In my last blog I detailed a visit to Norway to visit Vanessa Baird, I would like to expand that now to share something about the rest of my visit, which involved being hosted by Oslo Art Weekend as well as a visit to Katie Paterson’s Future Library, housed in the new central library in Oslo, and to the Office for Contemporary Art, who sent me away with lots of amazing books on art to add to our library collection.

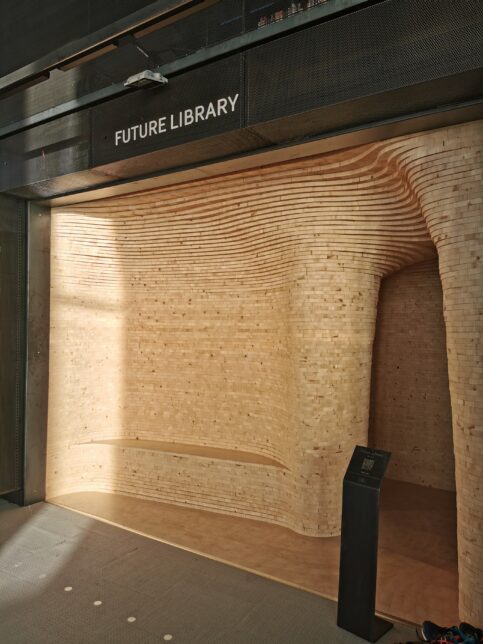

The central library, opposite the concert hall, is truly well used and inspiring take on what a library can be and mean to the city’s population. As a library worker this was an essential and heartening visit. The building, free to use and open to all, is furnished with a combination of practical considerations and luxury, and it feels like the city has responded to that with each space well used and by a really diverse group of people. On the top floor of that building is Katie Paterson’s conceptual art piece the Future Library, a small, sauna like room designed to hold 100 manuscripts of books commissioned and written now that will be made in 100 years from a specially cared for forest on the outskirts of Oslo. I will say more about this artwork later on but for now just to say it was a beautiful and contemplative space to visit.

Ida Marie Ellinggard who curated Vanessa Baird’s show in OSL did an amazing job connecting me to the vibrant contemporary art scene in Oslo and despite being a last minute addition the team running the Oslo Art Weekend (brilliantly hosted by festival the Director Silja Leifsdóttir and co-ordinator Martina Petrelli) gave me a huge warm welcome, including me on a tour with a number of other ‘critics’ from all over the region and further afield. Being included in this meant there was more to see than I could ever hope to cram into the few days I had for my visit. Also more than I can write about in detail so I will focus on my highlights here including Camille Henrot’s Mouth to Mouth preview at the new Munch Museum, The stunning Niki de Saint Phalle retrospective at The Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, a fascinating tour with artist Brittany Nelson of her show Meet Me At Infinity at Fotogalleriet and a moving performance and installation Skiver for å ikke skade by Marthe Ramm Fortun on the streets and within the art space Femtenesse. Besides previews I was hosted at social events where I was able to meet artists working locally in Oslo and could start to understand the art ecology there as well as the history of some of the spaces.

Our first visit as part of the art weekender was to Fotogalleriet for the opening of Brittany Nelson’s Meet Me at Infinity. When the exhibition catalogue opened by referencing one of my favourite science fiction writers, Ursula Le Guin, attempting to write about ‘a genderless or less gendered planet’ and about ‘the ridiculousness of people in power in the present’ and finally Nelson’s queerness, ‘not succumbing to what is expected by society’, I knew this was an exhibition that despite being a lonely and strange offer would be right at home in GWL as well as here in Fotogalleriet. Meet Me at Infinity centres the perspective of the mars rover robot, ‘Opportunity’, presenting a number of monumental bromoil prints made by Nelson and selected from a catalogue of images taken by the rover, who despite being given a life expectancy of 90 days, survived 15 years on Mars. Seeing these strangely romantic images, blown up and shaped by Nelson in a process that involved many hours working without a break and driving around to dry the huge prints in her station wagon, I felt in awe of how she negotiated this huge archive of images creating something new, somewhere between fiction and reality. The Mars photo prints were accompanied by another archive, a series of holograms made by Nelson from letters written by James Tiptree Jr, the pen name for a woman called Alice Sheldon, detailing all the women who had rejected her in her lifetime. In the exhibition Nelson appeared as a kind of poet and voyeur (aren’t we all voyeurs in the archive?) of the archive, projecting alternative queer histories into the present moment as if from a distance future. The care taken around Nelson’s haunting subjects is conveyed in good measure by her technical artistry, which painstakingly transforms the materials and feels healing, as if through these transformations we’re invited to be with these alienated subjects, as time collapses on itself rendering them less alone.

After Fotogalleriet we walked to Femtensesse, a gallery founded in 2020 by Jenny Kinge, in an old building transformed into a winding artist studio complex. On the website they mention ‘an experimental approach to exhibition format’ and Martha Ramm Fortun’s performance in public space with installation in one of the small rooms of the complex seemed to fit that bill. In a different way to Nelson her performance was an engagement with history, linking events like the impending sexual consent law to debates about sexual morality from the 1880s and her own body in public space. We followed Ramm Fortun out of the complex and across a busy road, over a roundabout towards a fountain, this act of moving in an unusual way together created bonds in the audience which Martha later seemed to strengthen, reaching out to people in moments that evoked a sense of solidarity in an otherwise angry and urgent performance. She read from a script, that I was unable to understand, but also moved beyond it in extreme ways, climbing over a fence to lie in a pool formed at the edge of a waterfall. Where language fails (in this case my languages, but I think also more generally her performance did push at the borders of what can be said in words) I thought about waterways, unconsciousness ancient movements through the city that connect us.

The next day we travelled to the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter a large art centre with a collection of over 8000 works and sculpture park, a little outside of Olso, built to house Sonja Henie (Figure skater, Hollywood actress, business woman and Norwegian icon) and her husband Niels Onstad’s art collection. We were there to visit the Niki Saint Phalle retrospective. Niki Saint Phalle is an artist whose work I had seen before and whose aesthetic has made an indelible mark on how we remember the look and feel of the 1960s without her really getting the credit or attention she was due (a phenomenon we’re quite familiar with at GWL). In the first galleries there was rage again (picking up from last night’s performance?) with the space echoing with gunshots from a small video clip of Saint Phalle shooting paint targets in her early explosive ‘shoot pieces’, surrounded by compelling range of plaster cast sculptures holding together a mismatch of pop culture, religious and military items moulded into new forms ranging from abandoned brides to a rampaging T-rex. The curator Caroline Ugelstad explained that they had played with the light conditions in these first spaces keeping them dark to emphasise the mood of her early works before we walked into the lighter, euphoric spaces playing host to her later works which depict the joy and freedom of imagined matriarchal utopias, full of rounded female figures, primary colours and giant theme park designs and installations. Quite apart from the amazing breadth and depth of work the show was an example of impactful exhibition design complimented by the permanent exhibition that followed it of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Room Hymn of Life which guaranteed if you came in angry you went out singing.

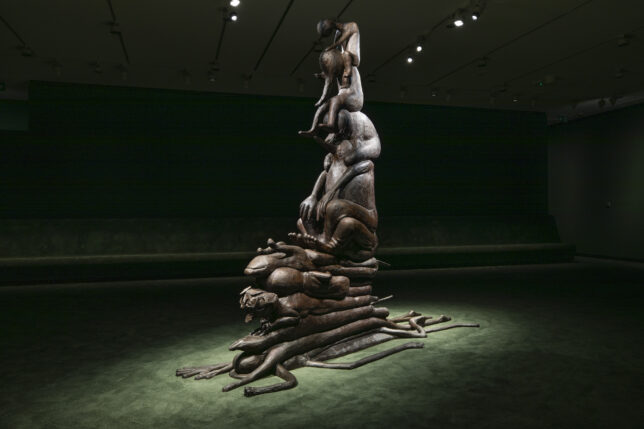

In the afternoon we were treated to a look into Camille Henrot’s exhibition Mouth to Mouth at the new Munch Museum. What I knew of this brand new iconic Museum in the heart of the city was that it had caused some controversy. The desire for a monumental building had led planners to choose a tower like structure that would break the skyline of more modest, homely buildings (that follow the Nordic logic that lower structures let more light in, casting smaller shadows) that otherwise characterise the city. I had I wondered what they would do with that extra height – the initial answer is an exhibition by Camille Henrot who was awarded the Edvard Munch art award in 2015, giving her the first guest show in the museum. The exhibition like the architecture is about how we negotiate relationships, opening with a look into those first ones between an infant and their caregiver. These early intimacies are not idyllic scenes, in a mess of moving red watercolours, it’s hard to see where the lines are drawn between one figure and another, instead it’s a system of attachment (this is also the title of the series) that involves encroachment, tiredness and guarded feelings. Beyond the opening series the exhibition also contains two other parts, Code of Conduct which draws early etiquette books (the type of Do’s and Don’ts manual that we also have in our archive at GWL) with internet screen grabs. These works were in stark contrast to the first series evoking the mismatch between our blurred human interactions and memories and the impersonal folders on a hard drive designed to contain them. The final room in the show consisted of the monumental bronze sculpture Family of Men on an extremely lush green carpet in a dark room. Curator Tominga O’Donnell writes that Camile Henrot’s Family of Men (who are look like strange and comical creatures to me) ‘shuns the soaring and even sentimental verticality and appear to be regretting the whole venture’ – I can’t help but wonder what this means given the architecture it was made to be placed in?

I want to end my sprawling blog with the mention of a second library visit (by way of returning to where I started on my favourite subject of libraries). Housed in one of the last places I visited, the Kunsthall Oslo was the Assata library, self-titled as ‘an activist library celebrating revolutionaries of the global majority’. I was really glad we were able to stop here and chat to one of the organisers, Neslihan Ramzi, who related a story that felt familiar to our own history at GWL. They explained that the library was currently nomadic and had been created to provide visions of the world by creatives and writing that they had not been exposed to in the art and education systems they had experienced. Seminal texts by writers of colour with important things to say. The library, provided a space for us to rest on a tour of really excellent exhibitions, but it also offered critique by way of being perhaps the only intersectional voice in an offer that was otherwise hearteningly full of feminism.

The contemplative space and vision offered by Assata brought my thoughts back to Future Library in the other space in the city that enabled me to see the diversity of Olso’s population. I haven’t spoken much about the amazing group of writers and creatives I met through being hosted on the tour but I’d like to mention one curator from Iceland, Þórhildur Tinna Sigurðardóttir, who is a collaborator on the Icelandic Art Center podcast Out There. Chatting to Tinna I realised I could listen to Katie Paterson speaking about Future Library with Icelandic writer Andri Snær Magnason on the podcast. In this episode Katie and Andri speak about the concept of ‘pancake sci-fi’ the aim of which is to move sci-fi away from visioning futures that we feel alienated from, gadget heavy Blade Runner style realities that are so far from our lived experience that we can’t hold them in our hands. Instead they talked about time (thinking of 100 years as relational amount of time in which children can touch the voices of their grandparents) as something within our imaginative reach. This idea of time, rooted in now but also just beyond our lifespan offered the hope that some things in the future would remain the same. Katie mentioned the hope of a still being able to stand in a forest in 100 years and of still eating pancakes around a kitchen table with our grandparents. Listening to them I thought of the importance of representation in our visions of the future, of things we recognise. I thought of Brittany’s Mars Rover allowing us to see ourselves in apparently alien landscapes and what these glimpses of something familiar, provided by all these artists in different ways, mean for our ability to really create the changes we need to see in the world.

Details of the excellent Assata Library catalogue can be found at: https://assata.no/

You can listen to the Out There Podcast with Katie Paterson here: https://icelandicartcenter.is/out-there-podcast-episode-5-andri-snaer-magnason-in-conversation-with-katie-paterson/