In this week’s blog we hear from Chloe Spence, a Speaking Out project volunteer who has been working on developing the project exhibition which will open at the Museum of Edinburgh in November.

I have been volunteering with Women’s Aid on the Speaking Out project for about a month now, attending workshops on selecting archival materials, selecting oral history extracts and exhibition design. Exhibition assistants were divided into pairs and allocated a theme to focus on. I was looking specifically at services provided by Women’s Aid, with primary subtopics of ‘Refuges’, ‘Children’ and ‘What is Domestic Abuse?’.

While I am still no expert, I do feel like I have learnt a lot since the beginning of the project – most shockingly about the complex and multifaceted nature of domestic abuse, but also – on a more positive note – about the work of Women’s Aid, the strong ethos underlying the organisation and all they have already achieved.

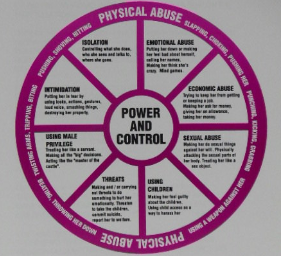

The complexity of abuse was captured well by an image my pair encountered in one of the workshops: the ‘Domestic Abuse Wheel’, attributed to a Women’s Aid local group newsletter from the 1990s. Each spoke of the wheel represented one common component of abuse – for example, the use of intimidation, isolation and economic abuse. On the outside of the wheel were the more obvious, stereotypical manifestations of abuse: violence, physical or sexual. At the centre were power and control.

Domestic abuse is not about weak individuals but about persistent manipulation and degradation, shaping relationships that are often built on both dependency and fear. This can make it incredibly difficult for an outsider to understand – as encapsulated by, for example, a description by one of the interviewed former refuge volunteers, who spoke of one woman who had been utterly terrified of her own husband but fiercely confronted the husband of another abused woman when he appeared at the refuge. From outside of the situation, however empathetic we are, it is impossible to ever fully understand. It is because of this that Women’s Aid’s ethos of empowerment, and respect for women’s own perceptions and decisions, is so crucial.

Obstacles aside, over the years Women’s Aid have made brilliant efforts to be thorough, considerate and collaborative in their services. As well as providing shelter and safety, early refuges provided abused women with a safe space to share their experiences and emotions, and to gain support, sympathy and validation (including from women with very similar experiences to theirs). For many women, this was the first time they voiced their experiences of abuse. Groups evolved over time to provide more support and advice, not having anticipated the crucial role that this would play in many women’s recovery.

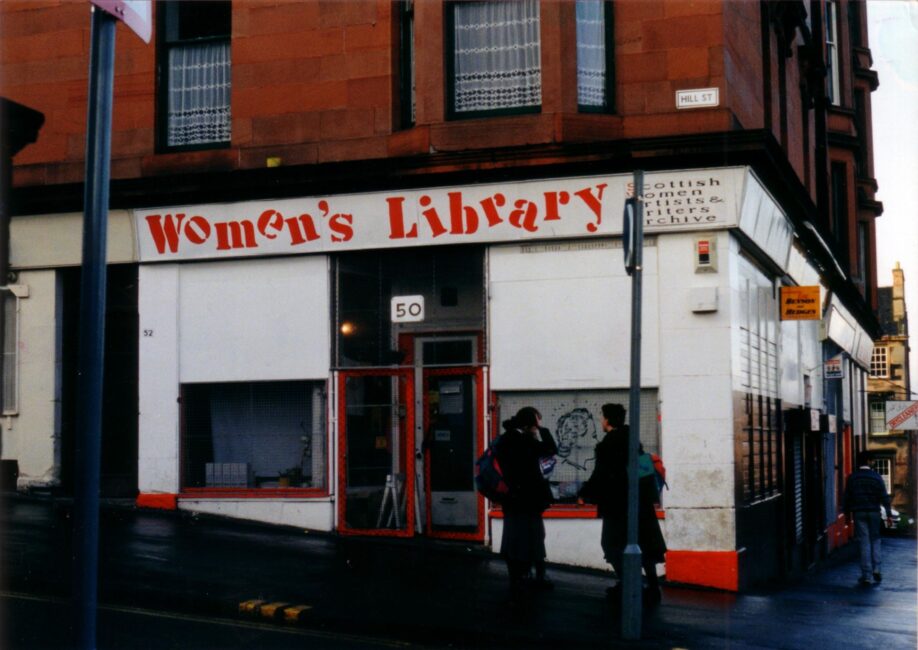

Looking at old pictures, what was striking about the refuges was that for the most part they looked just like ordinary houses – both inside and out. While this was partially to stop women’s abusers from locating them, there was a definite impression of ‘homeliness’ in some of the photographs and artistic representations, highlighting the importance of mutual support between the women. Between the years of 1979 and 1994, Women’s Aid also ran Culdion Housing Association, providing communal housing for women and children leaving refuges. At the same time as starting to take control of their own lives, women were helping and inspiring other women, building up support networks that often made it easier for them to resist returning to the abuse.

Since 1982, when the first National Children’s Worker was appointed, Women’s Aid has also worked directly with children – who are often overlooked in domestic abuse cases, yet have a profound set of needs of their own, and may also be used as pawns by the abuser. Interviewees commented on the importance of viewing children as individual agents, and of maintaining or rebuilding positive relationships between mothers and their children. Presumably with this in mind, Women’s Aid has more recently run projects such as Cedar (Children experiencing domestic abuse recovery), during which both mothers and children attend groups to explore their emotions.

Undoubtedly, society still has a long way to go; for as long as Women’s Aid is necessary, there will still be more to be done. Nonetheless, over the past 40 years, Women’s Aid has helped countless women to leave abuse behind and rebuild their lives – and, still today, continue to work towards a safer, happier future for women and children across the country.