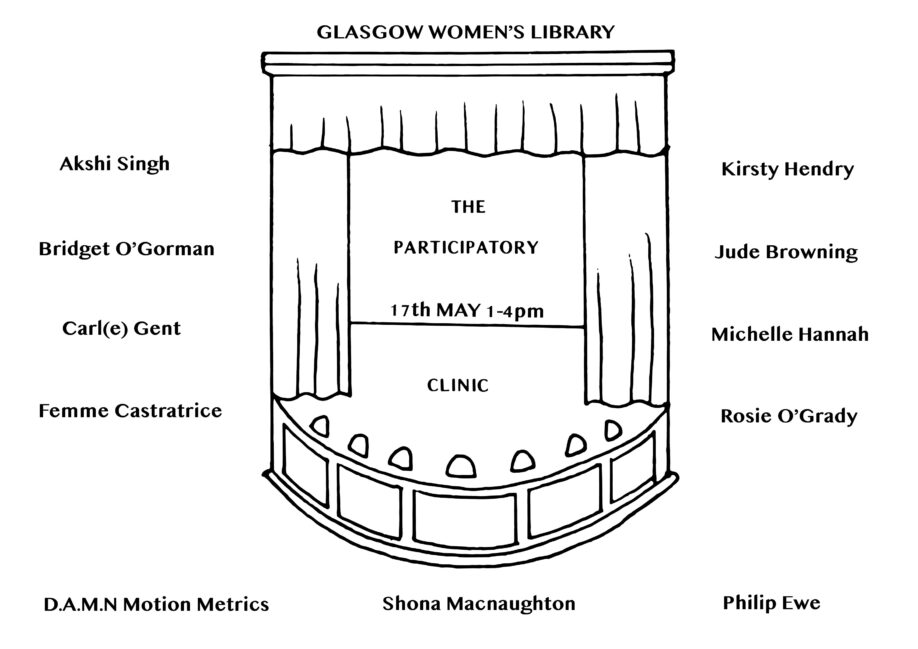

Adele Patrick participated in the Subject in Process symposium at the CCA on Saturday, 6th September 2009.

With film screenings including D.A. Pennebaker’s ‘Town Bloody Hall’ and work by contemporary filmmakers exploring issues of gender, the day involved a surveying of the connections between art production and feminism.

Discussions were wide-ranging and involved an examination of the curatorial issues surrounding the display of work by Eva Hesse at the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, and an exploration of the current and ongoing issues concerning equality and representation at the Transmission Gallery, Glasgow. Sam Ainsley, Sarah Lowndes and Adele Patrick examined aspects of the histories and legacies of feminism, art and activism in Glasgow.

More information about the Subject in Process symposium can be found at the CCA website.

Making space for women: a review of the work of Women in Profile and Glasgow Women’s Library, 1988-2009

Paper delivered by Dr. Adele Patrick, Lifelong Learning and Creative Development Manager, Glasgow Women’s Library, at the Subject in Process symposium, CCA, Saturday 6th September.

The ‘Subject in Process’ symposium seeks to ask if artists could be considered to have an obligation to connect with events in the real world.

In 2010 Glasgow Women’s Library will relocate to the Mitchell Library and this presentation will reflect on the specific significance of a ‘women’s library’ in the civic, cultural and historical landscape of Glasgow.

Introduction

I have been asked to address a key question of this symposium, namely ‘Can artists be considered to have an obligation to connect with events in the real world?’

I would like to offer a response using two ways of thinking about the role of the Women’s Library in Glasgow. These two perspectives germinated for me in 2007; the first during a seminar series entitled ‘Working in Public’ that involved representatives of Scottish arts projects and practitioners in a discussion surrounding the work of the American feminist artist Suzanne Lacy.

Lacy’s participation in the seminars was a form of public interrogation of her practice, specifically her work in Oakland over 20 years. At some point during the discussions I began to reflect on my own engagement over the same period with Women in Profile, the group that gave rise to the Glasgow Women’s Library and the Library itself as a form of ‘working in public’ or artworking with communities that could now be examined and reflected on in a longitudinal way.

Glasgow Women’s Library has been variously critiqued as not a real Library, not a real artwork or artspace, as not living in the real world (principally for focussing on women and not men). What I hope to illustrate is that despite or because of this liminal, unsettling and indeterminate status GWL has been open to and uniquely positioned to develop work that responds to the heterogeneity of women’s experiences from different worlds often using the agency of art and artists.

Women In Profile

The group of women who gave rise to Women in Profile, (mobilised around the announcement in the late 1980s that Glasgow was to be European City of Culture in 1990) were largely women trained in the Visual Arts. Like many of the more positive stories about women and art in Glasgow in the last couple of decades Sam Ainsley was at the root.

Sam was invited to attend an early meeting of dissident women based at Glasgow University who were rallying to prevent an all white all male roster of talent being drawn up for the 1990 Festival programme. Unable to attend she suggested my name. The group grew into a project to be called Women In Profile that established a less than modest base in Dalhousie Lane.

Their work culminated in a programme of women’s art and culture during September 1990.

Two earlier women’s arts gatherings in Glasgow had academic links and concerns but Women in Profile had an early schism that had forged it into a project at a remove from the academy and open to and reflective of community engagement.

The festival in 1990 was indicative of the hybridity that has characterised the future Women’s Library and its anomalous positioning straddling academic and real world concerns, exploring issues of hidden histories, representation and women’s access to cultural capital.

It seemed to many of us a resonant and timely activity taking place as it did coincident with the excavations that were unearthing the Glasgow Girls (women working in Glasgow in the arts and crafts from 1880-1920) from obscurity.

The Women in Profile programme included Castlemilk Womanhouse, a project referencing feminist art precursors in California and Leeds in the early and late seventies. Whereas the germinal Womanhouse had been staged by arts undergraduates in a 17 room mansion in Hollywood, Womanhouse Castlemilk involved artists working in and with a community of women.

Other memorable landmarks of the programme included a history of Glasgow Women’s Aid curated by artist Susan Montford, Hertake, a festival of women’s film at the GFT, and the first and as far as I know the only an exhibition of Women’s Art at Glasgow School of Art,

The origins of Glasgow Women’s Library

Post-1990, and inspired by visits to Women Artists Slide Library, London and exchange visits to the Kunstlerinnerarchiv then in Nuremberg, Glasgow Women’s Library was launched in Garnethill in 1991 by the ‘survivors’ of the 1990 Festival. Significantly, it was women’s arts collections rather than for example the Fawcett Library, now the Women’s Library, London (part of Guildhall University), that were catalysts.

The origination of a Women’s Library in Glasgow, the first and only resource of its kind in Scotland grew from an impulse to capture and preserve the records generated during the Women in Profile period and (somewhat naively) to start to collect and make a space for other diverse records of women lives and histories in Glasgow and beyond.

We learnt more about the women’s library and museum movement in the first few years by visiting mainly arts libraries and archives in Europe through our links with IAWA, an international network of women artists groups that had held their conference in Glasgow to coincide with our festival. One, Das Verbegene Museum (the Hidden Museum) in Berlin, had been established to show work by women hidden in the storerooms of major museums in Germany.

Subsequently, and after a move to premises in Trongate, the broader network of global women’s libraries opened up to us through the KnowHow project, a group of over 400 women’s libraries from over 140 countries. Attending Knowhow gatherings in Amsterdam in 1998 and in Mexico in 2006, GWL workers gained a clearer perspective of its role and context both locally and globally.

Significantly, this is a network that is not Euro- or US-centric but built on feminist principles of inclusion. At the last Knowhow conference in Mexico only one of the 100 plus organisations attending was from the US and the network is dominated by South and Central American, African and South Asian resources. There are currently 6 women’s libraries in Ecuador and libraries in Benin, Angola and Iran.

Through these connections we discovered both the specificities of our own project and the distinctness of our sister organisations. Each was reflecting in their collections and activities the particularities of locations and engagements with women locally or nationally that had shaped their histories and development.

Countering the homogeneity of mainstream libraries and library systems; these women’s libraries appeared reflect the lives of the women involved.

GWL forged connections and shared ideas with women’s libraries as distinct as the august Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College, Harvard and the Mumbai based, women’s library, Akshara. In India alone there are 16 women’s libraries each with its own specific address to women. For example, SPARROW (the sound and picture archives for research on women) also in Mumbai preserves cultural objects connected with women’s lives and has built a largely non text based collection that women who are not readers can use and contribute to including oral histories, songs, photographs, cartoons, posters, drawings, and other audio-visual materials.

From feminist librarianship we have gradually learnt more about our role as guardians of women’s culture. Feminist scholarship in this area has centred on the gendered critique of the monolithic, patriarchal structuring of knowledge developed by Melvil Dewey, introduced in 1876 and currently used in over 200,000 libraries worldwide.

Perversely, none of the Glasgow women’s library founders were librarians, fortunately, this enabled the collection (all of which is donated) to grow oblivious to the hegemonic impact of Dewey. ‘Women’ as a category only made it into the 21st edition of Dewey in the 1970s due to the impact of feminism and feminist librarianship.

Only when we had amassed over 20,000 volumes over more than 10 years were we able to recruit our first librarian. The librarian could by that time access the fruits of feminist librarianship and has consequently evolved a specific feminist informed classification system.

This classifying of items in the collection strikes me as an evocative scientific/artistic endeavour. In our use of models from Japanese, Indian and European women’s thesaurus collectives (the latter allows for regional and local idiosyncrasies and for flux in the interpretation of language information and knowledge) a feminist classification system has been coined for what now is the largest collection of information on women in Scotland.

Crossing Boundaries

Lacy has reflected on the ways in which her practice necessitated an ongoing engagement with micro and macro political and social structures.

In order for the women’s library to survive and develop a meaningful practice negotiations, interventions and partnerships have had to be created, bridging and traversing discrete territories and cultures including the communities of women in Glasgow and the Visual Arts, Libraries, Archives and Museums sectors.

On reflection, and learning from Lacy’s model, I now acknowledge how an education as a visual artist facilitated my own specific strategies of engagement; shifting registers in order to work with local and national groups and politicians and officials, voluntary sector organisations including those working with women in crisis, with academics, archivists, librarians and of course other artists, architects and designers.

Who uses GWL?

GWL has developed into a genuinely broad constituency of users where the worlds women inhabit are present. Its current cohorts of learners and project users include around 60 women a week who attend English classes, women who are developing their literacy skills, women from a range of ethnic minority backgrounds, many of whom work on specific projects exploring issues of identity and ethnicity. These women’s use of the Library involves them working alongside and coming across women academics, researchers, artists and those involved in radical practices who may of course also be one of the above.

GWL differs from mainstream public libraries in that it grew from the grass roots, it was a library that was wanted and needed by a community of women and its collection is composed of and reflects the diverse interests of its users.

In 2007 the Library moved for the third time. At this critical stage we felt that it was important to record the memories and experiences of women users and employed two artists to work with women in our community to record their histories of engagement and the physical space of the Library.

Filmmaker Jan Nimmo and photographer Rachel Thibbotumunwe created documentary records and portraits of library users and also trained staff, volunteers and learners to use film and photography to make their own records. This is an ongoing and expanded process.

What is apparent in these records from the Documenting 109 project is the way women defy easy categorisation, they represent only themselves and their reasons for using GWL and choices of favourite texts from the Libraries collection are idiosyncratic, whether Whoopi Goldberg’s autobiography, a 14 year old’s essay on the suffragettes, zines, or catalogues of Czech women artists’ work.

Cultural Planning

Moving onto my second point of reference for the conclusion of this paper, I want to take up a strand of ideas around the geographic and political specificity of GWL. I began to think more about this through my research on Cultural Planning begun in 2007.

Cultural Planning is a relatively new approach to thinking about cities that has given rise to the notion that ‘others’ including artists, driven by economic necessity consistently form a nucleus of activity in geographic areas that through the processes of regeneration and gentrification become the desirable arts, tourism and residential quarters – the processes that are taking place in Harlem now and that took place in SoHo in the 1980s, the process that took place in the Merchant City, the former centre of the rag trade in Glasgow, and is taking place now in Trongate.

Cultural planners point to the risk of ennui and entropy that can infest the regenerated quarter when the real, the communities that surround the area are not at the helm of this process. This ennui is something that Francis McKee has indicted in his criticism of the post-makeover CCA. From a cultural planning perspective one might ask how were the local communities of Garnethill, especially BME communities, involved in this specific regenerative process. And now, sadly, a similar post-mortem is required of The Lighthouse project. Cultural Planning critiques the industry of regeneration that has spawned identikit bridges, giant wheels and armadillos not to mention national and local departments, officers and policies, whilst failing to adequately engage and consult, invest in, empower and seed the generative quarters where ‘others’ live and work.

Cultural Planning theorists have sought to critique and ameliorate the blight of regeneration ennui, the homogeneity of urban shopping streets and the showboating typified by the proliferation of icons of regeneration in the unfortunately still moribund Clydeside by advocating steps to approach working with people.

Sadly the Cultural Planning theorists have, like the regeneration czars, failed to fully engage with the potential of rigorous embedding of gender politics but in essence I feel that this approach to working with communities is an antidote to both the endemic global homogenisation of the regenerated city and locally the perpetual modelling and remodelling of a masculinised incarnations of Glasgow.

Using Cultural Planning methods gave me a new approach to seeing how GWL has attempted to both generate a locus for a resistant form of activity and community led regeneration and created and sustained the possibilities for feminist interventions into an uber-masculinised city.

A Cultural Planning approach posits that in order to create positive change in environments a community must first be critically mapped by those who live in it and who want change. “[an] audit of possibilities based on exploring the distinctive cultural assets of a place.” (Ghilardi, 2005)

GWL’s evolution has been driven not by political priorities but through the expressed needs of women and their own articulations on and critical mapping of Glasgow.

In the Library space and in the other locations we have worked with women who have spoken about: not seeing themselves reflected in the city confronting male violence in the streets and at home, that they are not heard or consulted and that they feel inadequately served or respected as citizens.

These testimonies reprise the histories of women’s lives eclipsed by the masculine mythologies that are still very much in evidence; yesterday I heard on Radio 4 that Peter Capaldi will explore Scottish art, which was lazily summarised in the trail as a survey of ‘Glasgow Boys Old and New’.

Far from the conditions of women’s lives improving, (and a women’s project like a women’s library becoming an anachronism in the face of a post-feminist resolution of gendered issues) since 1990 the gains of feminism are in jeopardy as the short-lived and relatively toothless Women’s Committees have been dismantled.

Rahder and Atilia note that the political class have “neutralised the debates on gender in an all too rapid bid to homogenise ‘otherness’ where gender is typically subsumed subsumed within the discourse on ‘diversity’. Thus the transformative element of gender politics is diffused.” (Rahder and Altilia, 2004)

In a context where gender inequalities have been increasingly masked or ‘disappeared’ we try in our work with women to use as a starting point the clear instances of gender inequality in Glasgow for example:

- There are only three statues of women in Glasgow. Only one is Glaswegian and she paid for the monument herself.

- 142 people had been given the Freedom of the City since 1800: 6 were women, two of whom were non-royals and only one was a Glaswegian woman. (Subsequently, in partnership with Amnesty International, GWL campaigned successfully to have Aung San Suu Kyi awarded the Freedom of the City of Glasgow.)

- One in five women in Glasgow can expect to experience domestic abuse at some stage in her life. (88% of crimes and offences of domestic abuse and 95% of crimes of indecency (mostly sexual assault) are perpetrated by men against women in Scotland.)

However, a more rigorous mapping with gender awareness of the kind required for Cultural Planning, for example, How many girls are fearful of walking in their local park? How may women attend exhibitions in their neighbourhood? etc, are elusive due to the lack of gender sensitive information and gender disaggregated data.

And this is something that I hope arts institutions, for example those about to inhabit the regenerated Trongate 103, will seek to address.

Although in literature in theatre and art women have made inroads this has failed to ignite the imagination of the guardians of culture for the possibilities it opens up to address the lamentable aspirations of many young women. In a recent visit to Govan High School, of the 30+ young women we worked with none could remember the last time they had studied a woman in any subject.

In 2007 volunteers involved in the Women Make History project at GWL decided to start to literally map historical sources on women in specific geographic areas of Glasgow. In the early stages of the research we discovered that of the two official Glasgow City Council’s city walks, published on their websites, neither contain information on women. We are now working with the Friends of the Glasgow Necropolis to address this.

Fired by this discovery the group decided to research and script the first women’s heritage walks of Glasgow. This activity has grown into a core project in GWL’s Lifelong Learning programme involving women as tour guides, researchers and campaigners.

From its grass roots origins GWL without revenue funding and in the face of post-feminism now employs 12 staff and will move next year to the Mitchell Library where it will have its own space whilst maintaining its charitable status.

The work of Women Make History has given rise to 4 women’s heritage walks that have begun to reconfigure the map of the city to include women’s histories and lives. In the spring we will begin to train women and women’s groups nationally on unearthing women’s history to create a network of women’s heritage walks across Scotland as part of a Scottish Government funded National Lifelong learning programme. We are now members of museums, galleries Scotland and are seeking accreditation as a national resource and have a lifelong learning programme that works with over a thousand women learners a year.

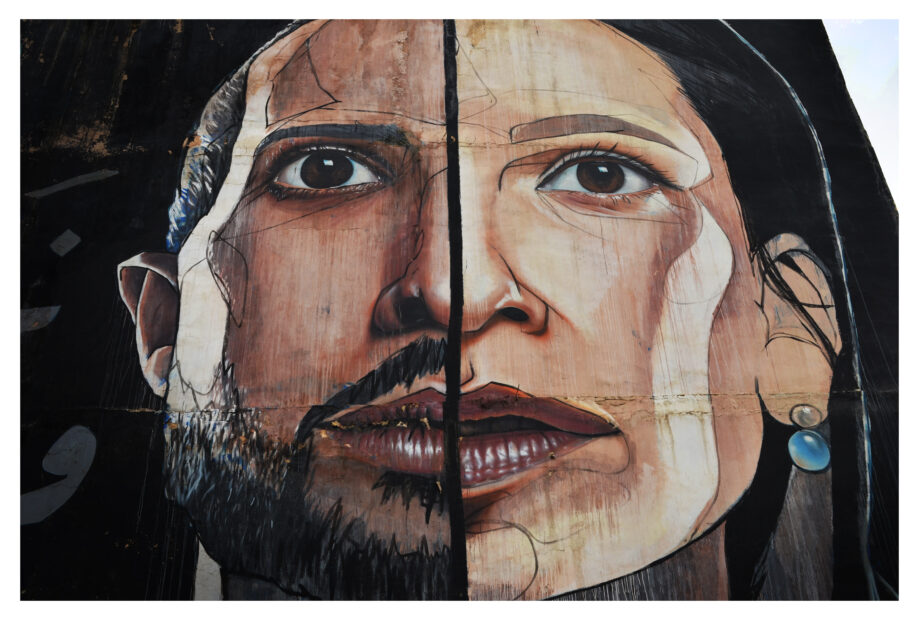

Last week we recruited two artists to work on the first phase of an SAC funded Public Art project ‘Making Space’ which will culminate in a brief for a new public artwork marking women’s history and lives outside our new premises at the Mitchell.

Charles Landry, the leading voice of Cultural Planning, posits a model where in the most significant urban interventions, this approach has enabled a reversal of fortunes for the ‘branding’ of cities. Derry, a byword for political and cultural conflict and divided communities was, through the agency of a ‘culturally planned’ rethink, enabled to became a renowned centre for Conflict Resolution. (Landry, 2000)

Acknowledging the cultural legacy of Glasgow as the masculine (the ‘mean’) city, the home of the Glasgow Boys et al. GWL’s work posits the question: Can Glasgow be reconfigured as the city that becomes synonymous with upholding and promoting the diverse cultures and histories of women alongside its legacy of positive contributions to culture by men? This has been the purpose of GWL and we hope this ‘Making Space’, the latest episode in our work with women and women artists, will make this manifest in the real physical landscape of Glasgow.

© Adele Patrick 2009

Unless otherwise stated, all images are © Glasgow Women’s Library