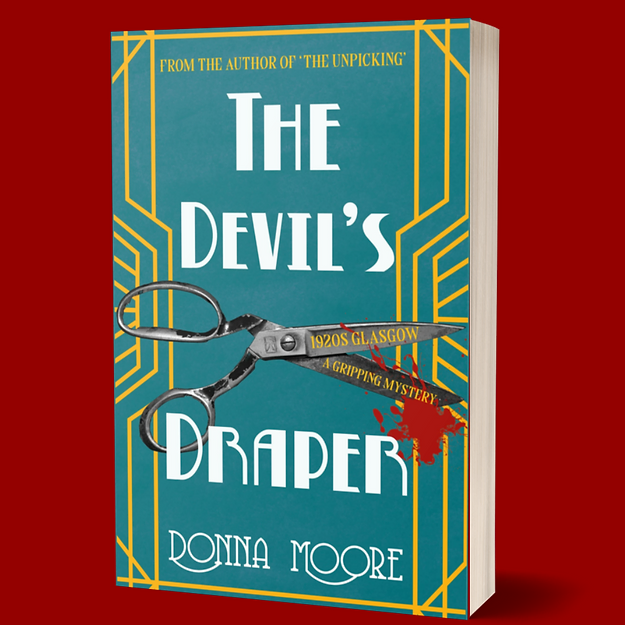

Anabel reviews Sisters of the Bruce by J. M. Harvey

Anyone who knows anything about Scottish history will be familiar with the Story of Robert the Bruce and his struggles to unite Scotland under his kingship – but many will not know that he had five sisters. Through the eyes of these women, J.M. Harvey’s novel retells the history of the 20 or so years leading up to Bruce’s victory over the English at Bannockburn.

The story opens in the family home, Turnberry Castle. The Bruces’ mother has just died and life is about to change for all of them – but the five boys, including Robert, will have far more control over their own fate than the girls will. The oldest, Isabel (Isa) is soon despatched to Norway to marry its King, and she sees out the rest of the story in relative safety. Not so the other sisters who suffer because of their brother’s decisions.

Over the years, Robert’s battles make his sisters’ the targets of his enemies. The youngest two, Mathilda and Margaret, escape to Orkney but Christina (Kirsty) and Mary are captured. Kirsty, having already lost two husbands, is separated from her children and incarcerated, under harsh conditions, in an English nunnery. Mary’s fate is even more brutal – for several years, she lives suspended in a cage from the walls of Roxburgh Castle. Eventually, after Bannockburn, the women are freed but their lives have been shattered for ever.

The book is told partly as a narrative and partly through letters between the sisters. It’s not an easy read – the author has done a huge amount of research, which is commendable, but sometimes her desire to fit it all in makes it seem more like a textbook than a novel. However, you do get a very clear picture of the barbaric practices of the time, the difficulties of life for everyone, and the particular problems of being a woman and therefore subservient. Mary is bitter towards her brother for “taking the Scots crown as his own, placing them all in such jeopardy.” Mathilda, as part of peace negotiations, is forced to marry the son of a bitter enemy: “How could Robert ask such a thing? How could he make peace with a man who had caused them all such pain?” Even Isa, safe in Norway, moans in one of her letters that “It seems to me that women are so often alone and in charge, adeptly overseeing great estates and large households, but when the menfolk return, we must become servile again.” Bringing the hidden history of such women to the forefront is exactly what Glasgow Women’s Library is all about, and this is a weighty contribution to that aim.