Not long ago, I was waiting in the queue for drinks while out with friends. I was happily minding my own business when suddenly I felt someone pinching my behind. I turned around to discover two young guys, giggling away to themselves and denying they had done anything. Irritated, I tried to simply ignore them and order my drink. As soon as I turned away, the cycle continued, right in the middle of a really crowded bar – and nobody did anything. I eventually stomped on the man’s foot as hard as I could. He left me alone after that, but not before shouting at me that I was ‘crazy’, to ‘calm down’ and that it was ‘nothing serious’.

Not long ago, I was waiting in the queue for drinks while out with friends. I was happily minding my own business when suddenly I felt someone pinching my behind. I turned around to discover two young guys, giggling away to themselves and denying they had done anything. Irritated, I tried to simply ignore them and order my drink. As soon as I turned away, the cycle continued, right in the middle of a really crowded bar – and nobody did anything. I eventually stomped on the man’s foot as hard as I could. He left me alone after that, but not before shouting at me that I was ‘crazy’, to ‘calm down’ and that it was ‘nothing serious’.

Why am I starting this review with an anecdote, I hear you ask? It’s because any woman reading this will easily be able to recall countless similar experiences they’ve had to endure – moments where they’ve been demeaned and their protests have been met with a simple ‘stop complaining, you’re making a mountain out of a molehill’. Being leered at on the street, ‘dumb women’ jokes… Is it acceptable? Of course not.

Laura Bates’ disapproval of such statements went viral through the Twitter handle @EverydaySexism. Through the Everyday Sexism project she received over 50,000 stories of discrimination suffered by woman across age ranges, lifestyles and countries, and she has now collated these experiences into a book of the same name.

In this account, Bates cites newspapers, current affairs and research to show some truly depressing facts about the world we live in today: the UK is 57th in the world for gender equality in parliament, girls as young as 5 are becoming obsessed with their image, nearly 70% of female university students have experienced some form of harassment…One particularly alarming example is a study wherein identical CVs were sent to universities – the only difference being whether the name at the top was male or female. The ‘men’ were offered the job more frequently and at a higher rate of pay. What struck me when reading these examples over and over again is how open people are about this discrimination, the way they find it not just acceptable but amusing. US radio host Rush Limbaugh, criticising a woman who argued that contraceptives should be free, jeered, ‘If we are going to pay for your contraceptives, and thus pay for you to have sex, we want something for it, and I’ll tell you what it is. We want you to post the videos online so we can all watch.’ When reading nonsense like this, it’s hard to believe we’re in 2014.

Bates intersperses these public incidents with anecdotes taken from the Everyday Sexism project, and this is where the book really shines. These experiences are not reworded but instead quoted exactly, giving every tale both a different tone and a ring of authenticity. She organises the chapters by category (education, the workplace, violence against women) and also includes a section collecting men’s thoughts and how they encounter sexism as an everyday occurrence, something I really appreciated and, indeed, hadn’t properly considered.

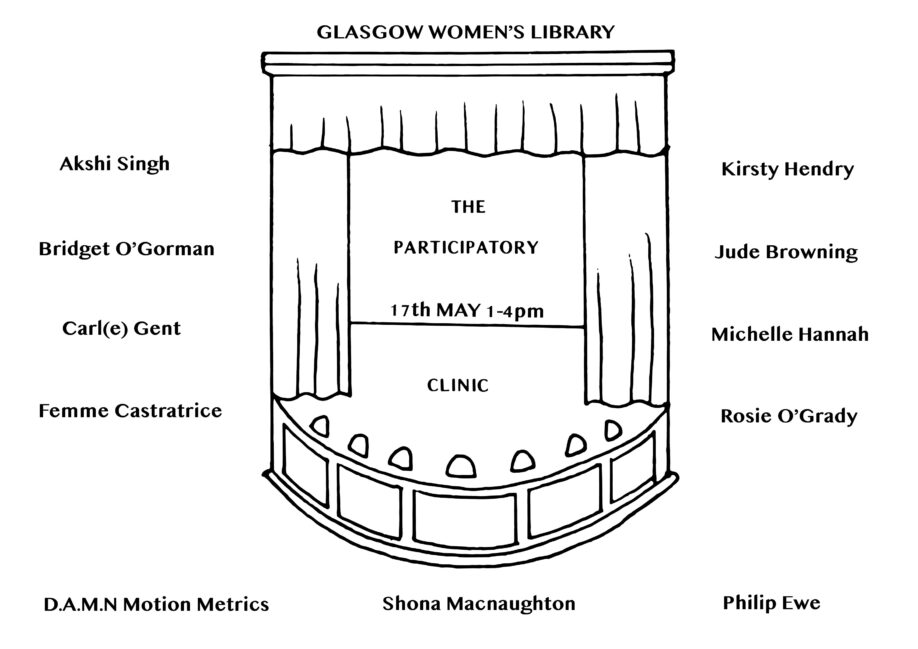

Bates does not provide any real answers regarding turning the tide against this wave of sexism – she does mention one account of forcing Facebook to change its rules on pictures through protest, but there are no notes of advice. However, Everyday Sexism seeks to prove to people that the problem exists, and we all need to change our thinking in order to move forward. When viewed in this light, the Women’s Library’s status as a safe haven becomes even more important.