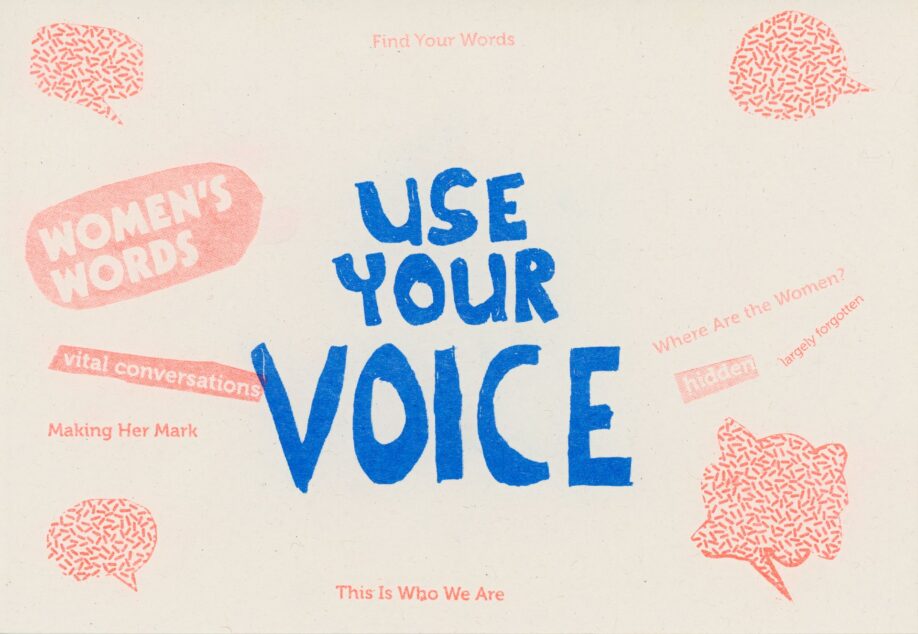

Our 2024 Bold Types Scottish Women’s Creative Writing Competition marked the twelfth year of Scotland’s first free creative writing competition for women and we received loads of incredible short stories and poems in response to the theme of HOPE.

Our shortlisted writers read their work at our online Bold Types Creative Writing Showcase on Thursday 21st November in front of our wonderfully supportive and encouraging panel of judges: Karen Campbell, the award-winning writer of eight novels and creative writing teacher; Titilayo Farukuoye, winner of the 2022 Edwin Morgan Poetry Award and co-director of the Scottish BPOC Writers’ Network; and GWL’s own librarian, Wendy Kirk

The panel had a tough time deliberating but we’re delighted to announce that the winners of our Bold Types: Scottish Women’s Creative Writing Competition 2024 are Tara Jackson and Aileen Angsutorn. Tara was the winner of our short story category with Caracoles and Aileen took the top spot in the poetry category with the poem Buteo Buteo – A Coupling. Congratulations to Tara and Aileen and to all of the other women who were bold and entered our competition.

We are happy to share a selection of shortlisted poems and short stories below.

Caracoles by Tara Jackson

Daddy got me searching for snails.

Caracoles, he calls them. He can’t say it right. It’s all gooey and round in his mouth. He can’t say it like me and mamma. I got mamma’s tongue.

Snails know how to fear my wriggly fingers like they know how to fear sun. I go finding them in dark rotting places. They suck green guck on the rocks. They climb on the moss covering daddy’s wood pile. Those logs aren’t fit for burning no more. Our house is cold in winter now.

Beneath those logs they be hiding. I find a whole yummy bunch. I find them squirming under there, where the grass can’t find no light to grow itself, and they be eating all that rotting wood, and they be filled with it until they fat and juicy and good for eating.

I pinch the shell of their squirmy wee bodies until I got in my hands two squishy piles. I bring them inside to daddy and he be so happy.

Caracoles. He keep on saying it and I don’t say a word cause his face be so happy. He cook them garlicky and buttery the way I like it. Daddy put an extra plop of butter on my plate. I don’t say a word, just scoop them out their steaming golden pool. All the little bodies are wrinkled now, like old men curled up in bed. I bite and chew and juice squeezes out their bodies and makes little bubbles in the corner of my mouth.

Daddy say they don’t taste like mamma’s. I don’t remember mamma’s.

After dinner I scrub the shells. Inside becomes shiny and smooth. A pearl tunnel leading somewhere I can’t fit. Outside becomes beautiful big swirly brown. They shells be looking like mamma’s face in the stars.

I keep them in her old jewellery box, where all her rings and fiddly-bits go. I try closing the lid and all them shells come pouring out. All them swirly brown shells are whizzing across the floor like big meteors up there in space. I’m afraid I’ll step on one and make it crunch. That’s when daddy see me and say I can’t keep them no more. He say some beautiful things just got to be tossed back to earth. He say another crawly creature will come and make its home in there and I got a home as it is.

Now he speaks every day in mamma’s tongue. Caracoles. But I say it better. Caracoles. I got a home. Caracoles. I want to crawl up inside it. Caracoles. I want to curl up there. Caracoles. Twist round the bends. CA-RA-CO-LES. I be finding a nice swirly slimy home in there. Right down deep and dark where I won’t come slipping out. No one ever be finding me.

The Otters by Gill Ryan

The island is so quiet I can hear a single willow leaf drop onto the still surface of the river and set off slowly towards the sea. A slight movement of wind and a whole flurry of leaves join it on its autumn journey. I am the only person on this wee island in the Tay. On the other side of the river is the big town that calls itself a city, but on this side I can hop across the stones when the water level is low and be completely alone.

I hadn’t planned on being alone. I’d come in the hope of spotting the Tay otters, or at least signs of them. But there is no trace of their spraint, no otter prints in the mud, no splashing in the water. I am seemingly destined to be the only person in Perth who has never witnessed them.

This isn’t the first time they’ve eluded me. A long-planned trip to Skye last year, armed with binoculars, turned up no otters either. We visited hides at dusk, their most playful time, and all was completely still. We spent a day at a bay that famously had otters swarming along the beach and cheekily visiting nearby back gardens. We sat and we waited until our sandwiches were eaten and the tea in our flask was cold, but the swarms did not materialise. Fair enough, otters can’t be expected to perform to accommodate my holiday timetable.

We came back from Skye to stories of sightings on the Tay, to friends’ videos of blurry bobbing heads in the river, and newspaper articles with close-up photos of furry little faces. In Scots the otter is known as a dratsie, which is close enough to the sound I made as I watched those videos. Fine otters, if that’s the way you want to play.

Gaelic has two words, beist-dubh (black beast) for the sea otter and dòbhran (water dog) for the river otter. Dòbhranach means abounding in otters but I’ve never had occasion to use that adjective. There are tales in Scottish folklore of King Otters, bigger than the average otter, with magic skin, and the power of granting wishes if captured. That’s not my plan for them at all, though if wishes were going the world is certainly in need of them just now.

I admit I was drawn in by images of family groups linking each other as they sleep on the water so no one drifts off. Of mammy otters floating on their backs while cuddling baby otters on their bellies. And otters called Steve with their own social media accounts. I know, the reality is not always so cute. Their scent up close is more of a stink. Sea otters live up to the name of beist and are known to do nasty things to baby seals and even carcasses. Don’t google it. The only time I’ve seen them (in captivity), they were fighting viciously.

And yet, I’d love to see one in the wild. I visit the highlands and islands when I can and always take my binoculars because you never know. I venture out hopefully to local river islands at low tide. I’ve seen shy red squirrels, leaping hares and flashes of kingfisher in the beautiful Scottish countryside, but no otters. I’m beginning to suspect I have displeased a King Otter in some way and he has ordered them to hide from me.

What more can I do to attract otters into my life? If manifestation worked I’d have seen them by now. I have otter prints on my wall, an otter pin on my jacket, books about otters on my shelves. I receive otter-themed cards on my birthday. Himself suggests I get an otter tattoo, but on my back so I never actually see it.

I sit on the island and choose to enjoy the stillness and the late September sun on my skin. I let my mind drift to the places in the world that are being devastated by war and appreciate what an enormous privilege this peace is. I think of the forests that are burning across the globe, but in my pocket of Scotland I am surrounded by greenery. If only I could share this. I breathe deeply and choose gratitude for what I have, letting go of the longing for what I haven’t.

A splash disturbs my contemplation and the longing is on me again. I race as quietly as I can to the source of the sound, peering through brambles and scrubby trees with their feet in the water. A dark shape is floating a few metres away. Heart pounding, I grab the binoculars from my bag. This is it.

It’s a log. A broken branch has fallen into the water and is now joining the leaves as they sail down the Tay. Somewhere in the undergrowth, I’m convinced, a King Otter is mocking me.

Hope by Ruth Reid

Apple Pie by Philippa Ramsden

“To plant a garden is to believe in tomorrow”

Audrey Hepburn

To plant

an apple pip,

is to hope,

to trust

that tomorrow’s

tomorrow

will bring,

a freshly baked

apple pie,

crusty with

caramelised sugar,

plump apple flesh

sending aroma-puffs

of apple-cinnamon scent

inviting the whole street

to make custard.

Hope by Carolyn Sleith

Whit’s th’ maist hopeful animal? is it th’ dove? is it folk? na it’s th’ heid louse. Bear wi’ me….

Head louses…head lice…can only bide in ae place. On a human heid. They cannae bide on ither parts o’ the human, ‘cause they need hair o’ a particular diameter tae cling tae. They need firmer hair follicles tae hide fae nitcombs in. They need the warmth o’ our bodies or they’ll be deid. They need our blood tae feed. They cannae eat anything else. Only human blood. They cannae fly, they cannae jump, they can only crawl. An’ they only live for 33 days in total an’ can only survive 48 hours away fae a head.

So how do they spread, eh? They cannae be passed on by pets since they only live oan humans. Because they need warmth an’ blood, they cannae last long on clothes, hats, or pillows either. All the books say they need tae crawl fae one hair shaft on one host tae another. How often do we sit wi’ our hair tangled up wi’ some ither person’s? Naw, never. I’ve never believed a word o’ this nonsense about bairns sittin’ close thegither an’ passin’ on lice that way. It just doesnae seem plausible.

An’ if ye gie yer wean a hug, the louse wid need tae be bionic tae crawl frae ae hair on the wee yin’s heid tae anither on yours.

Head lice are actually the bravest o’ wee beasties. They crawl aff their lovely warm, nutritious heid intae furtniture an’ clothes an’ hope those items’ll lead them tae anither fresh heid.

On the subway, a mature louse will gather the gumption to leave the safety of a bonnie heid, crawl onto the seat, and hide in the pile, hoping that some other long-haired laddie or lassie will plunk themselves down on the chair so they can make their way to a new heid. They’re countin’ on the hustle and bustle of city life and the need for us to wear clobber. They have to pray that another human bein’ shows up within 48 hours, or they’ll be facing the end.

Aw no’ a’ the heid lice are that adventurous, though. Some o’ them need tae bide on the heid tae breed an’ reproduce, causin’ a right irritatin’ infestation. But some, when they hit aboot 17 days auld, are fully mature adults. At this point, if ye’re a female heid louse, it’s probably in yer best interest tae mate, so ye can move on tae a new heid ready tae lay yer eggs. So, I reckon the pregnant females are the most hopeful an’ adventurous, ye ken? It doesnae make much sense for an adult male tae leave the heid. If they leave, they’re lookin’ tae find a new mate an’ a new heid tae reproduce.

Essentially, fae a survival o’ the species point o’ view, it aye makes sense if the mated females leave the safety and sanctity o’ the heid. A lassie has tae gather her nerve, once mated, tae crawl fae the hair shaft intae the great unknown. The hat, the jumper, or the train upholstery. Hoo does she decide tae dae this? Wi’ blind bit o’ hope and optimism. She feels the pull tae seek oot new pastures. A heid wi’ lang hair tae cling tae, braw blood tae drink, and warmth for her eggs.

If she manages tae make it tae a new head, an’ we ken she does sometimes, ’cause we’ve aw had tae endure the fine-tooth combing tae clear the nits an’ lice frae our hair at some point or anither. If she makes it, then she’s got juist 16 days left tae lay aboot 6 eggs a day afore she keels it. So there’s likely tae be between 64 an’ 128 eggs laid by oor adventurous maw. She’ll live lang enough tae see the first eggs she lays hatch intae nymphs, but she winnae see them grow tae full adulthood afore she dies o’ auld age.

She left her home whaur things were bountiful an’ warm, an’ it was a guid place tae raise a wee family, an’ launched hersel’ intae the great unknown tae raise a family on a strange heid, wi’ nae chance o’ ever seein’ her weans grow up an’ nae chance o’ seein’ her grandbairns. No juist that, but her colourisation was adapted tae the heid she was born oan, sae if she’s a vastly different colour frae the hair on the new heid, there’s a much higher chance she’ll be noticed oan the new heid. That’s a risk. She might be a brunette louse on a blonde heid, drawing attention every time she moves.

She haes tae hope that some o her dochter’s (haein mated wi her sons) will hae the courage tae crawl aff the heid too or they’ll be fated tae try an live as lang as they can on the heid an die in the toxic Excedrin or be wrenched fae safety by ‘the comb’.

In aw honesty, it’s a miracle that heid lice survive at aw an continue tae spread aboot the community. Because tae the best o my knowledge, heid lice are still a public health issue and heid lice are no endangered. Unlike the pubic louse wha’ve suffered destruction o their habitat and may weel be endangered as a result.

So the next time ye feel like ye cannae go oan and life seems hopeless, remember that an insect the size o’ a grain o’ rice, pregnant like, took her life and those o’ aboot 100 o’ her wee bairns in her claws, and left her safe world, crawled intae the abyss tae reach another planet tae preserve her kin. And if that’s no bravery and hope, I dinnae ken what is.