by Kelly Ann Cecillia McGhee

—

For the last few months, Kelly has been volunteering in the archive researching materials relating to the introduction of Section 28 by the Conservative Government in the 1980s. Before embarking on looking at these materials, Kelly had not heard of Section 28. Through looking through the letters; campaign materials; posters and other bits of ephemera related to the introduction of Section 28 and the campaigns resisting it, Kelly has put together a picture of the law and its wider implications for Lesbian and Gay individuals and communities until its eventual repeal in Scotland in 2000, and England and Wales in 2003.

—

What was Section 28?

In 1986, Clause 28 (known more commonly as Section 28) was introduced by David Wiltshire, a Conservative MP. This bill prohibited local authorities from: ‘intentionally promoting sexuality or publish[ing] material with the intention of promoting homosexuality.’ It also went on to declare under this legislation that local authorities shall not promote: ‘the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.’

Effectively, the Conservative Government at the time had introduced legislation which encouraged overt discrimination against the lesbian and gay community, as well as bisexual and transgender people as well. This affected many areas within society mainly education and family life, however it is important to note that it also had a wider impact too, particularly on the public perceptions of LGBT people.

The Labour and Liberal parties attempted to make amendments to the bill but were defeated within the House of Commons. Many Labour MP’s attempted to change the legislation and Lord Willis proposed a complete ban of the bill. This however, did not occur and the clause came into effect in April and was in force by June 1988.

The wording of the Clause caused much confusion as it used the word ‘promote’ suggesting that a person who in the eyes of the state saw homosexuality as acceptable could potentially be punished for voicing this in a library or school. This meant that those in the education sector such as schools and colleges were prohibited to provide their pupils with important information on sexual education. In consequence, educational institutions were legally obliged to view homosexuality negatively and with bias under Clause 28. Pupils who experienced prejudice were unable to voice the discrimination that they faced, and little counselling or support was available to families or children. Moreover certain books were also prohibited from classrooms, teachers were also unable to disclose their sexuality in fear of losing their jobs and teachers and parents were no longer in control of what sexual education their pupils or children received.

Clause 28 called for greater government control over the educational curriculum and also parental rights. The government openly proposed to take control of education from the local authorities, from schools and teachers and from parents.

The Effect of Section 28

Much of the media also managed to raise hostility against homosexuals over issues such as AIDS/HIV. Politicians, the media and even parts of the church were used as powerful tools to define social attitudes towards homosexuality and gay and lesbian people. Using rhetoric about the safety of children as well as drawing dangerous comparisons between homosexuality and criminal behaviour was common.

MPs fed this rhetoric by questioning relationships between gay people and children. In a Commons debate of Section 28, one Conservative MP for example is quoted as stating:

“Children under two have had access to gay and lesbian books in the Lambeth play centres.”i

The same MP also said:

“Has my right honourable friend noted the recent report that infant teachers in Haringey are somehow using home office funds to produce videos promoting homosexuality, and terrorism in South Africa?”ii

Most of the myths that took place at this time were escalated by the Government who first imposed the bill and the tabloid press who also played a part in dividing people and spreading fear. One myth was that the local authorities who were against the clause would in effect, indoctrinate children and encourage left wing policies. Many press articles, found in the archives at GWL, present these kinds of allegations as facts.

The Fight Against Section 28

Thankfully, there were some strong courageous voices which campaigned relentlessly to counteract these narratives and end the discrimination which Section 28 encouraged. These are minutes taken by the ‘Stop the Clause Campaign Education Group’ who wrote down actions and connections in the hope of eliminating this prejudiced clause:

Stop the Clause Campaign Education Group

The clause proposed (1988) will make it unlawful to ‘promote’ homosexuality.

Goals

- To make connections of opposition to the clause teachers, parents, staff, etc

- Connect with equality within education organisations

- Highlight the negative impact on pupils and the community

- The vulnerability of gay parents as well as children as a result of Clause 28

- What the legal term ‘pretended’ and the damaging effects this has on family life when it is seen legally as a ‘pretended relationship.’

- Representing gay/lesbian couples as illegal. Prejudice will not be considered harmful; this will affect both adults and children

- Clause 28 is the only instance of controlling children’s education.

- Stressing that equality within the curriculum of education is not a contradiction but an effortiii

Similarly an article in The Guardian explored how the ways in which Clause 28 affected the meaning of equality.

“In reality the undefined image of the term ‘promotion’ will open the door to continuous legal challenges to any work by the local authorities to adopt non-discriminatory policies, support counselling and advice services or counter misinformation towards homosexual women and men. Clause 28 will if it becomes law prevent any council from responding to needs of its lesbian and gay men in council employment and in the delivery of services. We believe the clause is an attack on equality of opportunity for homosexuals; its implications, threaten us all.”iv

The Effect of Section 28 on Culture

Many campaigners were afraid that the clause would have an impact on cultural services such as libraries, museums and theatre. In one piece of campaign material by the Stop the Clause Education group, there is a suggestion that the law implies that potentially works by artists like Michelangelo of Leonardo Da Vinci could disappear from public life.

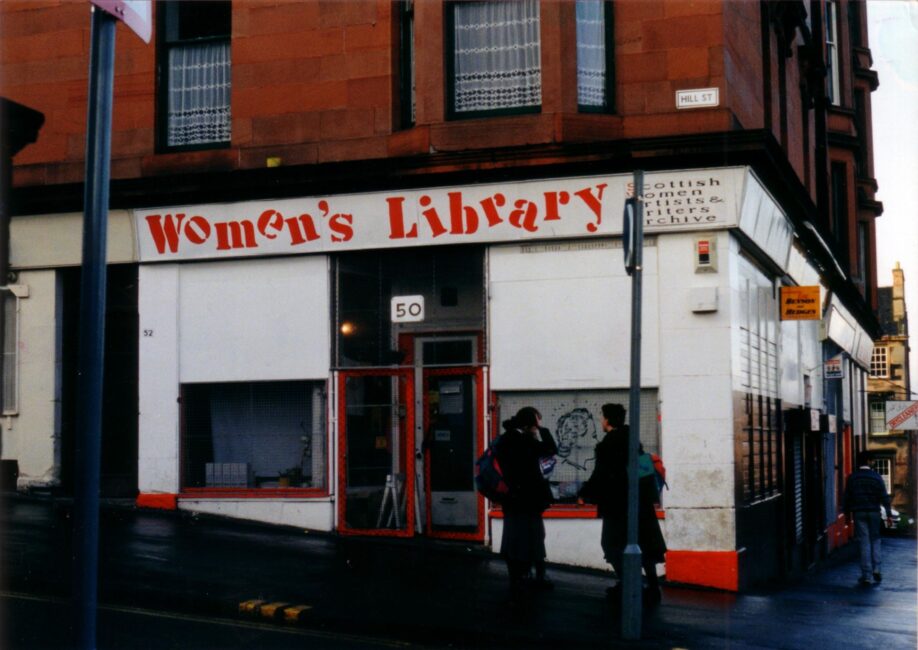

The censorship of books and reading material deemed as ‘promoting homosexuality’ was common. There were thousands of books that represented heterosexuality positively but far fewer books which explored homosexuality in a positive light. Public libraries felt increasingly under pressure to remove all homosexual content from their shelves, putting copies of books and LGBT press behind the counter and or ‘out of sight’ of children. This meant that literature that could have supported those who felt isolated and confused about their feelings was hidden from view, an act which undoubtedly led to increased levels of social isolation for many LGBT people.

The Effect of the Clause on Families

The law also had a major impact on family relationships, particularly where children were concerned. The law presented gay family as being impossible (stating that local authorities, and schools in particular, should not promote “the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”). This had a major impact on support services for children and families, and undoubtedly impacted on the ability of gay families to access social services or adoption services.

Many gay/lesbian parents suffered under this legislation. One such mother said that when she went to court to get an order to keep her violent husband away she realised how skewed the system was. She explained that when she said she was a lesbian in court, they concentrated on her and became less concerned with her husband’s violence.

“It was amazing how all the men in the court, whatever their age or their position, were united against lesbianism. My husband and the judge were on the same side.”v

This same woman was also accused of feminising her son. She learned that these were standard accusations in court against lesbian mothers, fuelling the anti-man myth. Her husband’s violence was seen as justified and she was also banned from having any contact with her lover.

Jill Butler, a lawyer, voiced concerns about the Clause and the effect it had at the time on lesbian mothers.

“I think undoubtedly anything which contributes to a climate of bigotry will hinder lesbians from getting custody. Anything which singles out a minority also legitimises prejudice. It is a dangerous law.”vi

Throughout this research, it is easy to see the catastrophic consequences that enforcing a law against a group in society can have. It is also surprising to see how many areas within a community it influenced. It is impossible not to admire the strength of the campaigners: not only did they campaign for the equal rights of LGBT individuals but for every single one of us. Through direct action (for example invading the BBC News Studio during live broadcast or abseiling into the House of Lords) and tireless information gathering and research, the campaigners against the clause tirelessly fought a law based on prejudice and state censorship. Without the backlash against Section 28 it’s easy to see how the rights of others, not just LGBT people, might have been further eroded in such a comprehensive way through government legislation. Throughout history, inequality has brought about deplorable events, it is therefore important to look into the past and think retrospectively as it allows us to see what more needs to be done in the future. Thankfully, the Clause was abolished in Scotland in 2000 and 2003 in the rest of the UK. At this moment in time, there is still a need for more education on discrimination in schools; I propose that the subject Section 28 should become a part of the curriculum as it highlights the issues around inequality.

i) Jill Knight quoted in Section 28: A Guide for Schools (Draft), Stop the Clause Education Group, June 1988

ii) Jill Knight quoted in Section 28: A Guide for Schools (Draft), Stop the Clause Education Group, June 1988

iii) Stop the Clause Education Group Flyer, c. 1987, Section 28 LAIC Subject File

iv) Clause 28: Why it Poses a Threat to Everyone, Press clipping from the Guardian, date and issue not listed, Section 28 LAIC Subject File

v) The Guardian, April 25, 1988, Section 28 LAIC Subject File

vi) The Guardian, April 25, 1988 Section 28 LAIC Subject File

—

Return to We Recruit!: Campaigns and Organisations or the LGBTQ Collections Online Resource.

—