confusion clouds whether or not Davison’s death was intentional on her part or not. She purchased a return rail ticket and a ticket to a suffragette dance later that evening which has been used to support the argument that she did not intend to lose her life that day. However, had Emily survived then she would be well aware that she would be arrested and consequently not get to use her train ticket home. According to eye-witnesses, Emily was seen ducking under the railing and going towards the King’s Horse, Anmer, where she tried to grab hold of the reins but was knocked over by the horse. Although two WSPU flags were found in her possession it is unclear if her intention was to grab hold of the reigns of the King’s Horse to attach the WSPU flag so that upon the race finishing the Kings horse would be seen flying a flag in favour of Women’s Suffrage.

Emily died four days later in hospital due to injuries inflicted by the incident She never regained consciousness but she received many ‘hate’ mail and enquiries into whether the King’s horse has survived its ordeal. However on Saturday 14th June 1913 six thousand women marched from Kings Cross to Victoria pausing to hold a memorial service for her. Her coffin dressed in the WSPU flag was laid to rest with the phrase “Deeds not Words” inscribed on her headstone.

In Glasgow Women’s Library we have two original copies of ‘The Suffragette’ Newspaper and a colour reprint published five days after Davison’s death that quotes a fellow Newspaper as regarding the act of martyrdom as “A petty incident which had marred an excellent race.” If you would like to find out more about GWL’s Women’s Suffrage Collection, which includes these documents, then pop into Glasgow Women’s Library to see one of our archivists Laura or Lindsey.