This month Anni reviews:

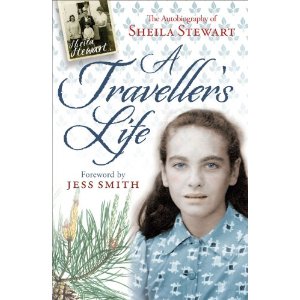

A traveller’s life by Sheila Stewart

Maybe this book is not like other people’s biographies. But it has to be different…because a travellers’ life is different from anyone else’s.’ And so it is. A Traveller’s Life by Sheila Stewart is a life’s story we should know about. The joys, tensions and traditions of a member of one of Scotland’s best known Scottish Traveller families provides a welcome antidote to the negative press reports of Traveller conflicts with settled or ‘scaldie’ communities such as the long running Dale Farm dispute and of the extravagances displayed in Channel 4’s My Big Fat Gypsy Weddings.

Born in a stable in Blairgowrie ‘into a world of poems and stories and songs’, described as ‘the voice of Blairgowrie… a raven-haired beauty, envy of many traveller lassies and the dream girl of the laddies…with a perfect voice’, Sheila’s spirit as a tradition bearer for travelling people was recognised by her uncle Donald when she was only five years old. Sheila’s autobiography is also full of songs and tales from her Traveller community and is the next best thing to hearing these tales told with the smell of wood smoke in the air. The transience of the Traveller way of life with its deeply felt communality is held together by the long bonds of this shared lore and spoken in Cant. Sheila also provides a glossary of Perthshire Travellers’ Cant.

Sheila and her family moved around a great deal, earning money by raking dumps, gathering rags and selling them, seasonal farm labour, lifting potatoes, berry picking, making, hawking and repairing tinware, basins and pea strainers. Despite living with the deeply ingrained prejudice and casual violence of people in settled communities and the sheer grind of making a living, there is no resentment, not a trace of self-pity and a great deal of black humour in this book. ‘Although we were persecuted in Blair, and got beaten up for being travellers, my mother loved Blairgowrie, and I would like the people of Blair to remember that.’ Travellers were sustained by loyalty, a shared oral culture and language. Storytelling and ballad singing, woven into the fabric of Traveller life, carried the values of a nomadic community living on the margins of settled society. Sheila recounts many of these tales in her book: morality tales about how to be human and what sort of human to be, songs and stories celebrating the close relationship Travellers have with nature and its mysteries, fantastic tales full of spirits and demons, lighthearted fables full of fun and high jinks. Tales told to instruct and to entertain or given as gifts, created a welcoming hearth shared by a seemingly endless stream of characters flowing with the seasons and the harvests.

The customs and daily habits of Travellers, deeply rooted in history, experience and nature, kept its members healthy and often alive in the absence of medical treatment. Remedies were derived from generations of accumulated knowledge: the healing properties of plants and herbs – how to tempt a tapeworm from inside someone’s stomach with a piece of meat placed on their tongue – how to mix a simple and highly effective earth and water poltice held in place with dock leaves to treat someone’s badly scalded legs – the importance of cleanliness and never washing anything in a sink and always using a basin.

Although not always a wholly biddable daughter, independent and highly intelligent, Sheila describes how her life, like other women’s in her community, was mainly defined by others and her expectations clearly proscribed. Loyalty to parents and family were extended to her husband on marriage. Marriage and childbirth were not straightforward – although Sheila’s husband Ian was not a Traveller, he was accepted by her family and became a willing convert to the way of life. Ian’s jealousy and fondness for drink [peeve] were clear even before they married and he often blew his wages in the pub with his friends. A volatile and occasionally violent man, Sheila describes theirs as a ‘peculiar kind of love…very deep. We couldn’t agree, yet we couldn’t stay away from each other.’ Iain ‘was not husband material. Although he adored his kids, he wasn’t very family-oriented. But I loved him and I was his wife. I had made my bed, and I would have to lie in it.‘

Acting without her consent, Sheila’s mother and husband gave permission for her to be sterilised, ‘I had no say in the matter of my own body…I was used to my life’s decisions being made for me and so I just accepted it.’ She had wanted to breast feed her newborn daughter but when she came home from hospital the baby was already being bottle fed and Sheila’s milk had gone. ‘I was so sad about that.’ Sheila was not allowed to choose any of her children’s names. Women with children still had to do their share of the work – even during potato lifting. Sheila and her husband Ian worked together, dividing the field up between them and keeping a fire at one end to boil kettles for tea and to cook and keep warm when it was cold. Sheila describes having one child walking about the field, one in a basket and another in a pram while she worked in the field.

Obligations to her husband led to conflict about her performing at home and abroad. Ian’s reluctance to let Sheila travel was usually overcome by the prospect of the money she would earn. The contradictions in Sheila’s life were well summed up by this conversation with her father, a noted piper, Willie Stewart, ‘You were in America, met royalty, and were made the blood-sister of a Comanche Chief. Then you come home and go raking a midden, and give your blood to an auld traveller woman to glue her clay cutty [pipe] tegither. How do you feel about that? Daddy, I was born a traveller and I will die one, I prefer travellers any day, they are my folk. I will never change.’

After the death of her mother Belle, instead of becoming a ‘bingo granny’ Sheila started performing again and felt ‘liberated for the first time in her life, and it was a great feeling’. She could sing where and what she wanted and soon overcame her anxiety about speaking to audiences directly as her mother used to do. Against the advice of some academics, Sheila wrote her mother Belle’s biography ‘Queen amang the heather’ and has now written her own.

Now in her seventies Sheila is rightly acknowledged as one of Scotland’s great folklorists, teaching and performing all over Scotland and abroad and still speaking out on behalf of Travellers and the continuing prejudice they face. Sheila has found common ground with traditional singers and musicians from other nomadic cultures around the globe, who also experience discrimination at the hands of settled communities. Sheila has rightly been inducted into the Scottish Traditional Music Hall of Fame – an accolade she cherishes – and has been awarded the MBE.

Sheila Stewart continues to thrive on people and life and her singing and story telling are still best experienced in the flesh. Her rich voice, singing unaccompanied, redolent of the countryside, is like a full-throated songbird. It carries history and tradition and connects us to a time when we lived close to nature and respected its gifts and dangers. In that listening moment, time is suspended in the presence of our shared humanity and in appreciation of our world. This reader is grateful to her for her gift of this life and its story. If you have not heard her live then this book will make you want to hear that astonishing voice sing its conyach [heart music] – it really should have an accompanying CD!