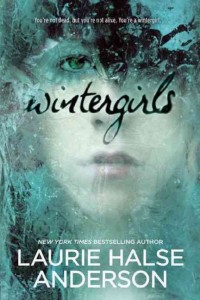

Wintergirls drew me in because I have already read other works by its author, Laurie Halse Anderson. Her most famous novel is Speak (now also available as an excellent film starring Kristen Stewart), a narrative detailing the turmoil of a girl who, after being raped by a popular boy at school, withdraws socially and privately. As this summary suggests, Anderson has no problem tackling difficult or harrowing subjects; Wintergirls is no exception.

Wintergirls drew me in because I have already read other works by its author, Laurie Halse Anderson. Her most famous novel is Speak (now also available as an excellent film starring Kristen Stewart), a narrative detailing the turmoil of a girl who, after being raped by a popular boy at school, withdraws socially and privately. As this summary suggests, Anderson has no problem tackling difficult or harrowing subjects; Wintergirls is no exception.

The book tells the story of Lia, a previously hospitalised anorexia patient who appears to be improving – outwardly, at least. However, within her own thoughts, we discover that this is a mere façade. Cassie, another anorexia sufferer and Lia’s former best friend, has been found dead alone in a hotel room after trying to call Lia 33 times, throwing Lia’s life into further disarray. Cassie’s death, Lia’s guilt and her status as a ‘wintergirl’ – someone who is half-living, half-dead – make up the main conflict of the narrative.

What is most striking about the novel is Anderson’s almost visceral prose. Mantras are repeated for pages on end, Lia’s true thoughts are scored out constantly, and a variety of fonts are used when Lia is trying to regain control of her thoughts. Some people argue that this is a gimmick or Anderson simply trying to be ‘modern’, but these moments show the split between Lia’s personality and the image she projects to the world around her, something everyone can empathise with. Additionally, Anderson doesn’t gloss over any of the harsh realities of anorexia. Lia’s monologue gradually seems to collapse in upon itself and becomes increasingly claustrophobic as she loses her sense of control (hinted at by constant calorie counts of food). It should also be mentioned that this is not a book for younger children or those who are easily upset, as pain and self-harm are described in graphic detail.

Anderson gives us a further image of a fractured family: divorced parents who, while well-meaning, do not have enough time for their child, a step-mother who doesn’t seem to have much of an impact on Lia’s ways, and Emma, Lia’s half sister and the real sense of joy and hope in the novel. The happiest moments in the book are the loving reactions between the two sisters.

However, I do have some slight criticisms. Without wishing to spoil too much, I would say that the book falls down on its ending: it felt clichéd and, as I turned the last page of the book, I felt slightly cheated. In addition, Anderson’s characters are not as well fleshed-out as they are in Speak.

Wintergirls is at times an uncomfortable read. However, this is ultimately its strength. It functions on an educational level, dispelling the myths about anorexia and portraying its true dangers. While I don’t think it quite reaches the heights of Speak, Wintergirls is still an accomplished work.