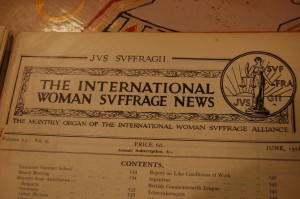

This month, GWL celebrates International Archives Day (9th June). Yi Wen, one of our volunteers, explores Jus Suffragii, the International Women’s Suffrage Newsletter.

Jus Suffragii, or The International Woman Suffrage News was published by an organisation called The International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA). The Alliance began in 1902 in Washington, United States of America when a group of leading suffragists from 11 countries met and decided to form an organisation. This organisation was envisaged as a central bureau to collect, exchange and disseminate information on suffrage work

internationally. The IWSA was constituted in Berlin in 1904; its periodical, Jus Suffragii, began in 1906, and the Alliance met regularly until the outbreak of war in 1914. The group continued its operations throughout the First World War, and by the end of 1920 the IWSA had affiliated societies in 30 countries throughout the world, with its headquarters in London.

It is the internationalism of Jus Suffragii and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance that marks them out as unique. For this organisation, the international sisterhood and the women’s cause overrode nationalist loyalties – war itself was seen as a cause to be defeated in order to further the development of democracy worldwide. This cross-cultural dimension gave Jus Suffragii a distinctly pacifist voice, and encouraged the idea of a positive dialogue between women that transcended national boundaries. One example of this occurred in 1915 when IWSA members from different countries, including those at war, met to found IWSA’s sister organisation, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. The Open Christmas Letters, exchanged between English and German feminists between 1914-15, also encapsulates this anti-war sentiment. Despite its broad reach, individuals in the IWSA could remain active in the organisation without relinquishing their sense of a separate and unique national identity.

One of the issues facing Jus Suffragii in its quest for an international appeal was language. Published mainly in English and French, there was an undoubtedly Euro-centric focus to its writings and appeal. Although in 1932 the editorial staff proudly announced that language would be no obstacle to the publication of news submitted from different countries, the same article also declared that the printers of the journal could handle only roman alphabets! The newsletter also had a tendency to present a patronizing and at times negative view of non-European cultures, though this imperialist rhetoric also asserted a bond of vulnerability uniting women across the continents.

When leafing through the Jus Suffragii collection held at GWL, which covers the years 1918 to 1938 , what really struck me about the newsletter was its vision and ambition. It does have some shortcomings, but overall it is inspiring to see the efforts of early 20th century women’s rights campaigners from across the world brought together in one publication. Given the way in which air travel and the development of the internet have effectively shortened the distances between us today, it can be easy to overlook the remarkable work that must have gone into maintaining an international women’s network without these modern tools. Jus Suffragiiis a wonderful testament to the dedication and purpose of the women whose hard-fought campaigns helped win the liberties we enjoy today. It provides a fascinating glimpse into the history of women’s movements across the world, and reminds us of the continuing need to campaign on behalf of women who still lack the most basic freedoms and rights elsewhere, as well as in our own countries.